A Tourist's Guide to Datasets

Metadata as Memoir

When engineers want to teach a machine how to see objects in the road, one way to do it is to look at the ground. When objects on the ground interrupt that line of sight, a camera can, in theory, send a response to the brakes of an autonomous vehicle (AUVs).

In 2017 Volvo had trained its AUVs to look for objects on the ground to avoid collisions. But it couldn't account for kangaroos. When a kangaroo jumped, the system read it as moving further away, to the horizon. The system recognized Swedish land mammals, things like elk and caribou. Kangaroos, though? That was wizardry.

Machines don't understand reality, they understand models of reality. Those models are described to it. The way we describe the world to create those models is through data. To get a system working, you have to translate observations into data, limited by the constraints of your system. Someone decides what matters most to get that system working. The most salient observations turn into data, the least important get discarded. That relies on subjective judgments and frames of reference. For example, there is no need to warn a system about Swedish kangaroos.

Lots of problems can worm their way in through gaps left by what gets discarded in a dataset. Even more come through when that dataset gets adapted to other purposes that they weren’t intended for. If you collect data on one population, or one place, it's very unlikely to be usable in others.

“Most data arrives on our computational doorstep context-free and ripe for misinterpretation. And context becomes extra-complicated [with] poor data documentation.” — Catherine D’Ignazio & Lauren Klein, Data Feminism (2018)

Through my coursework at the School of Cybernetics at ANU and now with the Civic Software Foundation's Emergent Lab for Context-Aware Systems, I've been thinking about data collection practices and how they might be improved. Or at least, designed to make clear the risks of taking them out of context.

Data gets recycled by people who don't know where the data comes from. They don't know what decisions informed it, or what the limits of the data were. But making data available for others to use is a nice gesture, too. It helps people create meaningful work, or projects, without starting from scratch.

How could we guide tourists through our datasets? How could we set appropriate boundaries for their use and prevent abuse of the data as it moves from one purpose to another?

One idea I come back to is the Tourist's Guide to Datasets. It was something I came up with while I was collecting air quality (AQ) data in Australia shortly after the 2020 wildfires. I was gathering AQ readings at various points around campus. Rather than relying on the sensor's output alone, I stopped to take notes at each stop:

- I took photographs of the location.

- I wrote down what it smelled like.

That’s useful for tourists to my data. It was the difference between thinking a piece of campus has noxious air quality vs knowing it was a passing lawnmower. But I also wanted to use the dataset to convey what I had assumed about the data. That way, if it found its way to a web site where random people might try to use it, they can build off of my knowledge. So, the dataset has annotations:

- I marked concerns about the data we collected. The goal is to produce useful data. It wasn't to position myself as an immaculate researcher. It was important to clarify whatever seemed anomalous or beyond my expertise. (I define that as the mark of an excellent researcher).

- I offered a description of what each Air Quality metric meant in layman’s English. I had no idea what my data might be used for later. So it was important to define terms precisely. That helps avoid misunderstandings or international/interdisciplinary losses of meaning.

Since then, I've been thinking about creating "A Tourist's Guide to Datasets," a kind of journaling tool that could be used when collecting data. Almost like a memoir, or a tourist's book for visiting a new city. It centers the reality that the data point is one fleeting moment captured by one person, who interprets it according to a variety of personal factors and references. It’s something like a digital map, which allows you to click on a single location and access more information about it, but for data points.

Sure, you could create extra fields in a dataset to save information, but that restricts you to the information you can consistently record, creating an unmanageable and time-consuming series of additional rows or columns in your spreadsheet. Bringing it in as metadata on individual points creates greater flexibility, allows for better communication and translation, and pierces through the illusion that the data we gather can be trusted as “objective” or “neutral.”

Xavier de Maistre wrote a kind of adventure log exploring the confines of his home, where he was imprisoned in 1790. He wrote about it in the way that an explorer might chart the climbing of an uncharted mountain, or a sailor might chart some newfound seashore. It is a loose assemblage of observations, reminiscences, and stray thoughts about the space where he lives.

“There’s no more attractive pleasure than following one’s ideas wherever they lead, as the hunter pursues his game, without even trying to keep to any set route. And so, when I travel through my room, I rarely follow a straight line: I go from my table to a picture hanging in a corner, from there I set out obliquely toward the door.” — Xavier de Maistre, “A Journey Around My Room.”

Datasets are models of the world, slices - rooms - where a machine imagines the world, tracing lines between the information points. But there isn’t a lot of richness between those points, not a lot of information to contextualize them outside of what is needed for the machine to “keep a set route.” It might help to reimagine “big data” for what it really always has been: an assemblage of small datasets, a series of “rooms” that make up the interior of the “house” we want to model.

It is altogether messier — and a crucial reminder of human messiness — to include the stray thoughts around a single data point. I can envision an entire literary movement around collecting datasets from our physical world, describing them in the human-legible details that make things make sense to what’s in our skulls rather than what’s in our phones.

Things I’m Reading This Week

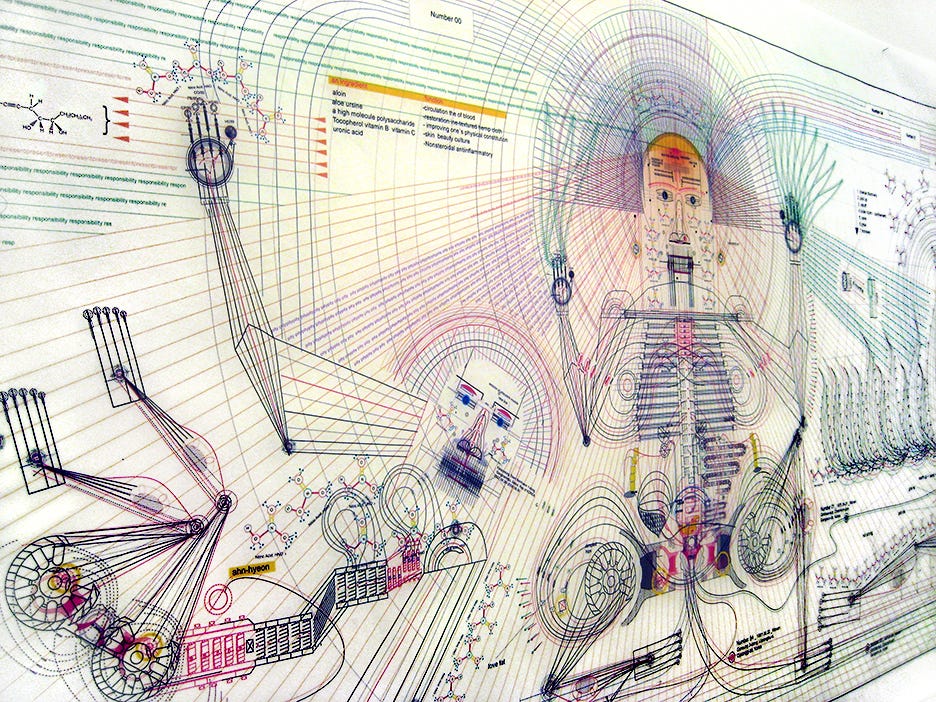

Minjeong An

Minjeong An

Minjeong An is a South Korean artist who uses systems diagrams and mathematical, scientific languages to express small moments and domestic personal relationships. The extract above is from “Mother Distributed Aloes of Her Own Cultivation among Her Family” (2007), and it portrays “six members of my family gathered together massaging with aloes that my mother had grown herself” while charting the complexity of that family through lines — reflecting relationships, histories, and connections. She has also illustrated a “Mother’s Hand User’s Manual” (2013) reflecting on a single interaction to track an entire history and context of her family story.

###

Mobilizing the intellectual resources of the arts and humanities

Shannon Vallor

A well-written and persuasive piece about the drift away from ethics in envisioning AI futures, and the role of arts and humanities to get it back. My one complaint, though, it seems to continue the trend of “arts and humanities” defined by things such as literature and philosophy, leaving out a rich tradition of digital and media art that poses these questions and aims to do this exact work.

Technologies are ways of building human values into the world. There is an implicit ethics in technology, always. And what we need to do is to be able to make that implicit ethics explicit, so that we can collectively examine and question it, so that we can determine where it is justified, where it actually serves the ends of human flourishing and justice and where it does not. But as long as the implicit ethics of technology is allowed to remain hidden, we will be powerless to change it and embed a more sustainable and equitable ethic into the way the built world is conceived. The arts and humanities are vital to recovering that possibility, and ethics is a part of that.

###

Gaslighting Your Boss: Creative Experiments in Digital Sabotauge

Sam Levigne

A whistle stop tour of the artist’s digital artworks:

For the past few years, one area of my artistic research has been centered on the concept of sabotage within the emotionally and materially blurry context of digital technology. As an artist, I examine how data-driven systems are transforming practices like labor, policing, shopping, or even dating. My work often takes the form of software experiments that hijack technologies or methods from industry, re-deploying them for ends that were never intended by their creators. In doing so, I attempt to reveal the politics and power structures inherent in the systems that mediate our lives.

Thanks for reading!