What is an idea? (or: Christmas in July)

What I mean when I say "art and technology"

I failed out of my first college art class because I submitted a board game as my final still life. Training young artists often focuses on the technical skills, so it’s not a surprise that young artists, or people who are not artists, often view art as a technical exercise.

I meet so many people who say that they “aren't creative.” I meet skilled artists who say they don't have any ideas. Part of the issue may be that we don't teach art in a way that gets at conceptual, abstract dimensions of thinking.

I'm finding that in my job search. I'm interested in how artists use technology. Too often, that’s interpreted as being interested in the technical skills artists use to build technology that makes art: like VR interfaces, video game animations, or website design. The more accurate, less employable statement is that I am interested in how artists tear technology to pieces and what those pieces get reassembled as.

For the record, the resistance to concept-driven employment doesn't surprise me. San Francisco subway stations used to be full of ads making fun of people with ideas. "That's cute," they'd say: Everyone has ideas, but nobody knows how to execute them. But isn't the opposite true? San Francisco is full of people executing terrible ideas brilliantly.

So, I've been thinking about this question a lot: What the hell is an idea? And why are they important? And I keep coming back to one phrase: Christmas in July.

We know that Christmas is not July, and yet, somewhere, the concept of "Christmas in July" emerged. It's a 1940 film, but the earliest reference is Goethe's opera, The Sorrows of Young Werther.

On the surface, Christmas in July seems like two ideas. But it’s two constellations on a collision course. Christmas has a range of associations for me: Christians, Santa Claus, Jesus, Trees, Ornaments, Snow, Candy Canes. Then there's July, which has another set of associations: Sun, Heat, Beaches, Surfing, Surf Rock, Lemonade, Bathing Suits.

By placing these concepts beside each other, you can begin exchanging those associations.

Zoom out here. You're transcending boundaries of association to recombine the things that defined those boundaries. When you do that, you create something new: for example, Santa Claus on a surf board. (This is only new in the Northern Hemisphere. In the Southern Hemisphere, "Christmas in Winter" is the novelty).

There are a few things going on with Christmas in July. First, you're moving a set of associations across time: December 25 moves to July 25. That decontextualizes some of the signs associated with "Christmas." Once decontextualized from December, we can move them around like pieces on a chess board.

For example, [Santa] [Sleds] [on] [Snow]. By removing one element [Snow] and inserting another with close-enough properties [Waves] and adjusting accordingly, gives you Surfin' Santa.

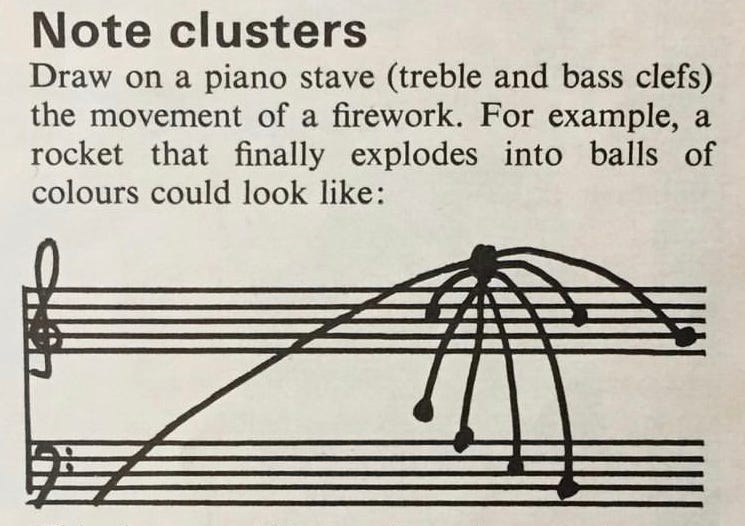

You can apply this lens to any system, from visual language to complex social interactions. Thinking about concepts is thinking about ideas in specific contexts. Thinking about those concepts is an act of deconstruction. Rearranging those deconstructed pieces in novel ways can be the result of an idea: the idea to recombine, remix, collage, etc. It can also generate new ideas by looking at relationships between existing concepts and attempting to reconstruct those relationships through other means: new icons, new metaphors, new people, new times, spaces, use cases, modes, media, etc.

In its original Greek, an idea is "a pattern." In Platonic philosophy, an idea is "an archetype, or pure immaterial pattern, of which the individual objects in any one natural class are but the imperfect copies, and by participation in which they have their being." In the 17th Century, idea got defined as a "concept of what ought to be, differing from what is observed."

Christmas in July has Christmas and July, but it also has in. In is the relationship between these concepts. And you can explore different relationships between these ideas. We know what happens when Christmas is outside of July.

But Christmas can have other relationships with July. It can mourn July. It can cancel July. It can replace July. The further you push that relationship, the more space you introduce between concepts. You can then begin to fill in that space with other concepts. A winter holiday dedicated to mourning the summer sounds relatable.

I'm not arguing that "Christmas in July" is peak art, or the Best Idea. It's a metaphor for the overlap and contradictions between concepts and systems. Words and grammar, for example. When I talk about "artistic research," I'm not talking about looking up painters in books. It's taking concepts apart not only to decontextualize them, but to find hidden connections, relationships, and contradictions.

This kind of relationship research has a lot of other names. Semiotics studies relationships between words and what they name. Systems thinking studies relationships between physical structures, nature, and people. Cybernetics studies relationships between humans and machines, and is, in the words of Gordon Pask, “the art and science of manipulating defensible metaphors.”

Technologies such as machine learning depend on understanding relationships between pieces of information. However, it understands these relationships in ways that are prescribed by the people coding the software. The insights — the “ideas,” — produced by a piece of code typically do not understand the fluidity and variety of possible relationships between the world it has recorded and broken down into individual nouns. It’s not therefore the role of an artist to invent technologies that influence our world, but to map those technologies to their possible influences. Sometimes this is called “futures thinking.”

One of my favorite attempts to teach machines about relationships comes from digital humanities. CIDOC is a 170-page catalog of possible relationships that might exist between pieces of data. (What if Christmas was at rest relative to July? Or was a currency of July?) Unfortunately, no system is currently smart enough to apply it from scratch. So humans tag these relationships, hoping that a machine learning program will eventually pick up enough patterns (ideas) to start auto-assigning the more repetitive relationships.

Again: Artists don’t have to solve these problems. They reveal them! Artists working in technology work with relationships between society and systems. They emphasize the "relationship between things" rather than things themselves, imagining new relationships and ways of thinking that elude the designers of the systems they’re working with.

To me, this shift from a technical focus to a conceptual one in technology-based artwork is infinitely more interesting as a practice. It means going deep enough into concepts to break them into pieces while preserving and reimagining links between the pieces of interacting systems. You look to find contradictions, overlaps, and relationships. You uncover the assumptions, biases, and personal stories hidden inside them. Then you put those findings together, following a strategy.

Then you build something. Or don’t. Maybe you write a paper, or go on a podcast. Art is the process more than the result. I don’t think a lot of people would call breaking TV’s artwork, either, until they did.

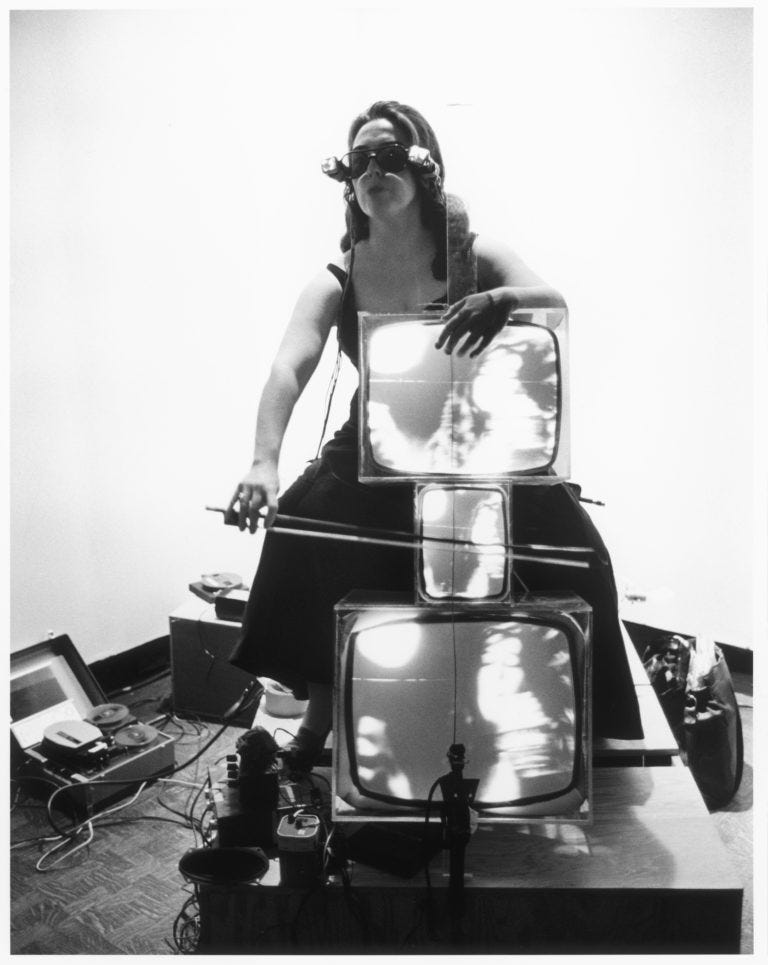

Last week I was in San Francisco watching a very old dog. I managed a quick escape to the SFMOMA for an exhibition of Nam June Paik's work. It may be unfair to boil any artist down to a formula, because "formulas" are much clearer in hindsight than when it hasn't yet existed. That's not what this is. Instead, I want to show how one could arrive at a Nam June Paik work by, for lack of a better phrase, "Christmas in July'in It."

The clearest example of this is Paik's Visual Synthesizer. A synthesizer produces sound by modulating the speed and shape of electronic pulses. Electronic visual information uses the same electronic signals. Paik's move was to dissect these two systems, and exploit that relationship and connection between them. The Video Synthesizer is the result of that.

Once Paik had that system, he was able to begin another layer of interventions and push those relationships. What if the video synthesizer was treated as a musical instrument? What can we do with video that we could not do with audio? What if we further removed the sound metaphor from the system? What can we do with its physical properties?

Each of these interrogations of the concept of "video" and "synthesizer" produces a new set of works. It ends up expanding to satellite TV experiments, costumes, live performances, and more.

I see “the artistic process” as this process of disassembling one world of perception and reconstructing it into some other form, forms that reinforce alternative possibilities and readings of the perceptual expectations of particular concepts. The result of these interrogations is art whether it's executed through a drawing, a VR experience, a piece of writing, or a lecture. Creative, critical reinterpretation of society is only synonymous with art because in other spaces, the rules and boundaries are explicit and political. There is a "way of doing things." When you step outside of that "way," you get into the idea space.

That's why it's so valuable to think about technology "as an artist." Because technology is the product of ideologies and imagination that need to extended, dissected, exposed and critiqued. When its rules and boundaries are explicit and political, people suffer and the future tightens. Expanding that space in technology reveals otherwise unseen relationships and contradictions. It holds room for bringing people in, in ways we know are desperately needed.

Things I’m Reading This Week

#

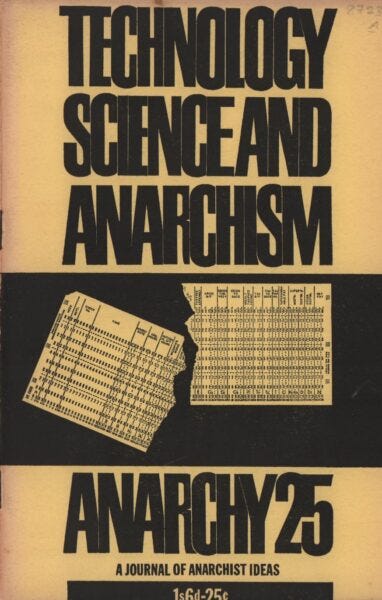

Anarchist Cybernetics

Thomas Swann

As a counter-balance to the more dominant Californian Ideology of systems-for-profit, I’m interested in the overlaps between cybernetics and alt-politics. I am unsure if any existing ideology is really nailing it, but something might come from thinking more about how tech might be built in the service of something aside from San Francisco Capitalism. Thomas Swann’s essay looks at what an anarchist cybernetics might be, finding plenty of precedent that reverses the dominant spin of Cybernetics as a centralized, top-down system of control. (Swann also has a book).

At the center of this connection between anarchism and cybernetics is the idea of self-organization, and while this was initially developed in the context of technical systems, it was applied to social systems as well. Through this, cybernetics gives us a framework for understanding how people can organize their lives collectively and without structural hierarchies of command.

#

Max Mollon: Let’s move beyond the limits of critical, speculative and fictional design

James Auger and Ivica Mitrović

A dense and provocative interview with the organizer of Design Fiction Club on the watered-down radical potential of design thinking and speculative design processes (science fiction, or futurist thinking, for example):

“There is a growing use of fiction to re-galvanise the design thinking sector, which is running out of steam (e.g. the term “future design thinking”). However, the critical potential of these practices is often eroded in the process. For when it is radical, critique through design is incompatible with the logic of profitability and growth which is the lifeblood of the design sector today—and it is incompatible with the entire capitalist system which saw its birth and supports it. So, can we live from a critical practice, other than in the artistic and academic sector? I.e. other than by being constrained to the neutralising space of the art gallery, or by betting on the long term through research and education of future generations?”

#

How cybernetics connects computing, counterculture, and design

Hugh Dubberly and Paul Pangaro

A historical look at the relationship between cybernetics and counter-culture, and how that emerges through today’s “human centered design” approaches. Also looks at what was lost in the process: a sense of conversation with the built world, not only about the built world.

[…] Alexander framed design in terms of adaptation, fit, and evolution—that is, as a process of feedback. However, design is not just steering towards a goal (as in first-order cybernetics); design is also a process of discovering goals, a process of learning what matters (as in second-order cybernetics). Pickering contrasts design as problem-solving with [an] evolutionary and performative approach: “I have always thought of design along the lines of rational planning—the formulation of a goal and then some sort of intellectual calculation of how to achieve it. Cybernetics, in contrast, points us to a notion of design in the thick of things, plunged into a lively world that we cannot control and that will always surprise us.”

That’s it for me this week. As always, please feel free to share and spread the word, and of course, I love hearing your feedback! You can find me on Twitter @e_salvaggio or click some buttons below and see what happens.