Data in Rust

When electronic data was designed to be erased by magnets.

These days I am immersed in tape. That’s the physical stuff — the brown strings usually wrapped around wheels inside a plastic shell, which I have been unspooling and respooling for reasons I’ll get to soon. It’s also the abstract stuff: the history of this weird medium, bordering on obsolescence, that has delivered so much to the history of the world.

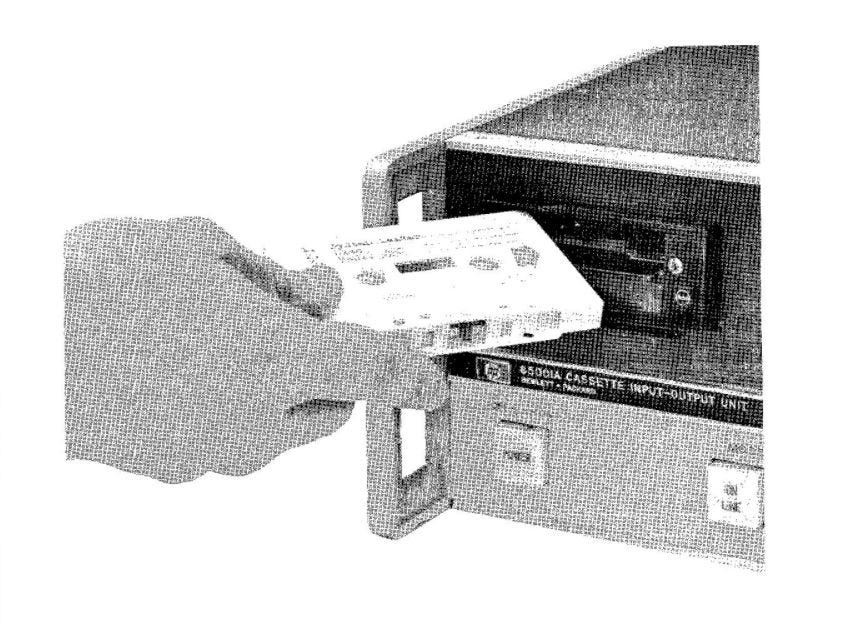

Tape was the first data storage medium, and it may prove to be the most resilient. That strip of brown plastic is actually iron oxide — rust — with positive and negative charges inscribed into them by magnets. Tape was the first step forward from punch cards, in which “ones and zeros” were written physically into paper, with light either passing or not passing through the resulting holes.

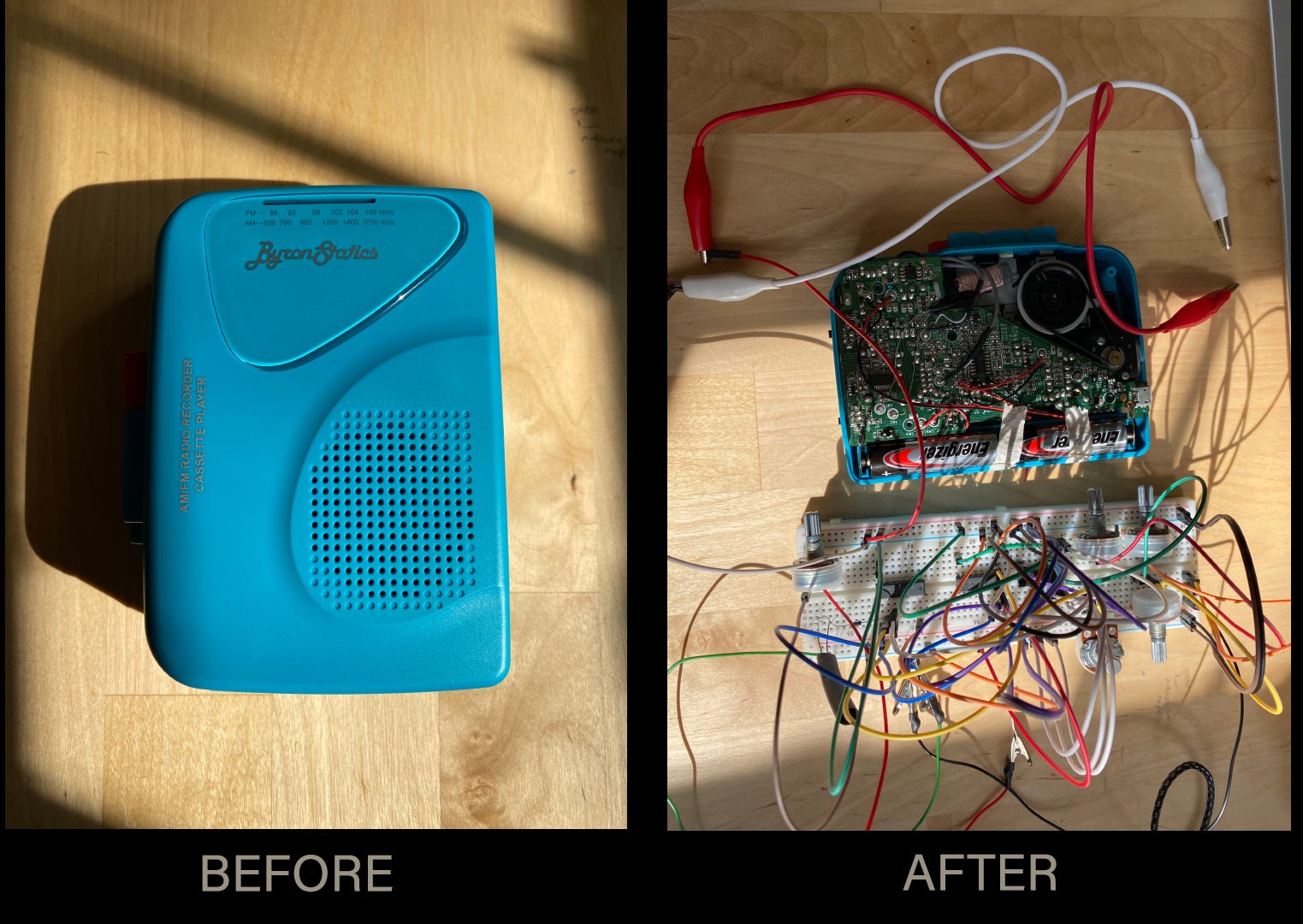

I was able to take a tape recorder apart and reassemble it into a synthesizer thanks to an online program offered up by Dogbotic Labs in San Francisco. While offering us a history of tape as a technology, they also offered up a history of tape art and tape music, framed in a way that highlights the role artists play in exploring, pushing, and exploiting the affordances of technology.

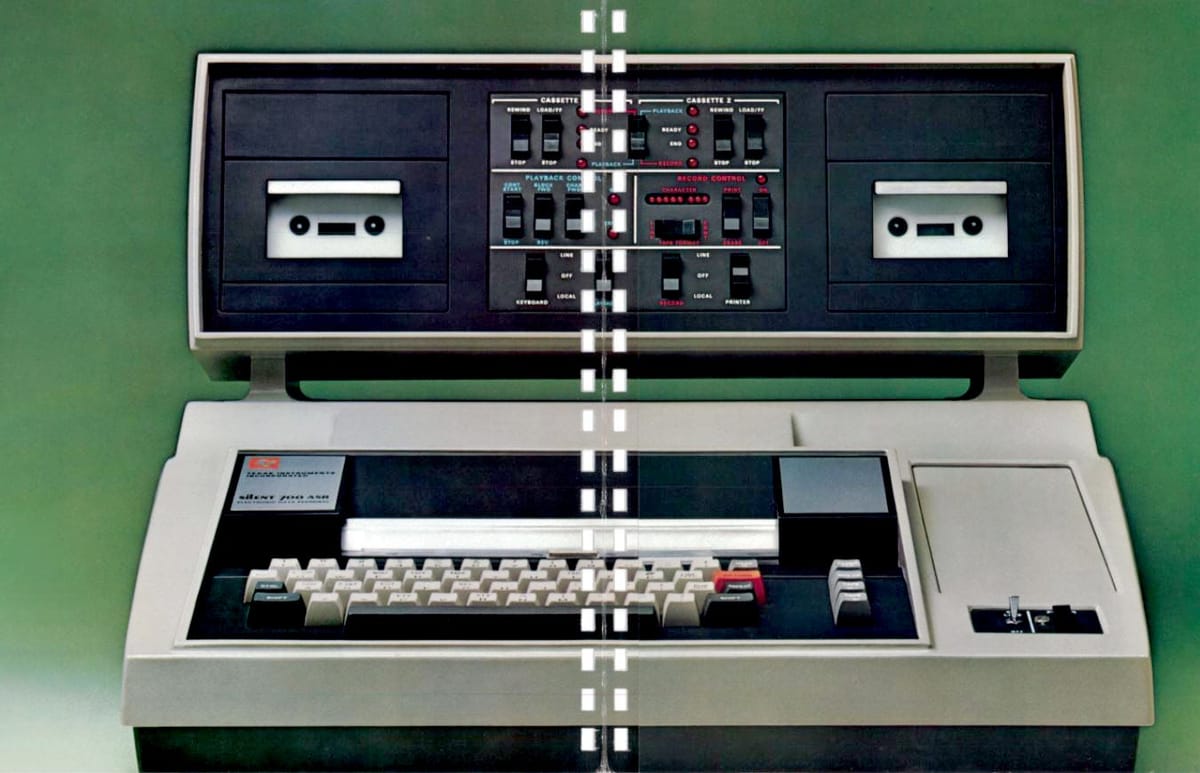

Cassettes were always a data storage device; initially they just contained voice, such as dictation. Music distribution on home cassette — especially “blank” cassettes — took off in the early 1970s, and by 1975 had inspired the use (by hobbyists) of audio tones to function as the ones and zeros of punch cards. Sound is information, information is sound.

It is also worth noting, seemingly superficially, that the early mainframe computer systems were visually indistinguishable from early recording studios. But it’s also driven a strange parallel development of music-on-tape as a way to explore the possibilities for data-on-tape. N. Katherine Hayles suggests that the first wave of cybernetics — the punchcard era, so to speak — was aimed at homeostasis: the self-maintained equilibrium of systems.

The second wave, which coincidentally (?) ran alongside the tape era, built upon that idea toward another: autopoesis. In autopoesis, feedback loops could influence one another and create increasingly complex behavior. Home recording tools, via cassette, were literally loops of information. Taking the tapes apart, splicing them, making new recordings, and altering the way tape works can also generate entry points into those loops.

Brian Eno’s “Music for Airports” is a semi-autonomous construction. The album was constructed by playing one note in a scale onto their own dedicated tape loop. The tape was cut to different lengths, then played, with each note coming in and out of phase, creating new arrangements and combinations without any interference by Eno himself. It’s all machines.

Or, of course, Delia Darbyshire, whose composition for the Dr. Who theme for the BBC Radiophonic Workshop was entirely tape spliced and slowed down — remarkably, even the bass loop you hear was one note at alternative speeds. No synthesizers involved — just cassettes and razor blades.

Finally, consider William Basinski, whose “Disintegration Loops” is a four-LP set of a single loop of tape running up against dust in a tape head. The dust was accidental, the recording was not. Over time, the dust and the particles interact, slowly deteriorating the information on the tape. It is the sound of data being erased, but also the subtle variations that occur in the process. It is hypnotic, tragically beautiful, and a self-sustained feedback loop.

Taking a cassette deck apart and making it into a synthesizer was an excellent reminder of the bits and pieces that make up a cybernetic outlook. The tape deck, once a fixed, repeating thing, now cracked open so that playback can be modulated, warped, sped up or slowed down. The essentials are the same: electricity, circuits, sensors, and information.

It’s this interaction between sounds on tape — one form of information — that creates a kind of stand-in for information of all kinds, and the ways in which information might be made to interact with other information within an open system, responsive to new inputs and stimulation from outside that system. In music, these systems can fail, and may in fact be most interesting when they do. The early synthesizer music pioneers behind the 1956 “Fantastic Planet” soundtrack noted:

The same conditions that would produce breakdowns and malfunctions in machines, made for some wonderful music.

It’s this idea that makes art such an interesting space for experimentation: it is a safe place for things to break. While the translation of music to “practical application” is more challenging, and the work of artistic experimentation happens within a sandbox, it nonetheless contributes to science and knowledge in real ways. Art is able to try things not only where the risks are contained, but where the incentives are not tied to profit or power.

What’s possible for technology then?

Things I’m Reading This Week

Coding in Cree#: Interview with Jon Corbett

Daniel Temkin

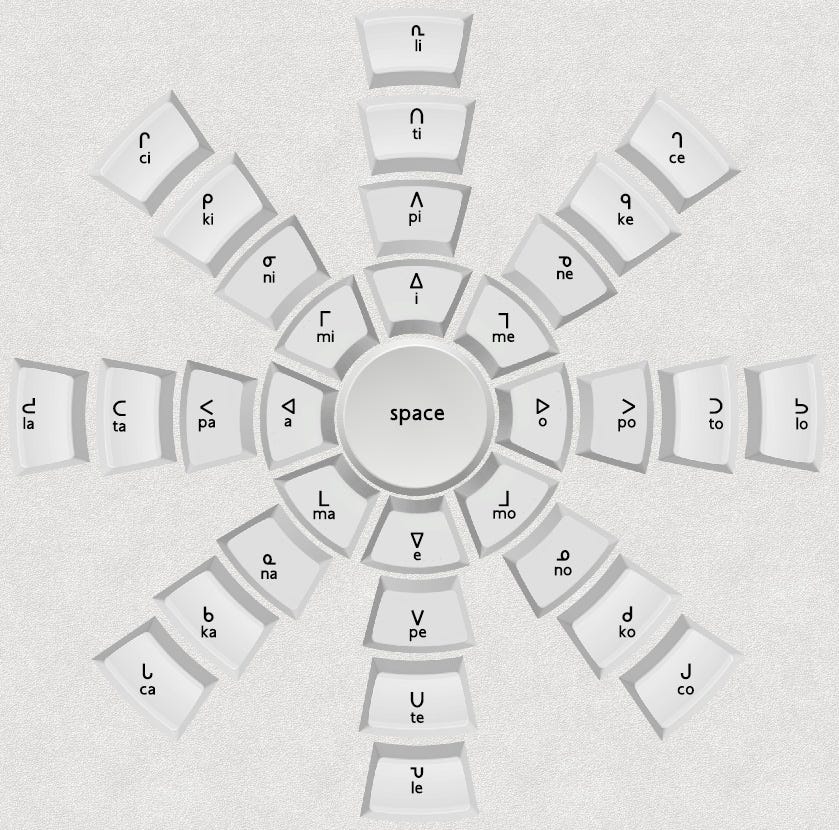

Jon Corbett created programming languages, Cree# and Ancestral Code, that “allow programming in Cree keywords using Cree concepts and metaphors.”

Modern computing frameworks (not just programming, but computing technologies in general) are often focused on efficiencies, logics, and choices that are typically not as valued in Indigenous cultures. Similarly, activities the computer does have evolved from notions of time and behaviors that don’t always reflect Indigenous concepts of “natural” orders. So an Indigenous computing framework puts into practice Indigenous concepts and knowledge. It may not necessarily change or alter the way the computer handles instructions, but it changes the philosophies used in construction and development of software and hardware.

NFTs and the ‘Art’ world: Panic and Possibility

Ruth Catlow

Ruth Catlow has been thinking, writing and curating blockchain-based work for Furtherfield through DECAL since I can remember, and has some news: the possibilities for NFTs are more complex than the money is letting on.

… for life to thrive, economies must follow cultures, not the other way round. And for this to be realised economic technologies must be shaped by, with and for the people in communities who use them—complex social living beings before rational economic decision-makers. … (To) truly be seen as “revolutionary”, NFTs and associated technologies must harness the potential for decentralisation and redistribute power and agency to more diverse people and beings, nurturing systems of healthy interdependence. And we must move away from the only story ever told about art being a story about money, because this is destroying imagination and creativity right when we need it most.

The Algorithmic Concept, 1648-1950

Mingyi Yu

This (sadly paywalled) article asks why we define algorithms the way we do, how that definition came to be, and what it prevents us from seeing.

This essential accord maintained over a sequential and step-based nature of algorithms only attained prominence relatively recently, contemporaneously to the emergence of computer science as an academic discipline. … This particular conception has since served as the unquestioned and defining basis in discussion of anything algorithmic. It has perhaps even become difficult to envision an algorithm as anything but an ordered series of if-then statements, a failure of critical imagination. … This reorientation was not the inevitable culmination of a grand intellectual trajectory, but the byproduct of mundane and inconspicuous administrative resolutions regarding nomenclature.

The Lucas Plan: What can it tell us about democratising technology today?

Adrian Smith

A fascinating account of an ahead-of-its-time social movement. In 1976 a group of Aerospace Engineers put forward an idea: that the UK government should fund local, community-driven innovation & design programs. It was rejected.

The movement that emerged challenged establishment claims that technology progressed autonomously of society, and that people inevitably had to adapt to the tools offered up by science. Activists argued knowledge and technology was shaped by social choices over its development, and those choices needed to become more democratic. Activism cultivated spaces for participatory design; promoted human-centred technology; argued for arms conversion to environmental and social technologies; and sought more control for workers, communities and users in production processes.

Music Against Fascism: DIY Versus the Right Wing Safety Squad

Ben Harley

I love what this paper says and how it was written: a paper on cultural rhetorics that isn’t afraid to embrace its own subjectivity. (Sadly paywalled).

Five days after the Ghost Ship fire killed 36 people in Oakland, CA, a group of 4-Chan users calling themselves the Right Wing Safety Squad began a campaign to shut down similar do-it-yourself venues that they saw as “hotbeds of liberal radicalism and degeneracy.” This essay argues that these venues were targeted not simply because of their politics but because the embodied practices of music-making that occur there—performing, dancing, singing along, applauding, and having fun—have the potential to create community across perceived differences. These kinds of communal connections are a threat to alt-right ideologies that leverage difference to keep people frightened of one another. Taking cues from cultural rhetorics, I embrace my identity as an old scene kid in order to share my relationship with underground music scenes, tell the story of the alt-right’s campaign, and discuss the significant role music-making practices play in creating underground communities.

The Kicker

I was delighted to learn of this early (1944) experimental music piece by Halim El-Dabh, who used a wire recorder to collect field recordings of a market in Cairo, and then altered the wire with reverb and other radio station effects fodder. It’s a strange, ambient piece of music that is often overlooked in our histories of electronic music.

It’s been great to see the steady flow of new subscribers, welcome! I hope you enjoyed the newsletter. If you did, I encourage you to share it far and wide, as it’s a labor of love with chiefly word-of-mouth circulation. And if you’re just finding it — you can subscribe with the button below. Cheers!