A Total Portrait With No Omissions

A Short History of Piecing the World Together by its Edges

This week I’m sharing a pre-history of digital scanning, written for artist Ren Gregorcic’s “at the point of a singular horizon,” a series of videos and photogrammetry works opening this month at the M16 Artspace in Canberra.

“Photogrammetry is the science of obtaining reliable information about the properties of surfaces and objects without physical contact with the objects.” — T. SCHENK, INTRODUCTION TO PHOTOGRAMMETRY

“All I want is 20-20 vision: a total portrait with no omissions. All I want is a vision of you, oh-oh.” — BLONDIE, PICTURE THIS

Consider the garden box. It’s a small hole in the concrete, filled with dirt, shaped and positioned by architects in the design of a plaza or parking lot. They’re concrete frames where plants, soils, insects and microbes converge into tiny, isolated worlds. We’re meant to look inside the frames, rather than at the frames themselves.

There, at the borders between natural, built, and virtual worlds, is where artist Ren Gregorčič’s at the point of a singular horizon charts its strange terrain. In immersive images and video, slabs of concrete fuse with leafy greens. Shadows move across trembling weeds, competing with computational sunsets. At first the scenes seem natural, even calming. But a close examination reveals that they are, in a strange way, incomprehensible. These aren't bucolic woodland scenes. They are collages, assembled through a process of automated digital pastiche, reassembling and predicting the behavior of their sources: a garden, in a box, photographed into a virtual box, creating another, digital kind of garden. And along the way, borders between concrete, digital and rendered realities collide and confuse themselves.

Gregorčič’s work is the product of Photogrammetry, or what we might typically call “3D scanning.” Take a bunch of photographs while walking in a circle around an object. Then a computer program automatically connects the edges of those photographs until you — or a computer program — can create a three dimensional model.

While photogrammetry emerged from a desire to document historical objects and structures before they disappeared, the method evolved, literally, from a collapse.

In 1858, Albrecht Meydenbauer, a young Prussian architect, was documenting a cathedral. At the time, this method involved climbing the building with measuring tapes and a compass, like a vertical explorer. When Meydenbauer nearly fell off the side of a spire, he wondered if there might be an easier way. He turned to an upstart technology: the film camera.

The idea was simple. What if he could measure the height of the building in pictures, and keep the climbing gear at home? Meydenbauer modified his cameras into technical instruments, relying on the concept of the vanishing plane.

To understand the vanishing plane, imagine a road stretching away from you in a desert landscape. The lanes of the road never touch, but as it moves away from you toward the horizon, it seems to shrink into nothing. Apply this principle to the lines of buildings in photos, add a bit of math, and you can calculate the edges of a building’s borders, and thus, their size.

Meydenbauer took countless photographs of buildings: same distance, different angles, piecing them together into two dimensional maps of three dimensional territories. One object was always kept in frame to provide a common reference point.

Along the way, he was creating an archive of the world that would endure beyond the loss of buildings and artifacts. He was providing a way to return to them, virtually, once they were gone — for example, Meydenbauer was able to “preserve” the ruins of Persepolis in his images. Today, we use the same process, though digitized, to step into virtual tours of lost World Heritage Sites in Syria: the borders of thousands of images stitched together to create a seamless, immersive recreation of lost places.

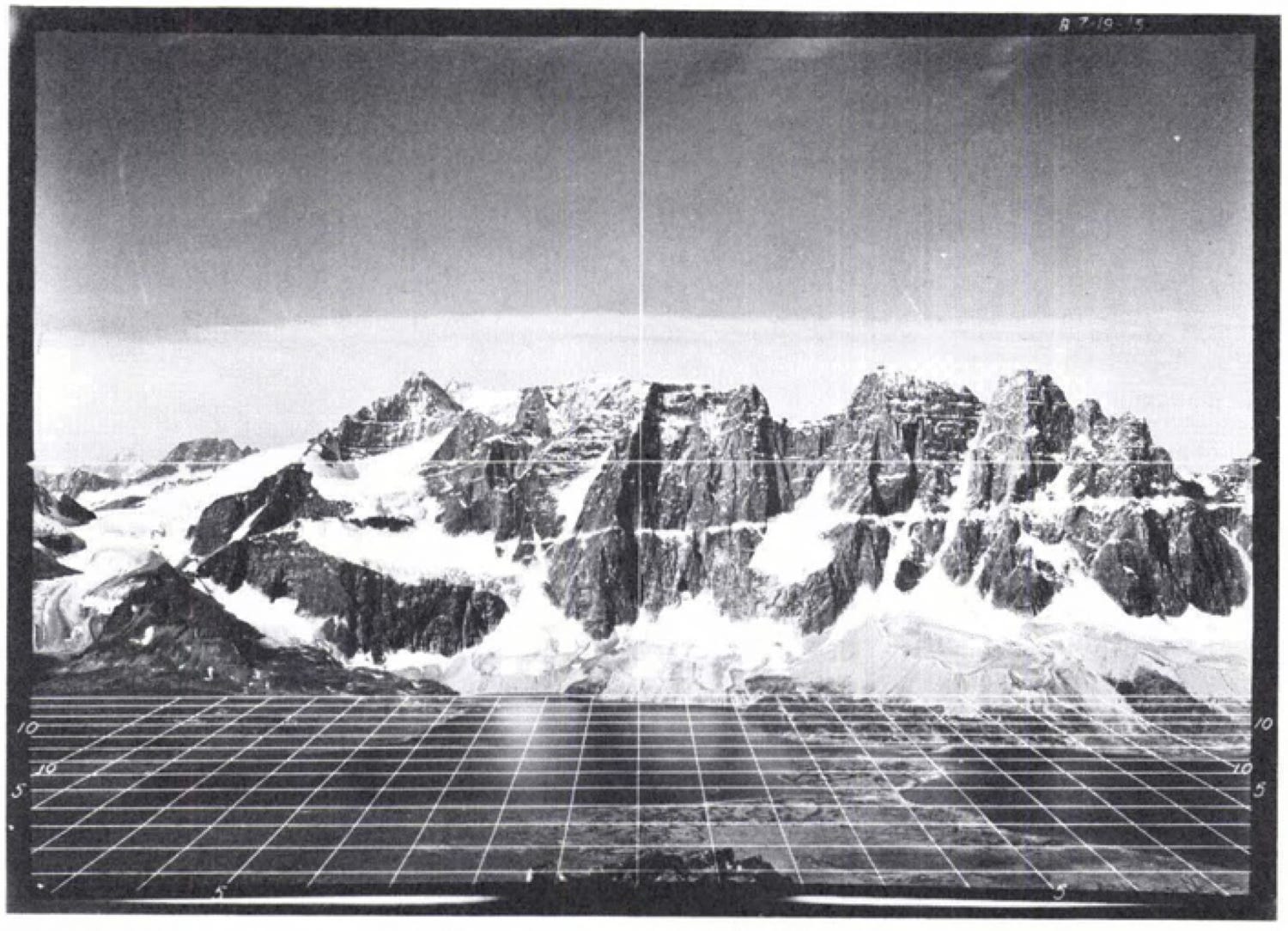

The field has dissolved into the everyday: you can do this to get candy for your Pikachu in Pokemon Go, walking around objects in the world to “scan” them into your phone. The history of film-based photogrammetry is still evident in strange places: the digital grid that we see in 3D image editing software, for example, can be seen in this anachronistic Vaporwave-esque image from 1924.

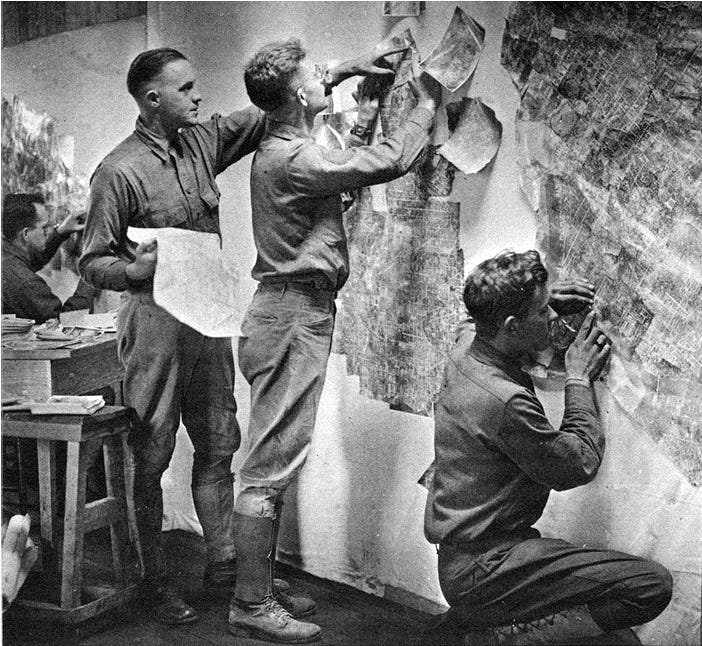

Photogrammetry was also a means of finding the borders of photographs, which became a key element of aerial photography. Air Force intelligence used to piece together overhead film photographs to create a “live” map of enemy territory. Combined with digitals tools today, we’re able to automate this work into massive online maps, through the stitching lines of satellite photos.

Today we can take more images at faster speeds, creating digital models of the entire globe from orbiting spacecraft. Photogrammetry has moved from a box camera outside of a German cathedral to an autonomous vehicle wandering alone on the surface of Mars. It is a boon for the archive and preservation of architecture, of bringing something lost to time or distance closer to us.

All of which brings us back to the garden plot, and rethinking our scale — moving away from distant observers of vast landscapes into intimate observers of small ones. How might it change what we see and how we see it? And what do we make of those borders then — those stitch marks between worlds of the camera frame?

Photogrammetry as a digital process moves from the simple film photograph we might associate with the small intimacies of a snapshot. It is about extrapolation of data from a photographic image, and then reassembling that data into a new, three-dimensional image; a process that is unnecessary for projects of intimate spaces. But this is what Gregorčič’s work does. It shows us the negotiations between different kinds of borders and frames — the physical, the natural, the data-driven — and compresses them into new ways of seeing.

It involves thousands of digital photographs wrapped around predictions of the landscape. The software looks at the images and models the terrain based on what it sees. Then it lays those actual images over the shapes of that imagined terrain. This produces images like those above, which are a collage, a sculptural form in digital space that emerges from the pastiche of bits and pieces of the original “thing” being photographed. The more data, the more precise the model gets put back together. Without a standard reference point — the grid of perspective in that mountain range from 1924 — the prediction slips. The ground falls out beneath our feet. When those assumptions and photographs do not connect, images are stretched and pulled into strange distortions.

When data is missing from one photograph, the system fills those gaps with informed assumptions from other photographs. That's why at the point of a singular horizon isn't glitch art: technically, there are no “errors” in these images. They are the system's best attempt to reconcile information competing at the boundary of the digital and observed worlds. In the garden plot, the concrete mediates the natural space. In rendering this as a 3D object, the observed and digital begin to seep. Renderings of the relationships between these boundaries is at once familiar and disorienting. There is a fuzziness in the process that you can see in these results, which feel like a computer dreaming of gardens.

I’m reminded of the nursery rhyme about Humpty Dumpty: the egg shells shatter, and all the King’s horses and men can’t put the egg-man together again. Photogrammetry does what knights and horses can’t: it can reassemble buildings from an archive of shattered pieces, thousands of photographs split apart and reassembled into a virtual Humpty Dumpty. The cracks still show in the seams, and Alice couldn’t have a chat with him: the original is broken. You can only remember the egg you have lost.

After a global pandemic and environmental catastrophes such as 2020's bushfires, a digital archive of garden plots — natural spaces already shaped and defined by concrete — evokes something irretrievable. It feels to me like a science fiction archive of vestigial green spaces surrounded by concrete, as if it was all we had left of nature: digital time capsules for when even a garden plot is as far away as the architecture of Persepolis, an archive of a physical world teetering on collapse.

I come back to that core definition of photogrammetry and it’s lack of physical contact with the world we want to understand. These images are seductive, but distant: calming, meditative, but nonetheless, approximations of nature by a machine that cannot touch the world. If there was something whimsical and naïve about preserving life through measuring sticks, compasses, and a roll of film, at least the physical contact made it seem real, verifiable. Concrete touches the garden's edge, but the digital model watches from afar, telling what it sees from the logic of detached surveillance. at the point of a singular horizon reveals the unevenness of interaction at a distance. These works live between things, emerging from the edges of a physical world and the collection of its measurements.

Things I’m Watching This Week

- Can’t Get You Out of My Head

Adam Curtis, BBC

Adam Curtis’ All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace was one of the most influential documentaries I’ve seen in my lifetime, looking at the roots of cybernetic thinking and the ideology that it produced. If you don’t know Curtis’ work, start there. Though Curtis misses the mark at times, he always raises fruitful, counterintuitive questions. The new doco is six parts and makes for bleak breakfast viewing, but was well worth it.

We may be stronger than we think. Social media can put us into a state of hysteria, but it can’t fundamentally change the way we feel. Our real problem is that we don’t actually have any kind of alternative idea for a society. So what we do is embrace a dark pessimism that says, “Oh, we’re being manipulated.” It’s a way of avoiding facing those difficult questions the Left has retreated from over the last 10 or 15 years.

- Future Continuous : Present Stream

A documentary Web series exploring visions of the future through art, cultural theory, architecture in Los Angeles. The first section looks at the history the iconic Bradbury Building in LA, one of the first in the city. It’s architecture looks simultaneously like a shopping center, a train station and a spaceship, and it features prominently in sci-fi like Blade Runner. It’s a great start to an exciting series.

What I’m Reading This Week

The most common misconception that scientists have about artists is that they are chaotic, or are simply illustrators helping to educate the public about science. What gets lost is the deeper meaning that the artists could give to scientists. Artists are trained to educate themselves on a variety of topics so that they can offer critiques on life, society and politics, and those skills are transferable to science. —

The Kicker

The filmmaker Stan VanDerBeek made a series of computer-based, animated poetry in the late 1960s. The works superimpose early computer graphics over 16mm film footage. A few of them are available on UbuWeb: Poemfield No. 1 and No. 7 are nice. It reminds me that the limits of what our machines can do are just as big a part of their aesthetic as the things machines suddenly make possible.