Is AI Art Net Art?

Video & prepared remarks for the symposium with Vladan Joler, Valentina Tanni & Eryk Salvaggio examining the transformation and consolidation of the Web from the 1990s up to the age of generative AI.

Is AI Art Net Art?

As someone who writes critically about AI, I often get asked why I engage with it at all. In response, I would say that "AI" — as apparatus, as politics, as data extraction, as epistemology — is engaging with me already. My practice is about making distance by making space.

That's the stance at the heart of an adversarial AI practice. It isn't about collaboration, because I don't have a choice in the matter. My data will be analyzed, my picture taken at the stoplight, the tools integrated into the university or the workplace.

I don't collaborate in my artistic practice with AI. I try to antagonize – and analyze – back. It's been at the heart of my technology based practice since I started out, as a net artist, as a teenager. I wasn't coding per se, as in, I wasn't developing websites or building platforms. I was making-with the materials of html and javascript, ASCII characters and browsers, while resisting and inverting their logic.

In the friction, I cultivated a way of understanding the web. I saw it as a medium of communication. But to communicate, you had to do certain things according to certain protocols. The browser constrained you, but you could find unusual parts of the network.

You could use the source code to make additional layers of the work. You could reimagine autoloading html pages as a slow motion projector, imagine ASCII characters as a means of transmitting video, as in this 2002 piece, RGB.

Eryk Salvaggio, RGB (2002), which used auto-refreshing HTML and ASCII art to create an interactive video stream. Originally a browser-based artwork.

Looking at the basic building blocks of the web as code and text, I was drawn to ASCII art — in which text characters operated as shaded pixels. This style of work is challenging to archive — there were glitching browser behaviors that animated the work, which owes a lot to the glitch-net-art pioneers JODI and ASCII artist Vuk Ćosić, which don't work anymore, so even these videos are not quite right.

Eryk Salvaggio, Lambs in Ascension (200X), which used a browser-based glitch and ASCII art to create an animation. Originally a browser-based artwork.

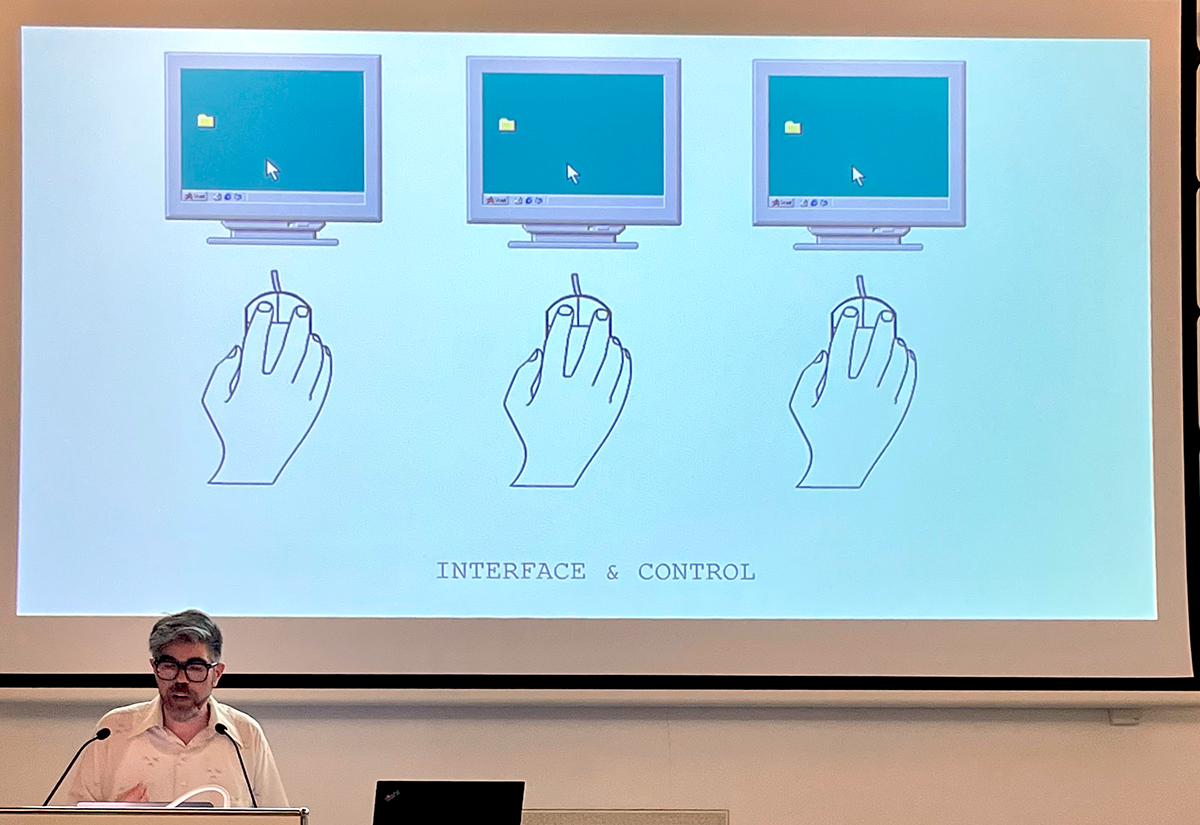

In other works, such as Lambs in Ascension, these animations took over the browser. The idea was twofold: to reveal, immediately, that the user's sense of control over the browser was an illusion steered by the interface, and an attempt to get into that protocol and disrupt it. The corporate takeover of the web, the control of web hosts and servers, was not a foregone conclusion. There were other ways of arranging the net, and other ways to visualize and imagine it.

Companies grabbed larger and larger portions of audience share, and the rest is the story of the Web we have today. The platform hospitality of the Web became its primary illusion, and its protocols became even more complex and inaccessible.

Auction Stand for Personal Hate

Part of any successful Net Art practice was being kicked off of a platform for unexpected behavior.

For example, in 2001 I used eBay to auction off a profound personal hatred toward whomever paid the most for it. I got up to $50,000 before eBay canceled the auction and introduced a clause that objects sold had to have a material form. So I tried to sell a drawing of my hate, which you see here; they canceled that too, with no explanations.

In a recent publication, "Cultural Red Teaming: ARRG! and the Creative Misuse of AI Systems," published in Critical AI, co-authored with Caroline Sinders and Steph Maj Swanson, we discuss the role of creative misuse in AI art, an idea that comes, from a few paths, through the legacy of net art.

Anna Watkins-Fisher's 2020 book, "At Play in the System: The Art of Parasitical Resistance," put into words something that I had struggled to identify in my own practice. It examined internet art acts, like mine with eBay, as a new form of aesthetic resistance that aims to navigate our own entanglement with capitalist logics of power. Not by resisting or refusing them, but by using them incorrectly, to do things they were not intended to do.

Jon Ippolito described a strategy among net artists back in a 2002 article in Leonardo, "10 Myths of Internet Art," in which he distinguishes "innovation" from art-making in net.art:

"What sets art apart from other technological endeavors is not the innovative use of technology, but a creative misuse of it. To use a tool as it was intended, whether a screwdriver or spreadsheet, is simply to fulfill its potential. By misusing that tool–that is, by peeling off its ideological wrapper and applying it to a purpose or effect that was not its maker's intention–artists can exploit a technology's hidden potential in an intelligent and revelatory way."

But this innovation can also backfire, as Watkins-Fisher writes:

"What are the meaning and value of a politics of disruption when artworks that are critical of corporations and government institutions can be said to help them—however inadvertently—close their loopholes? When hackers actually help states and corporations improve the security of their information systems?"

Parasitical resistance relies on this hospitality, siphoning resources from the host – the platforms – in ways that create beneficial outcomes to the world beyond the host. It means coming up to the borders of that hospitality in ways that reveal its limits, showing the degree of control and the expectations of normal behavior that are demanded in return.

The spaces for creating glitches online, either through bad code or weird behaviors, were understood on these platforms as errors. When engineers had more time and motivation, these spaces artists had found and exploited would be fixed. The noise in the channel would be eliminated, and the system would be "better," in the sense of usability and purpose – typically, data collection, marketing – in ways that ultimately limited the scope of actions afforded to the user.

Fixing the AI Glitch

As we turn to AI, this relationship is as timely as ever. The glitch in AI reveals something just as radical as the glitch in the browser and just as vulnerable to recuperation. It shows us that the system is choreographed toward certain sets of illusions.

AI is an industry driven by a proliferation of illusions: sustaining myths that depend upon loose definitions of intelligence, decision-making, reason, and creativity, while paradoxically emphasizing new forms of control for the people who use them. AI is simultaneously a thinking being and nothing more than a tool: a personal, exploitable employee to propel all of us into new levels of wealth and disconnection.

In this sense, I am an artist who is trying to strip the imagination out of AI, rather than expand our imagination of what it is. We can and should imagine AI differently, but we need to identify the ideology within that imagination first. The AI we have emerged within the context of the world we have, and we can't change AI unless we change that world: its structures, incentives, legacies and logics.

That is a bold order for any single artist. So I should be clear: I don't think my art changes the world. But it can do work, as Ippolito suggests, by "peeling off its ideological wrapper."

Algorithmic Resistance Research Group

In 2023 I was invited to attend the largest hacker convention in the world, DEFCON, for its AI Village. That year, the event was sponsored by the White House, which created some leverage for participation from AI companies. The event invited hackers in attendance — 25,000 of them, if you can believe it — to come into the ballroom for set time intervals and see if they could hack a series of Large Language Models into doing things they were not meant to do. The information was gathered up as a "red teaming" exercise, which is, the data was passed on to those companies to analyze and potentially fix.

Even critical AI art could be said to have some complicity with the AI industry.

In that context, even critical AI art could be said to have some complicity with the AI industry: we were their guests, and we were guests at an event creating excitement about AI, with the pretense that the AI industry was working on better goals toward a just society. But fixing models' outputs also created a good face from industry toward the Biden administration, by showing a commitment to "transparency" and community engagement — some of which was true.

At DEFCON, I worked with two other artists — Caroline Sinders and Steph Maj Swanson — to create an ad hoc exhibition of critical AI artworks as the Algorithmic Resistance Research Group, or ARRG! We presented work made with glitches we'd found in these AI systems. They were used as materials to confront the broader social context of AI as an organizing logic – tackling, across the three, concerns about AI that transcend the ethics-washing of inviting a community to solve, unpaid, bias problems in corporate models.

We were invited, before the White House was involved, as a group of outspoken artists, but after the White House came in, it was inferred that we should not be "explicitly political." Steph Maj Swanson was commissioned to make a piece, Suicide III, which was stationed on a screen at the entrance to the hackerspace where volunteers waited before being guided to their seats for the Red Teaming exercise. The screen at first looks like an announcement taking place at the site of the convention, as if Joe Biden is about to address the audience.

So the film presents a deep fake Joe Biden discussing the idea is that there is so much hype on the floor in Las Vegas — hyperstition, specifically, a kind of hype that becomes true through its own assertion — that Biden has to deploy a Department of Counter-Augury to protect the sovereignty of America's future from tech companies building AI.

It was parasitical resistance, not just to platform hospitality, which is how I often approach things, but through parasitical resistance to the hype of the event – itself a platform – that we were participating in. I think we succeeded in testing the limits of an event that had transformed into a kind of spectacle about ethical AI. The organizers were never outright hostile and many of the other volunteers were extremely enthusiastic. But the top organizers of the conference never said a single word to us – and we were not invited back.

AI Beyond Theory

Much of the conversation about AI and art focuses on epistemological aspects of creativity, human thought and expression, or the financial impact on creative industries. I am less interested in these questions because none of that has ever been what my art is meant to do.

Fisher writes of parasites, a movement in which:

"The digital is not necessarily the medium or site of exhibition of these artworks; it is the informing condition of their emergence. The digital constitutes a favorable milieu for the consolidation of power structures that predate it, for technologies, sold as empowering, draw us ever more tightly into their ideological mechanisms through apparatuses of capture and economies of dependency. This study reconceives resistance under what Gilles Deleuze famously termed the regime of control, where power has moved outside disciplinary spaces of enclosure and made openness its constitutive promise."

She goes on to say:

"Parasitical works use art as a means to wedge open—to redirect or subtly re-incline—the mechanisms used to justify and legitimize the privatization of resources and access. Parasitism responds to a contemporary political economy in which less powerful players are increasingly constrained and made dependent by the terms of their relationships to more powerful players."

The terms of this relationship, in the AI industry, is what we could call platform hospitality: a certain understanding of the rules you are meant to play by when you use the system. When I use Midjourney, I am a guest. We have to be careful about triggering platform violations lest we get kicked out. This rigidity of behavior constrains us as artists and researchers, who are increasingly turning to misuse to gather data about these systems.

Platform hospitality: a certain understanding of the rules you are meant to play by when you use the system.

As a critical AI practitioner, my art is a way of raising questions that reframe the user's position to technology. In the net art era, the glitch was specific to the browser. Its interface, what browsers allowed us to do and what behaviors they restrained, were enforced as computer code as well as codes of conduct.

Thinking about the world presented to us by the Web helped us to focus on the politics of mediation that interfaces created. Alex Galloway, one of the founders of the net art community Rhizome, wrote in 2015 that "The world no longer indicates to us what it is. We indicate ourselves to it, and in so doing the world materializes in our image." He's writing about the world of the screen, the world presented through our browser windows and media. It is difficult not to look at that passage and immediately think of the manifestation of AI-generated text and images: "Today all media are a question of synecdoche (scaling a part for the whole), not indexicality (pointing from here to there)."

In other words, there are properties of AI generated media that are simply an acceleration of what we artists and theorists had seen before on the Web, rather than a novel phenomenon. As Mackenzie Wark explains, what Galloway was presenting "is a theory not of media but of mediation, which is to say not a theory of a new class of objects but of a new class of relations: mediation, allegory, interface. Instead of beginning and ending from technical media, we are dealing instead with their actions: storing, transmitting, processing. ... [Galloway] is careful not to seek essences for either objects or subjects."

AI art, in the critical strand, understands the relationship here, too, wherein what we see from machines is all simulation and plausibility. Perhaps all of this AI revolution is just an extension of the past 30 years of category mistakes around technology, distinction in name only, the innovation limited to shifts in power and user behavior.

Interfaces, hardware, and content are things, but they are combined through ideologies that structure the relationship between them.

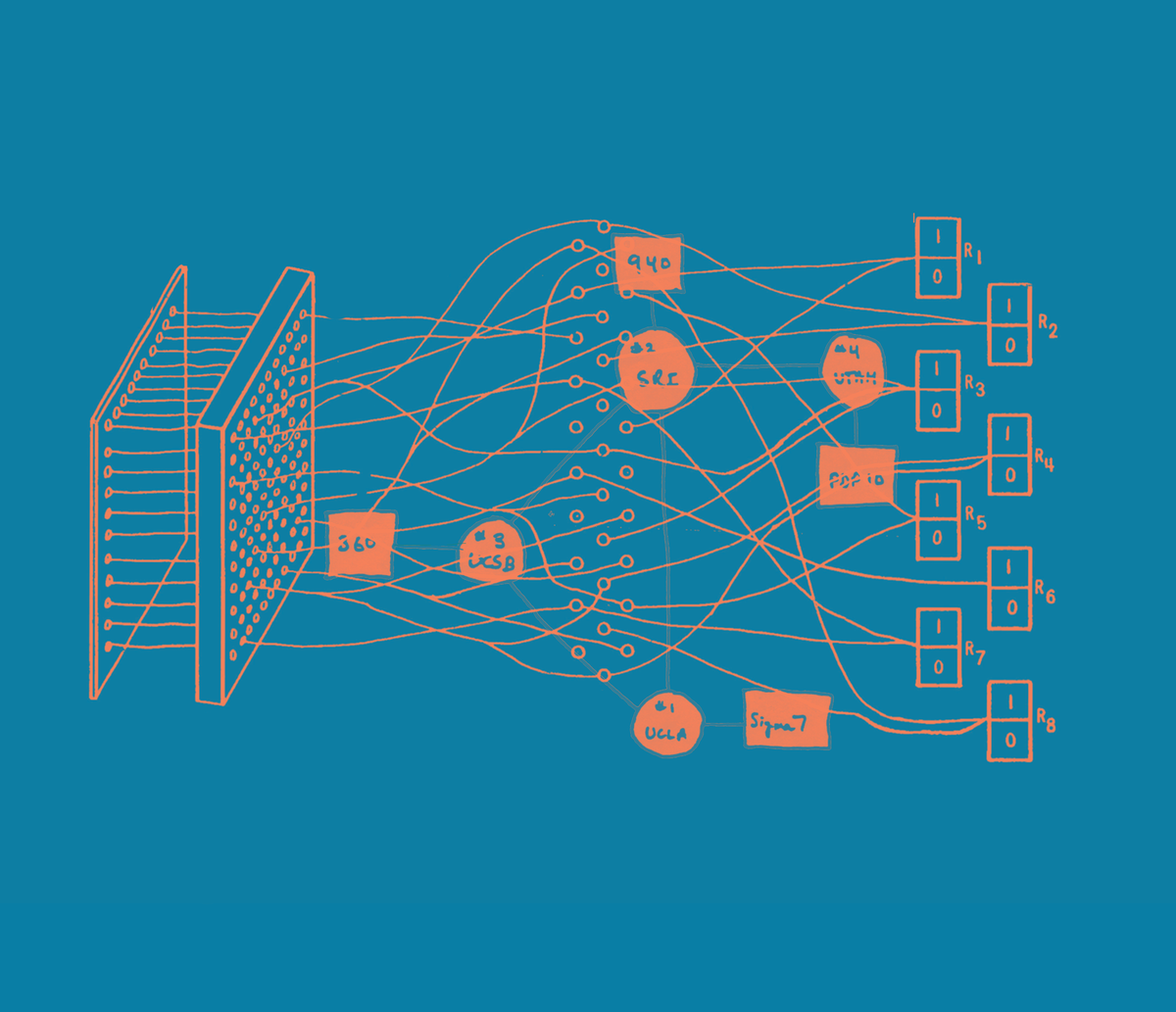

Interfaces, hardware, and content are things, but they are combined through ideologies that structure the relationship between them. Net artists worked within these systems, always conscious that the work existed not merely on a machine or in the server room but in the linking of one computer user to the other through the network: after all, net art was networked art.

Artists get to turn theory into practice, creating ways of living-with or against the technical imposition of political theory. The abstract question that isolates infrastructure from its politics collapses. We get into the technical to challenge the influence the theory has upon it, because that is how we make work.

Being an artist creates a sense of perspective in which no technology is ever taken at face value, that all technology is a surface waiting to be scratched. The honey is inside it, and the trick is trying to get inside the hive without getting stung.

Upcoming Events

Melbourne, July 3: Human Movie (Performance!)

w/ JODI (NL, BE) & Debris Facility Pty Ltd (AUS)

@ Club Miscellania, Melbourne

I'll perform Human Movie as part of a series of performances including the net.art legends JODI and the Australian "para-corporate and parasitic entity," Debris Facility Pty Ltd. Open to the public, details below!

Melbourne, 7-8 July: Noisy Joints: Embodying the AI Glitch

w/ Camila Galaz

@ RMIT Media Portal, Deakin Downtown, Melbourne

The entire conference is going to be great. Here's our part:

Artists and researchers Eryk Salvaggio and Camila Galaz present a participatory workshop on interrupting and reframing the outputs of generative AI systems. Drawing from a critical AI puppetry workshop originally developed at the Mercury Store in Brooklyn, New York, Noisy Joints invites participants to think through the body—its categorisation, misrecognition, and noise—within AI image-generation systems. How do our physical movements interact with machine perception? How can choreographies of shadow, gesture, and failure unsettle the logic of automated categorisation?

Across the session, participants will explore these questions through short talks, collaborative video-making, glitch-puppetry exercises, and experimental use of tools like Runway’s GEN3 model. Using shadows, projections, and improvised movement, the workshop will trace a playful and critical path through the interfaces and assumptions that shape AI perception. No technical experience is required.

Convened by Joel Stern (RMIT), Thao Phan (ANU), and Christopher O’Neill (Deakin).