Automating the Delta Blues

The Relationship between AI Music, Black Art, and Black Money.

You don't have to go very far back to find examples of black artists creating work for nothing. The short film Black Art is Black Money documents her story in the context of Picasso, Elvis, and the long history of white profits from black art, creativity, and ideas.

Take a look at Jalaiah Harmon. A 14-year-old in Georgia, Harmon created the Renegade: a dance move that swept TikTok, pep rallies and K-pop in 2020. People picked it up from her Instagram, copied it, passed it on without any credit. This eventually filtered out to another (white) teenager whose online audience has over 9.2 million subscribers — and is now considered the "CEO of the Renegade," while Harmon struggles to get attention, credit, and the lucrative opportunities that come with viral fame in the dance world.

I'm living in Memphis, Tennessee, home to a rich history of black musicians and the artists, like Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins, and others — who steeped themselves in the sound of black music and generated a version of it for themselves.

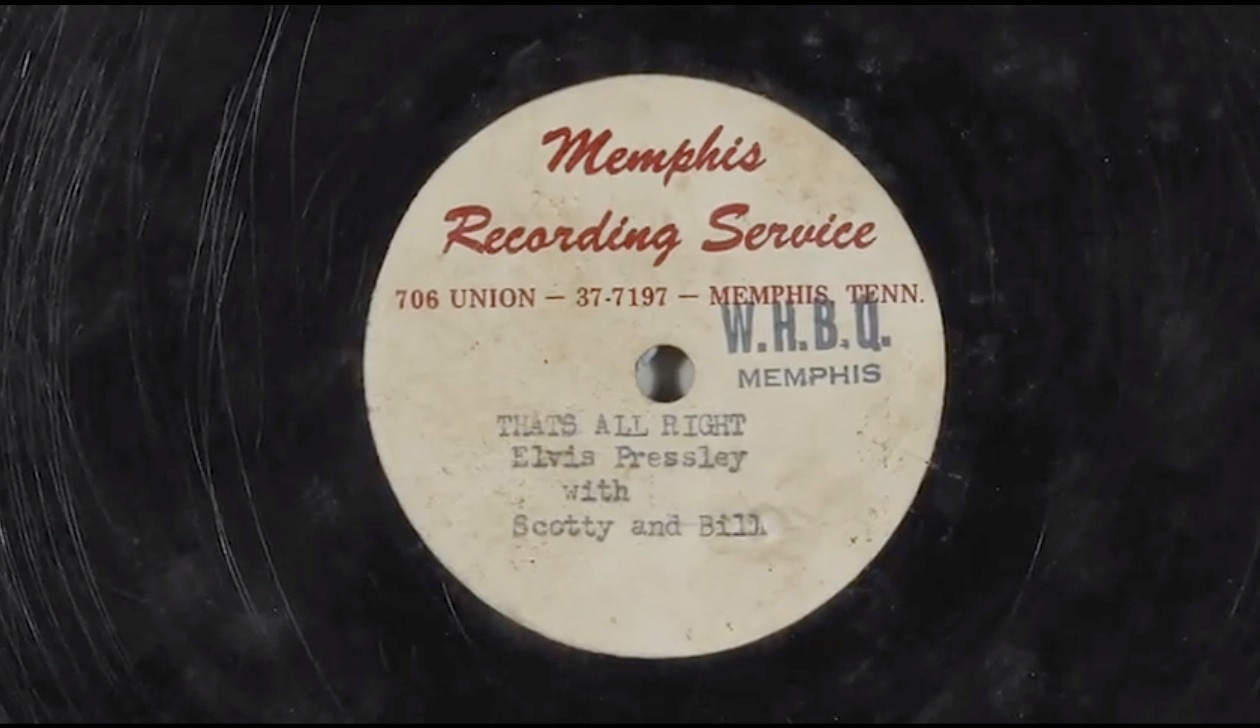

On July 5, 1954, Elvis walked into Sun Studios (then called the “Memphis Recording Service”) and recorded "That's All Right," originally performed by the black artist Arthur Crudup in the mid 1940's. The owner of Sun Studios, Sam Phillips, had written years before that, "if I could find a white man who had the Negro sound and the Negro feel, I could make a billion dollars." He signed Elvis, and the rest is history.

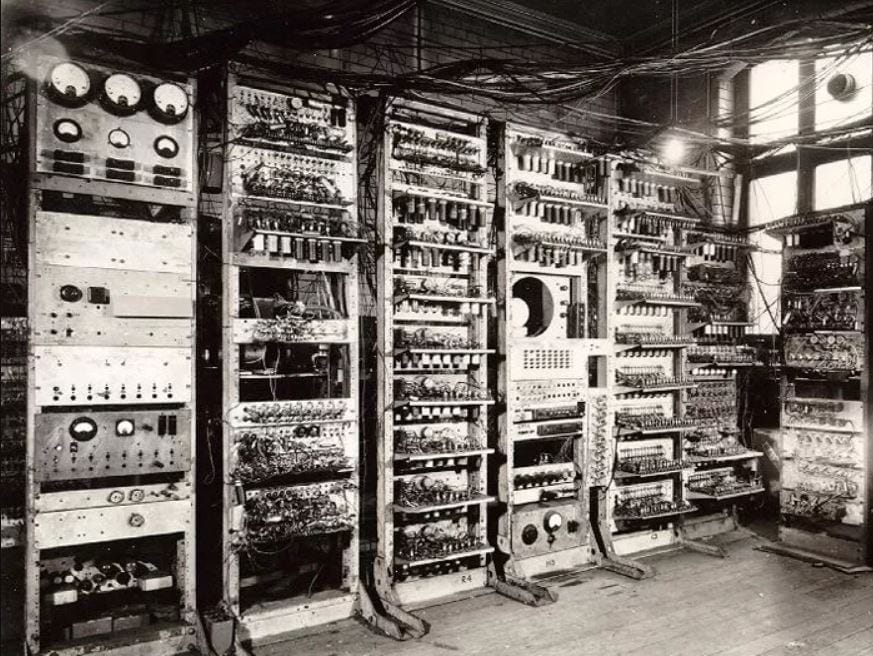

At the same time, in Princeton, New Jersey, another kind of musical emulation was being attempted at the Acoustics and Electromechanical Research Laboratory of RCA. This one didn't look like Elvis. It was "a three-ton mashup of digital data devices, mechanical and electromagnetic transduction circuits, tuning forks and vacuum tubes, punched paper rolls, wire brushes, relays, resonator chains, amplifiers, speakers, and disc recorders” (source). That is, it was the first true synthesizer, RCA's Mark-1.

Martin Brody's deep (and paywalled) research into the history of the Mark-1 suggests that the ideology of the Mark-1, coming from American labs, was aiming for it to be a humanist machine capable of creating new forms of artistic expression. Yet it was trained on master performances of player piano records, designed to emulate Chopin and classical musicians. If it did not replace the composer, it aimed instead to replace the virtuosity of musicians: in every home, a Chopin.

One of the architects of this software, Milton Babbit, had written a graduate thesis inspired by his own musical writers block. It suggested that a simplified model of all music might someday be possible, and from it, universal patterns could be found and predicted. He hedged this bet, though, and argued that there simply wasn't enough music made yet to learn from. He later went on to work at Victor, where he pursued the synthesizer in that direction anyway: as a way of generating new forms of sound, composition, and performance.

Meanwhile, another RCA employee was having his own struggles.

By historic coincidence, Arthur Crudup, whose music had created Elvis Presley’s career, had signed to RCA’s record label in the 1940s. On top of “That’s All Right,” Crudup had also written songs that would be covered by Elvis (multiple times), Creedence Clearwater Revival, and John Lennon. But Crudup retired in 1950, saying, “I realized I was making everybody rich, and here I was poor.” Crudup had never received any royalties beyond a single check for $10,000, which didn’t come to him until 1971. He died in 1974.

In 2020, OpenAI created a machine learning model called Jukebox. Jukebox, emerging from the same course for electronic music set by Babbit and RCA, is closely aligned with Sam Phillips saw in Elvis Presley. It was based on the idea of learning and predicting. Fed thousands of song recordings, Jukebox does precisely what Babbit said could not be done. Whereas previous AI music had been limited to piano rolls or musical notation, Jukebox produces full recorded materials by artists its been exposed to, from The Decembrists to Kanye West.

Suddenly, like Elvis channeling the sound of Arthur Crudup, a machine could write songs and have the same band perform them. You can now make Elvis perform Chuck D's line from Fight the Power: “Elvis was a hero to most, but he don't mean sh-t to me, straight up racist (f-ck him and John Wayne)."

And while it isn't just black artists whose writing and performances could be replicated, it raises an important contextual question for when it does. The system may do the same thing for Wu Tang Clan as it does for U2, but when it begins producing hip-hop, it hits differently. These systems are trained on archives of recorded material, and produce output that anyone can lift and present as one's own. Or perhaps worse, could be presented as the work of the artist it was trained to perform.

At this stage, sound quality and odd choices abound in the production of this music, but technology moves fast. It is only a matter of time before record labels begin producing collections of artist’s works that they never wrote or performed: a musical body double, without the need for artist’s royalties or demands.

There are no clear rules around detecting, acknowledging, or paying artists whose work is used to produce this music. And it speaks to something else, something exploitative and familiar, when it produces tracks by black artists. Studying the body of work, finding the patterns, styles and sound they share, and then producing them as one’s own product. It is a kind of automated cultural commodification of what has driven American culture to appropriate black artists for its entire cultural history.

This week I'm thinking about automation, music, and commodification.

Things I’m Reading This Week

Herndon is a musician who trains her own AI on her own voice and material. She’s also a researcher, having earned her PhD from Stanford in 2009. On AI, she writes that:

“Through research, I learned a lot of people use existing score material as a training set to create works based on that style, which is basically a statistical analysis of a composer or genre that enables you to make those types of sounds forever. This is so problematic in so many ways in my mind; you get yourself into this aesthetic cul-de-sac, where you’re only making decisions based on those that were made before. To me, that’s not what music is. That process doesn’t make it alive, it makes it a historical reenactment.”

Chung is a classically trained violinist who began experimenting with human-machine collaboration for a series of installations and performances:

“It seems like there is a responsive quality to tools of the modern-day, prevalent in commonplace concepts like autosuggest / autocorrect. This feedback loop of the human/tool/system fundamentally changes the process of making; the canvas is no longer blank. It suggests things to you and nudges you along. It complicates authorship, and it extends beyond creative pursuits to our day to day use of technology. Depending on your perspective, that's either exciting or uncomfortable.”

- Digital Crafts-Machine-Ship: Creative Collaborations with Machines

Kristina Andersen, Ron Wakkary, Laura Devendorf, Alex McLean

Part manifesto, part primer, this artist’s statement takes the position that, because contemporary machines in part rose from the logic of looms and weaving, machine-made art can be understood through the lens of looms and weaving:

“The weaver sits at the loom, moving with the rhythm of the shuttle, quietly counting or cursing, as row by row of lines of interconnected fiber is added into a set of raised and lowered threads. The threads are raised and lowered in different configurations for each flight of the shuttle, adding to the material line by line. A screen, a paper, a punch card holds the abstract of the pattern, but this is only a part of it. The emergent pattern is embodied in the weaver, their movements and rhythms entangled with the blue shuttle, gray shuttle, right-hand flight, left-hand reed, weft and warp, threads and yarns, that together form the double weave, the actual pattern—what is made, what is newly materialized from this hybrid arrangement.”

- Refusing Re-Presentation

Tiara Roxanne

Tiara Roxanne (PhD) is an Indigenous cyberfeminist, scholar and artist based in Berlin. In this academic essay, she looks at the possibilities for Indigenous peoples to resist being commodified and classified by AI. In it, she describes how the collection of images of Indigenous people, which are then used to create “re-presentations” of those people against their will, is an extension of colonialist power.

Created in 1969, Cage and Hiller’s experimental, multi-media experimental music piece was Cage’s attempt at “utilizing the computer to execute the chance operations of the I-Ching.” It is one of the earliest forays into electronic, algorithmically produced music. It makes use of found materials, live instruments, and computer-generated imagery. These were performed in a concert hall with hundreds of found film reels and moon landing footage provided by NASA. Hiller, a pioneer of electronic composition, created computer sound loops. The images in this video are, as best I can tell, the computer-generated imagery used in the concert hall. The piece is so dense it has not just blog posts, but an entire blog dedicated to it.

The Kicker

You can listen to 43 “Elvis” songs produced by OpenAI.

Thanks for reading!

If you liked what you’ve read, please do consider sharing it on social media or telling a friend they should sign up. And if you’ve been reading, why not subscribe? It’s free (though you’re welcome to sign up for a paid plan to support my writing, you’ll get the same content either way).

You can find me on Twitter at @e_salvaggio.