Capturing the Moment

A Snapshot of Scattered Thoughts

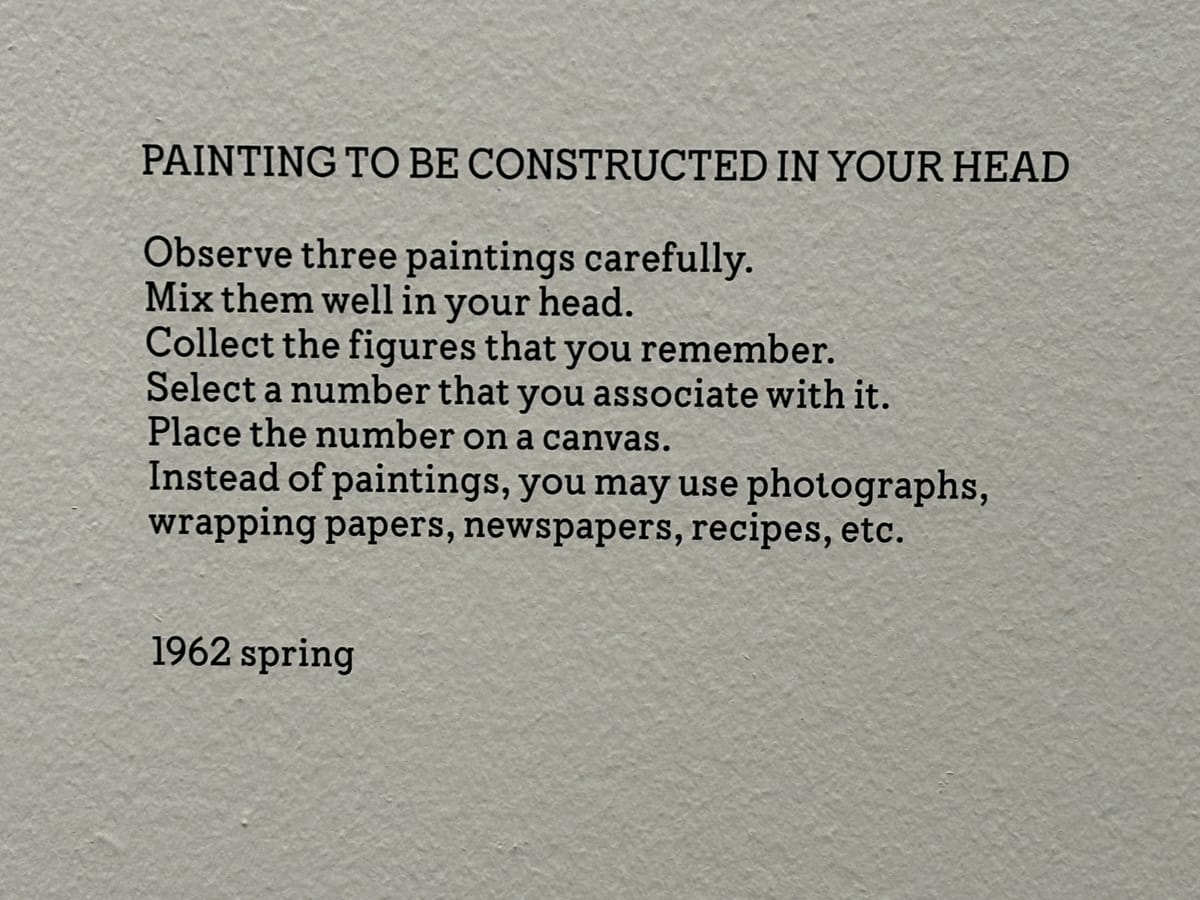

This set of instructions for art is by Yoko Ono. It’s an oddly appropriate description of how diffusion models work. It is also worth noting that this is one artwork, not the history of art itself. So when AI companies tell us that their models create art just like humans have always done, they are in fact referencing a single piece by Yoko Ono from 1962.

I’m starting my residency with the Flickr Foundation here in London this week. Below are some notes from my first two days. They’re scattered, but hopefully interesting, even if they don’t point to any clear conclusions. I hope you’ll consider the posts this month more as dispatches than fully formed texts, and forgive any lapses in delivery, and pardon me if some of these ideas resurface more fully formed sometime later on.

A Generated Family of Man

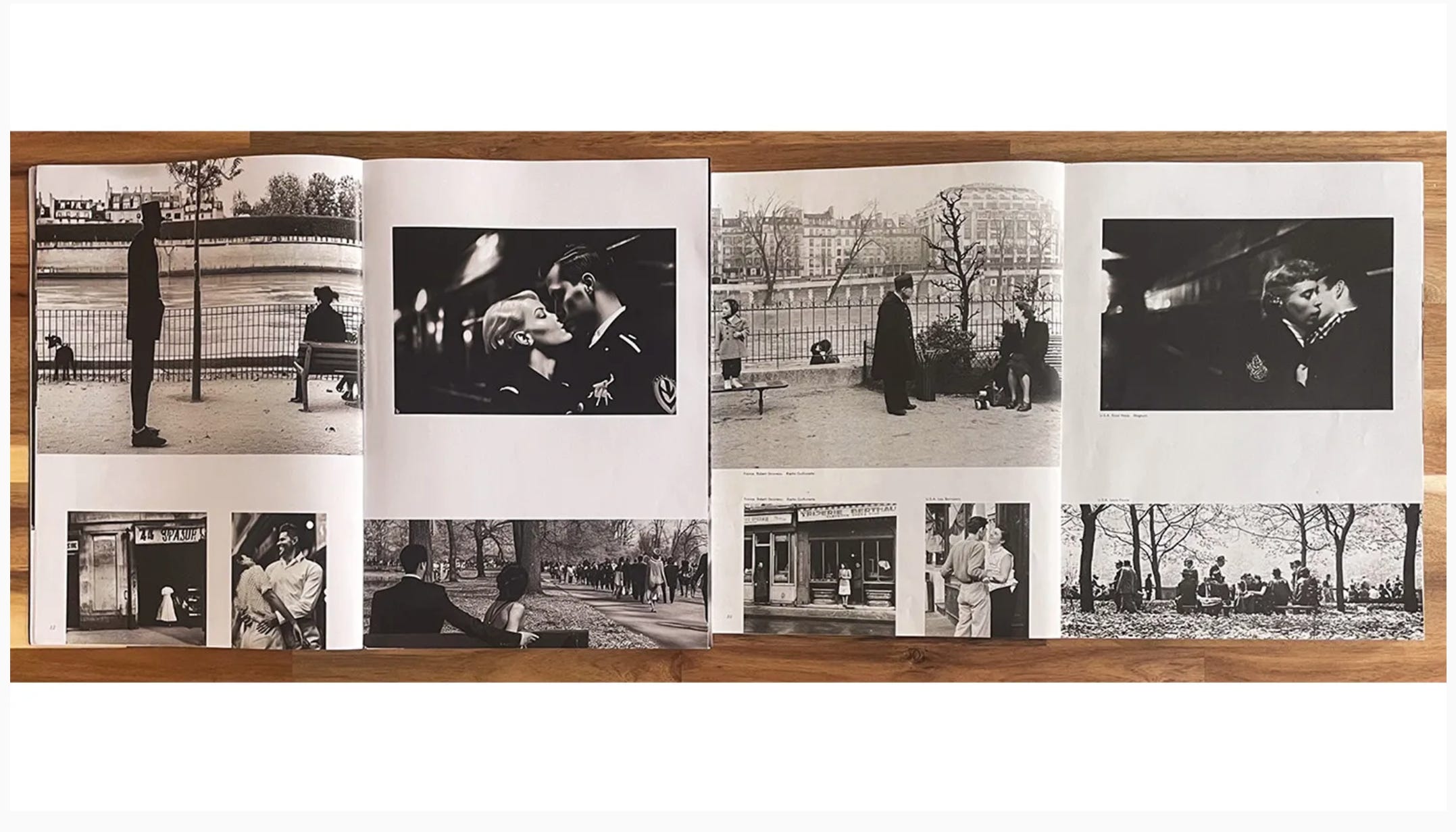

A Generated Family of Man is a project lead by Maya Osaka as part of the Flickr Foundation’s New Curators program in 2023 (more here). The project looked at a 1955 MOMA exhibition of 503 photographs from around the world, A Family of Man, wrote captions for each image and then generated an image using Microsoft Bing. These were then laid out in a nearly identical arrangement as is found in the exhibition catalog for MOMA’s 1955 exhibition, allowing a direct comparison of photographed and synthetic images.

That’s precisely what I did this Friday — my first day in the office of the Flickr Foundation, in the neighborhood I lived in back in 2013, an unstarving distance from the food stalls at Borough Market. Perhaps for this reason, comparisons of uncanny representations were on my mind, as I navigated the neighborhood of my memory with the actual layout of the city streets. That’s what we do with images, too: we read them as maps that confirm a memory.

In the introduction to the 2023 volume, Fattori McKenna cites Roland Barthes’ idea of the punctum of an image, the thing that grabs us: “The punctum of a photograph is that accident which pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me).” This is to say: the photographs you respond to likely have something which hooks you and lingers. McKenna contrasts this with the synthetic image:

“[The punctum] is the singular moment in a photograph - a minute detail, a subject’s position, the way the light falls - that resonates with the viewer. A common thread among the AI-generated images in this collection, we might ourselves theorize, is AI’s present inability to produce the ‘punctum,’ to ‘prick’ the viewer and draw them into the frame.”

In many ways, uncanniness is the opposite of the punctum: rather than drawing us into an immersion in the scene, the uncanniness repels us. When I look at such images, I am often jolted by their fantastic quality in ways that makes me want to, as we say, “go there” - to allow my imagination to drift into the world captured by the image. This imagination is broken by the now well-known limits of AI: the hands, the weird sheen, the distortions. Perhaps this uncanniness is the opposite of the punctum: “that accident which pricks me, but does not bruise me, is not poignant to me.” It pricks, but doesn’t linger, we don’t immerse, we’re alienated from the image.

There are a few responses to this alienation. One is to reject synthetic images altogether: to treat them as inferior forms of photographs, which adopt the form of a photograph but fail to deliver the implied immersion. Another is to lean in to the alienation of the uncanny, to create work which plays with these barriers to entry. Recently, Swedish artist Arvida Bystrom’s generated erotic self-portraits (definitely not safe for work) live in this space, where generated distortions toy with our expectations of the images and bodies alike.

It is also possible to take synthetic images literally, as visualizations of data, and to explore the representations that map the dataset to the image. In this sense, the photograph creates a kind of documentary evidence of the dataset, wherein whatever results can be treated as a kind of “scene” which emerges from the many layers of human subjectivity involved in the training process.

Another strategy might be to challenge the idea that they owe any real debt to photographic practice in any way beyond the allegorical.

Capturing the Moment

“Part of the poetry of traditional painting is the way it created an illusion that the painting depicted a single moment. In photography, there is always an actual moment - the moment the shutter is released. Photography was based in that sense of instantaneousness. Painting, on the other hand, created a complex and beautiful illusion of instantaneousness. So past, present and future were simultaneous in it, and play with each other or clash. Things which could never co-exist in the world could easily do so in a painting.” — Jeff Wall

A few minutes away from the Flickr Foundation HQ is The Tate Modern, which is currently exhibiting Capturing the Moment, which documents the relationship between painting and photography. The synthetic image can create paintings and illustrations, or photographs that resemble real life events. As a result, it is often seen as a technology that challenges the primacy of both.

But the history of art is always more complicated than big tech ever seems to be curious about. There is always a cultural negotiation with technology, and artists are always at the forefront of those experiments. The photographer and the painter weren’t always enemies. Photographers may lean painterly, and painters may lean photorealistic, but painters may also respond to the painterly photograph and photographers to the photographic painting, etc.

In some ways it makes more sense to describe AI generated images as drawing from this conceptual lineage of paintings (they represent a reality which is abstracted from any actual events), achieved through statistics and represented using digital means rather than pigments. The synthetic image then is a kind of painting that fools like a photograph, a painting that presents the illusion of time with the realism a photograph but without its integrity.

Maybe this is obvious: paintings are artificial, and so is artificial intelligence. But there is still some fun to be had there. I was struck by Cecily Brown’s work, which seems to capture a breakdown of the realistic depiction of images into abstraction through paint. It’s there in her description of her practice, and the ease with which I would be able to substitute paint with data:

“I think that painting is a kind of alchemy. The paint is transformed into image, and paint and image transform themselves into a third and new thing. I want to catch something in the act of becoming something else.”

I think the synthetic image is a kind of alchemy. The data is transformed into image, and data and image transform themselves into a third and new thing. I want to catch something in the act of becoming something else.

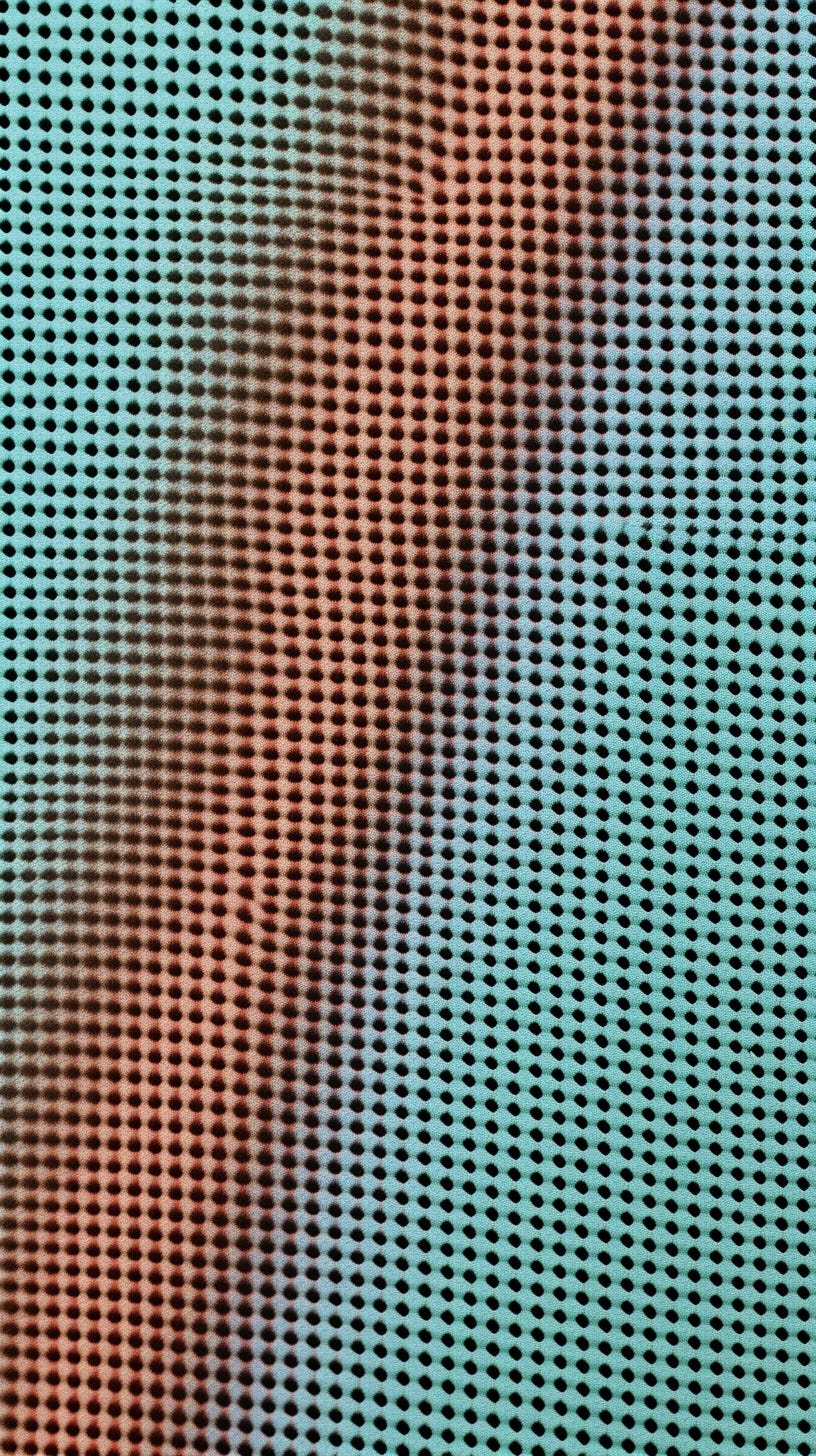

For me, it looks like the image below: the transformation of the process of constraint at the heart of a generated image system toward breakdown, ie, finding ways to erase the limits of algorithmic constraints. The image below is created by tricking the system into rendering an image of noise, which it cannot do; what we see here is process without content, a breakdown of meaning into pure synthetic representation.

I’m preparing for a talk later this month in Germany on chance operations in art and their relationship to generative AI systems, which comes on the heels of attending a conference and concert series for experimental music in Dublin where I did the same but for music.

Chance music, in the spirit of someone like George Brecht, was designed to remove the human from the process completely, so as to eradicate the bias of the human ear and find some new kind of form. AI is not pure chance either, but the constraint of bias, and breaking free of that to create “new images,” seems like a way of bridging painting and photography and some other, third thing. A digital image that contains no reference to images is, in one way of seeing it, a more accurate “photograph” of the reality of these systems than any representationally “inviting” image could ever be.

Things I Am Doing In April

London, UK: All Month!

As part of my Flickr Foundation Residency I’ll be in the city of London for the majority of April, with a few events in the planning stages in a few UK cities. I will keep you posted when dates are final! But if you’re in London — or Bristol or Cambridge — keep a lookout, or let me know if you want to do something.

Sindelfingen, Germany April 19, 21: Gallerie Stadt Sindelfingen

For the “Decoding the Black Box” exhibition at Gallerie Stadt Sindelfingen, which is showing Flowers Blooming Backward Into Noise and Sarah Palin Forever, I’ll be giving an artist talk, “The Life of AI Images,” at 7pm on the 19. On the 21st, tentatively, I’ll be part of a daylong workshop showing new work linked to “The Taming of Chance,” a project by Olsen presented alongside new works by Femke Herregraven, the !Mediengruppe Bitnik, Evan Roth & myself, who will all be there in person.