Artificial Intelligence is a Compost Heap (Ideally)

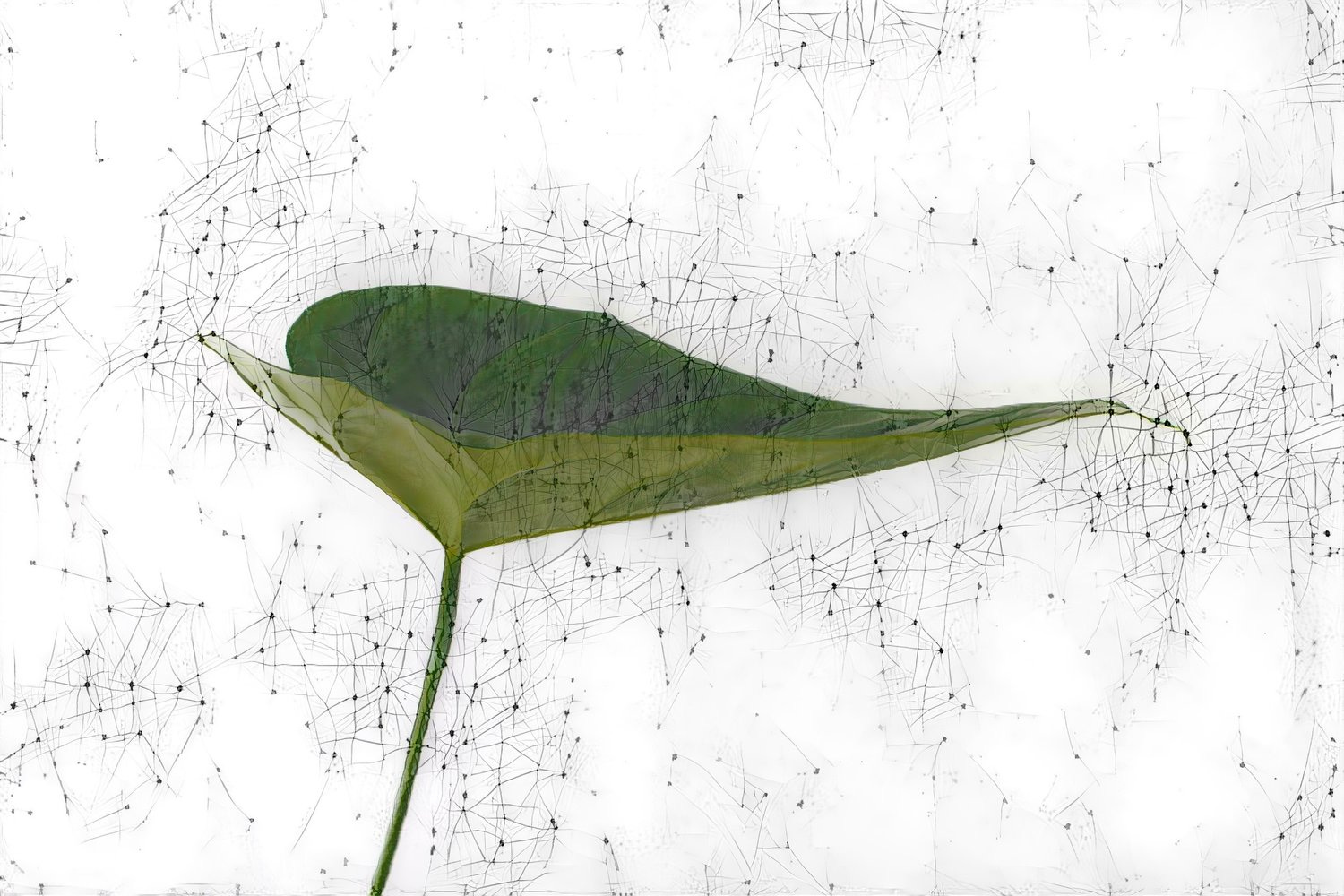

Looking beyond the human mind for new metaphors of intelligence

Our new yard has trees, so our new yard has leaves. We raked up enough to fill seven paper bags which we stored in a small shed out back.

We asked around, and the options were to burn them, or wrap paper bags in plastic bags to take to the landfill. Both options violated our sensibilities, so we built a compost cage.

It's a pile of leaves, and we add food waste roughly every three days. So it's a pile of leaves, coffee grounds, egg shells, leeks and garlic skins, and grass from lawn mowing. When the snow lands on the compost, it has a weird bubbly texture, so we assume it's working.

I spend a lot of time thinking about analog and digital metaphors. Much of that time I'm drinking coffee, so these metaphors tend to get stirred into the pile with the grounds. If you're looking for more helpful metaphors for imagining artificial intelligence, follow our dog to the back of the shed. It's a good time for it. Not only is the compost three feet high, but our metaphors for artificial intelligence are facing their limits.

Metaphors are language, and language is social, and so metaphors are ideological. Metaphors put something at the center. For AI, it's right there: "intelligence," built on models of the brain. Computers have "memory," but their memory has nothing to do with ours.

AI doesn’t work the way a brain works, AI works the way models of the brain work. Technicians designed those models to work on computers from the outset. In a few decades, we've become good at those models, and the human brain has nothing much to do with it.

What if "AI" was a compost pile?

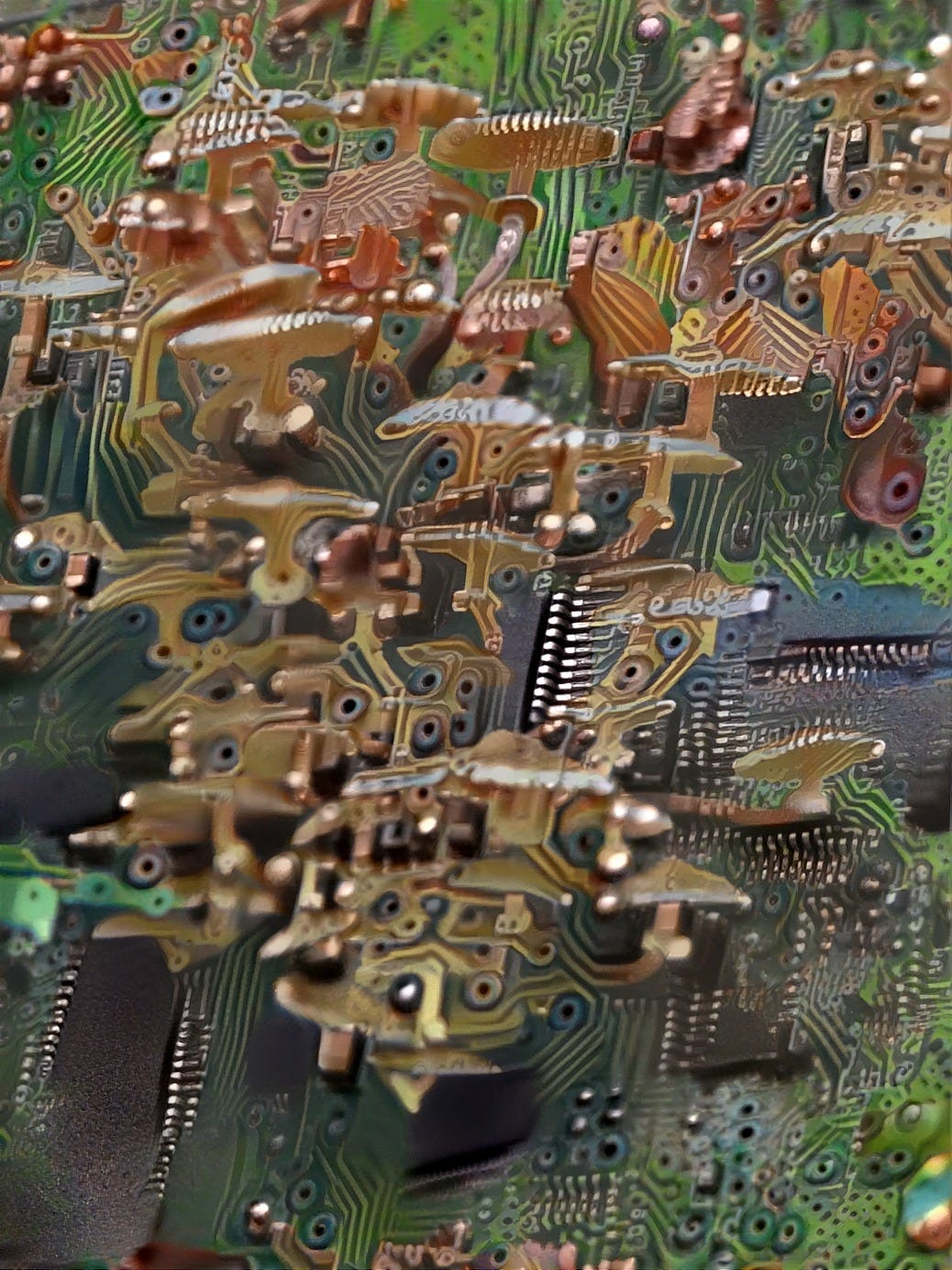

A compost pile is a living system. It breaks something down and reorganizes that material to produce something new.

There are different ways to compost things, but I only know what’s out back. That system started with leaves. Bacteria and fungi are eating the leaves, breaking them down into smaller parts. Along they way, they’re releasing nitrogen and potassium. Protozoa and worms will come along to eat those bacteria and fungi. Bigger worms — along with beetles and millipedes — will come along too, and eat the smaller protozoa and worms. I stir the leaves every so often and add fresh leaves as I get them, along with used tea or browning spinach.

So I have a pile of “data” sitting in my yard that needs to break down: leaves. To get the task done, the pile needs to break that information apart into its smallest elements.

Take object recognition, an automated task where we have modeled the human brain to some degree of success using today’s brain-centric metaphors of neural networks. It’s built on the idea of how human brains learn and acquire new information: by seeing a tree a hundred times, figuring out common properties between all 100, and then guessing whether the next thing you see is a tree or a houseplant. As you get more information you can refine this into narrower categories, distinguishing elm and birch and oak (or a very tall deer, or a telephone pole).

There is nothing wrong with that learning metaphor, aside from confusing AI models built on those metaphors for how actual biological brains work (which happens all the time). But there is no reason it needs to have a monopoly on definitions of intelligence. It is evaluative, comparative: quantitative, and quite bad, at the moment, at capturing dynamic information. You can’t really treat social behavior the way you treat 1000 pictures of a tree, but we try anyway.

The human brain is just one of many walnut-shaped things that solve problems. My dog navigates the world in ways I don't. I am visual, I see and describe, through language, the world around me. For her, scent dominates her memory and comprehension. A compost pile "senses" things too, distributed between organisms worming around in mulch. It's a systems intelligence, at odds with the solitary brain-model of AI's digital brain.

The digital brain metaphor works pretty well for computers chugging away at pattern recognition tasks using inanimate objects. It's a solitary, individual model, processing a limited world of static information, making predictions, and acting on those predictions based on limited information — a solipsistic machine.

Challenges emerge when we apply that logic to dynamic social interactions. For that, a metaphor of compost intelligence might be more helpful.

There’s a lovely paper on memory metaphors by William Randall published in Theory & Psychology. Randall contrasts the logic of a compost pile with that of a computer. Randall is, in essence, marking some distinctions between analog and digital ways of imagining and relating to the world:

“Where computers are mechanical-electrical in nature, compost heaps are as natural as can be. Where computers are about the processing of information, compost heaps are about the producing of ... compost. Where the former are fundamentally sterile, the latter are fertile, by definition. Computers do what we instruct them to do, passively, as it were, whereas compost heaps do what they do primarily on their own, with very much a life of their own. Computers are about ordered activities whereas compost heaps are about what, in contrast, seems far more chaotic. Indeed, they are not ‘organized’ so much as ‘organic,’ in large part because their hardware and software are effectively one. To continue, all of the files stored in the memory of a computer are, in principle, equally retrievable, no matter when they were composed. Moreover, the information contained in them is preserved precisely as it was when the file was last edited and saved. With a compost model of memory, however, recollections of more recent events—or what remains of those recollections—are generally more retrievable, since they are, after all, nearer to the top. Meanwhile, events which happened further back are buried deeper down. And the deeper they lie, the less retrievable they are likely to be.”

Metaphors matter because they shape the way we build but also what we build toward. They steer us toward consistency of the model, reward clever connections, encourage neat analogy over recognizing unique properties of a system. Along the way, we build a Tower of Babel, a central spire around which we understand a thing. Metaphors falsely transform into references. Then, inevitably, the tower collapses as we hang too much imagination on those metaphors, straying from the thing that is. We lose the thing to the thing we imagine it to be like.

So what happens if we flip some metaphors around, embrace the metaphor of compost to imagine and design AI? In a playful way, just for funsies, not for reification. Just to see what happens.

A few thoughts rise up as I walk toward the heap with a glass jar full of edamame shells. Here are six of them.

1. Decomposition

First, data begins to decompose. Right now data centers warm the Earth storing data that has lost relevance. The decomposition of data frees up a lot of energy. It creates systems biased toward recency, introducing greater dynamism to automated decision making. How long does your Amazon purchase history need to exist? Past decisions need not be the sole basis for future predictions. This would return a bit of agency to the user.

I think about what Andrew Pickering said at the recent New Macy meeting:

The phrase that comes to mind is “shallow data.” Rather than extrapolating for all time, you could just ask, “what did the last 10 people do?” It would be a great way to create new patterns, as we can’t get big data anyway.

Likewise, what Ellen Broad describes about the decomposition of data centers and temporary webs in her “Redesigning Artificial Intelligence From Australia Out” keynote:

We can reconfigure engineering practices in AI to look outwards, as well as inwards. We can set expectations that building a system means taking into account, and taking steps to address, its unintended effects on the ecosystem within which it will operate. We can cultivate a culture where what distinguishes you is not the simple extravagance of the web you create, but how you care for it, and how you take it apart.

2. Homeostasis

Second, it would be designed for self-regulation rather than self-sufficiency: homeostasis, in the cybernetic parlance. Homeostasis is the ability of a system to control itself within a wide variety of contexts, avoiding snowballing toward the extremes. You need to design structures within the system that "control" the system. You need mites to eat microbes. Stafford Beer shows how speed regulation works on a governor: through feedback and interactions, understanding information as a state of position (literally, a bar is up or not) and reaction:

Crucially, a homeostatic system operates within an environment, and must maintain that environment. At odds with Beer — “control cannot be imposed on the system from outside” — it’s worth asking where the boundary of a system truly rests. The boundary of compost might seem to be the chicken wire fence it’s wrapped in. But what enters that system from beyond the chicken fence are still a part of that system.

From the type of leaves to the varieties of food it’s fed, to the quality of the oxygen aerating it, to the worms rising from the soil below, to the rain falling from the skies above it (or the absence of rain), to the dogs pulling at the stray sticks that fall in. A compost heap does best when it does not interfere with these things, but lives within them, and so might our machines, if we imagined them right.

3. Accommodating Variety

Compost is a conversation. There is what’s inside the marked boundaries and what is outside the marked boundaries. They are part of the same system, but all parts of that system need to communicate, rather than follow fixed sequences. Today, we don’t train autonomous vehicles to stop by asking when a human is most likely to stop. But we design plenty of other machine learning systems that way. You aim to design an autonomous vehicle that is in conversation with its environment.

You can't control the vibrant dynamics of human activity, nor should you want to. As an example of what happens when you do, we have Facebook. Facebook should first be understood not as a “social network” but as a conversational mediation system. It is designed not to expand your social interactions, but to limit and mediate them for profit. That’s not even a critique! It’s just exactly what the technology is if you define it by what it does.

In Anarchist Cybernetics, Thomas Swann points out one example among many of the company’s design decisions that make this mediation easier for them: Facebook doesn't let you embed hyperlinks or code into status updates. It obscures external links on your feed, because leaving the site defies the market imperative to keep you logged in and looking at ads. This is control at the expense of variety.

Facebook's mediation machines steer human conversation toward a limited vocabulary of actions, in the name of control. That way, humans fit into the limited intelligence capacity of that conversation mediation system.

That's not compost. Compostable social media might aim for organic control over its look, feel, and design rather than organized control over the user. It would interpret content as a series of signals: a heap that could attract or repel users according to their own, self-created, emergent incentives. Which brings us to point four.

4. Emergence

Within a metaphor of compostable intelligence, things grow: information emerges. Currently, AI rhetoric emphasizes prediction. That's tied to point three: emergence tends to undermine control. Left alone, a compost heap might spawn a watermelon, a tomato, grass, or a pine tree. An autonomous vehicle, ideally, does not become a watermelon at an intersection.

But human interactions cultivate emergence as the goal of productive conversations. Play emerges. Understanding emerges. Ideas emerge. Here, metaphorical watermelons might bloom when a pine tree was expected.

Context is a vital aspect of the compost heap, and emergence is crucial in certain contexts. When mediating social activity, for example, the metaphor of compostable AI emphasizes emergence as a goal rather than a distraction to be tamed.

5. Intent

Compostable AI would view data like fallen leaves. We do not create compost piles with the intent of creating more leaves, nor do trees bloom with the intent of creating compost piles. There’s nothing wrong with leaves. But it is part of the system rather than a goal of the system.

Imagine designing a compost pile that only grew rotten food, so we can endlessly expand the pile and generate even more rotten food. There's probably no better description of social media's data collection system than that.

Data can be valuable. It can also be debris, abundant and unwelcome clutter generated by organic activity. Data is essential for operating a system, but it rarely needs to be the primary focus of the system.

We create compost piles with the intent of transforming leaves and souring chard into something fermentive. We want the data to become something else. Arguably this is the goal of our systems today, but it doesn't seem central to the design logic of many of the things we use.

6. Nurture

Compost fails without attention, effort, and consideration. Last week, my dog got into the compost, pulling out three coffee filters and eating an unknown quantity of coffee, which can be toxic to dogs. She’s fine, but it points to the limits of “self-sufficiency” and “autonomy” as system goals. Even a self-regulating pile of leaves and worms can poison a dog.

Processes can happen on their own, but are tied to agents-in-the-world. The compost requires human care and thoughtfulness. Without it, the system fails.

As Donna Haraway explains it:

Well, you can do compost badly, which I also like. I like that about the term. You can neglect your compost. You can put the wrong things into it, you know, industrial (or, for that matter, organic) meat in it. You can fail to turn it over. You can put it in an inappropriate place so that it draws critters who shouldn’t be drawn to compost, and whose lives then are themselves in danger from people, like raccoons, but who also endanger others. Compost is a place of working, a place of making and unmaking. And it can be a place of failure, including, well, culpable failure. Compost can be a place of doing badly. And I like that aspect of compost, having had some failed compost piles in my life!

Haraway has written about "compost societies," spaces which are co-created by ever-changing arrangements in the social mud. Humans interact and those interactions generate outcomes. There are, nonetheless, boundaries and control within the compost system as a "machine." It is an interactive machine. It's designed and built, rather than spontaneously emerging, even if leaves scattered in the woods have similar behavior. It is not just the gathering of leaves, but the mixture and the nurturing, that create the richness of the outcoming soil.

Conclusion

The human brain, and speculation about how it works, has certainly gotten us somewhere as a species. And while the flaw of that brain is the fact of its solipsism — the world is endlessly assembled and reconstructed within it, based on observation and feedback — the bodies beyond our skulls are the things that take action in the world. We are interacting through a mesh of internal and solitary sense-making, and through communication, a consensus emerges.

But we have to look at this consensus a human one. The world looks the way it does through that brain. Looking beyond our own heads is a greater step toward empathy and kinship with the surrounding world. It is one more place to look for knowledge about how the world operates, communicates, and exchanges. We have already, and will, build machines that operate within that network of relationships. The question is how they might be integrated.

If our metaphors define the spectrum of possibility, then let’s look for some metaphors beyond ourselves, and see what happens then.

Thanks for reading. I’m on Twitter as @e_salvaggio if you want to find me. Feel free to share this post or, if you haven’t, subscribe for future writing, never more than once per week (it’s free, though donations are welcome).