Feline Rock Bands and Other Wicked Problems

The cats are trying to design music and need our help

Some years ago in Portland, Maine I attended a performance of cats playing rock music. The Rock-Cats were a touring company in a small church theater downtown. There were several instruments on the stage — I recall a guitar, keyboard and drum set — with special modifications to make it easier for cats to perform them. Each cat was brought on stage one by one for a small solo showing off their talents, some of which were acrobatic feats.

Each of these sessions, as I recall, escalated in complexity and scale of fiasco. The cats were lured into strumming guitars or pushing drum pedals with chunks of tuna and clicker training. They occasionally wandered into the audience, returning only on their own terms.

It wasn’t a failure. Fiasco was the point. It was a kind of performance where tensions took center stage. The failure of the performance was the performance. When the cats did share the stage and play all instruments at the same time, it resembled a spinning-plates performance by the trainer, running from cat to cat to see how long the cacophony could be sustained. It was the best, worst concert I’ve been to.

The Rock-Cats act came to mind recently during a workshop at RSD10 on “Alternatives to Taming Wicked Problems” created by Ben Sweeting, Sally Sutherland and Tom Ainsworth.

Taming Wicked Problems

Wicked Problems have a specific definition, coined by UC Berkeley design theorists Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber in a 1973 paper that reads as if it were written an hour ago. Looking around at the failures — and emerging distrust — of experts in planning, they asked why the things that improved public health, policy and industry weren’t working for bigger problems, despite all that had been learned.

Planning had to shift, they argued, from asking what’s inside a system to what pieces of a system do — a system of nouns had to be understood as a system of verbs. Nouns you could replace. Verbs, not so much, at least not when those verbs are coming from uncontrollable nouns — as in when cats run from their assigned bass solo to the lap of a paying attendee.

“We are calling them ‘wicked’ not because they are ethically deplorable problems. We use the term ‘wicked’ in a meaning akin to that of ‘malignant’ (as opposed to benign), or ‘vicious’ (like a circle), or ‘tricky’ (like a leprechaun) or ‘aggressive’ (like a lion as opposed to a lamb.” (Rittel & Webber 1973).

Orchestrating a cat-only rock act is a wicked problem, though not a very important one. But get ready to really ride this metaphor. You can train cats somewhat, but no amount of tuna will get them to perform “(They Say It’s) Your Birthday.”

Imagine the performance as a metaphor for a massive crisis: climate catastrophes, poverty, crime. Each cat represents one piece of this problem. You can focus on one cat at a time, or you can focus on all cats at all times. But then what do you do? What persuades one cat to perform may not work for another. You have to control external noise and audience members too. And if you screw it up, the performance is ruined, the cats get traumatized, the audience gets bored.

For Rittel and Webber, wicked problems can’t be solved unless you know the possible outcomes in advance. The risk is too great, or there’s irreversible harm in trying something that doesn’t work. You might try to experiment, but scale won’t let you, because of technical, but also ethical and social constraints.

Rittel and Webber write that any attempt to solve the problem requires defining the problem, and any attempt to define the problem will be through the lens of a possible action. Climate Change, for example: the solution might be “reduce carbon emissions.” But now you have at least 2,000 problems. But it’s not just scale. You could solve 2,000 problems. But you also have to understand the relationship between those 2,000 problems and 20,000 more problems, such as who pays for it, who goes first, who resists it, what makes them resist it. Untangle one and a bunch more spill out.

If you focus on one aspect of the problem — a single cat, which is what the wonderful human conductor ended up doing, one cat at a time — is managing a problem rather correcting it. Sometimes that works. But the cats still disappear when the tuna does. Getting all four cats to briefly harmonize is an enormous amount of energy for a temporary fix that defies the actual conditions of chaos.

C. West Churchman wrote a response to a Rittel & Webber lecture on Wicked Problems back in 1967. Slicing off pieces of the problem to solve, he wrote, “tames the growl of the wicked problem: the wicked problem no longer shows its teeth before it bites.”

The concern with “taming” wicked problems is that it’s only one way through them. In the case of existential risks — climate change, racism, artificial intelligence — we of course want to tame and reduce, and tackling that complexity through a structured parceling off into distinct but related problems can help us resolve them. But, as Ben Sweeting noted in introducing the workshop, “neither lions nor social problems are amenable to taming.”

Framing Wicked Problems

This brings us to frames. Within a complex tangle of interrelated problems, slicing off a few pieces to focus on is a restriction of the frame. It’s a sensible strategy, but much goes on beyond where you’re looking.

Cats are the individual elements of a wicked problem that cannot be controlled, but could perhaps be managed. What is useful about the Rock-cats is that the design of the show imposes a frame on the chaos. Cats running loose in a church basement would not be as entertaining. The Rock-cats are introduced as a “cat rock band,” which is one frame put on the problem of cats running loose on a stage. The pleasure comes not in the futility but in the promise of coming together balanced against the risk of falling apart. It’s a pleasurable tension.

But it also, as you may notice, changes our relationship and expectations of the cats. The cats “fail” to play music, but that’s our expectation, not theirs. The system wasn’t designed for that, so the failures are inevitable. (For the record, the cats are treated well and raise money mainly to rescue other cats).

You could imagine a design expert or systems engineer coming in to see the Rock-cats and offering tools for optimizing the performance. An optimized cat band would be a very different entertainment proposition. The cats would be tamed, but the performance would be different, more standardized to a specific frame of “music” and “theater” and “talent.” It still wouldn’t be the cat’s idea.

While this example is silly, and fast approaching its limits as a metaphor, it shows us how attempts at “taming” complexity can reveal dynamics of power, even erasure. Consider the example of public policy planning, or community led design sessions, in which there are polarized positions about what needs to be done. Through one lens, you can “tame” the problem through erasure: don’t invite the activists, or don’t invite the builders. In each case, you have solved tension, but not the underlying problem. You can do this through the subtle manipulation of frames.

When design researchers bring a design “goal” to a social problem, they are buying into the idea — just a bit — that “the cats are trying to design music and need our help.” That is the wrong way to think about problems. If the design is the goal, then the process of reaching that goal is likely to flatten obstacles, rather than navigate tensions in ways that allow them to co-exist and propel things forward.

Planned Forests

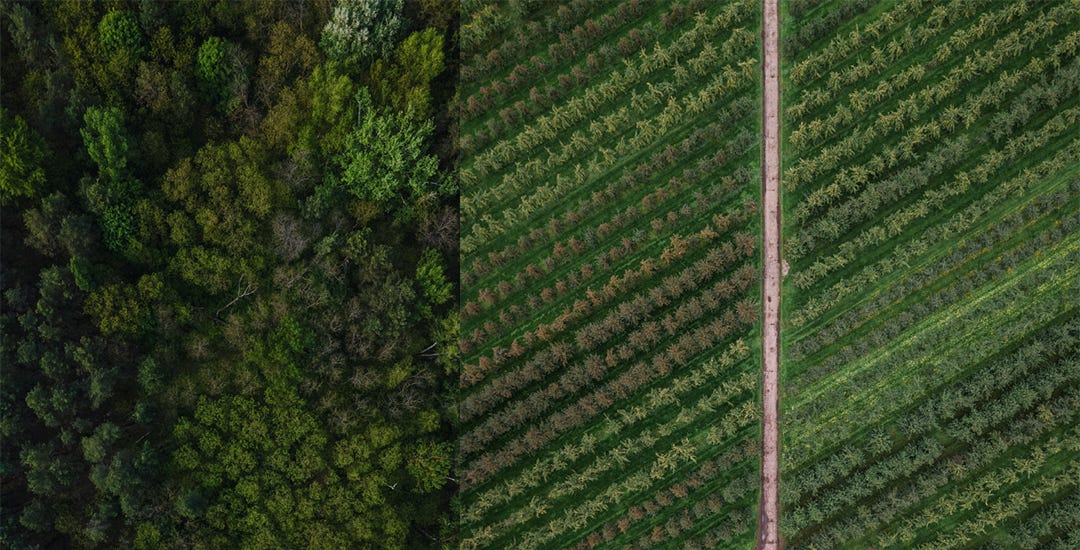

One example of taming a management problem, at the expense of solving the actual problem, comes from the world of forestry management.

In many parts of the world, the wildly disordered ground-cosmos of the forest has been colonized and replanted in orderly rows or dense clusters. But planned replanting doesn’t achieve the same ecological — or even timber-quality — results as ancient, unruly, natural growth forests. It reflects our desire to manage, to tame, to order that transforms the world into something manageable but without any sense of original purpose or function.

Today, “wicked problems” are often tackled through digitization: unmanageable forests of information parceled off and rearranged so as to be acted upon and “made useful.” Perhaps this helps us in some cases. The process would benefit from some self-reflection about what boundaries we leave in place. Who defines, manages, and “tames” a wicked problem, and where does that expertise come from? What desires are these processes in service of? Who decides what to tame, and what might we leave untamed, if we could?

If the tensions reflected in the information stored in digital databases are reduced to small parcels of mown grass, or as orderly rows of trees arranged to be quickly harvested, then what have we killed off? In person, conversations take different forms. They are not assessed by algorithms for delivery to those most likely to be inflamed by it. Nor do you filter off tensions emerging from conflict. These cats ought not to be “managed” for the benefit of a more harmonious performance.

An alternative to this is evident in critical, and self-reflective, approaches to systems thinking: understanding that the cat is its own problem, connected to the rest of the problem, and that for the cat there is simply no problem at all. It’s the work of systems thinking to engage these tensions between “problem definitions” and “solutions.” You have to look at the entire system, in all its multidimensionality, understanding that even the definition of the system is going to impose constraints that will be upended.

Away from the cats, this means embracing and seeking out situations of friction, social tension, and unease. Whereas harassment, harm, and violence are certainly unacceptable, attempts to minimize the “discomfort” of dialogue has a tendency to be designed by folks with power to build walls against the sound of protest and complaint. What we “tame” is a political process, not a design process, and any way of solving a wicked problem needs to be able to synthesize the two.

Things I’m Reading This Week

Lots of reading on tech colonization this week as I’m trying to think through an art project. While cats are a good metaphor for a wicked problem, the real ones can feel pretty bleak. The readings below are dense but well worth the time if you’re at all curious about the relationship between tech, the environment, and exploitation of workers globally.

###

The Extractive Circuit

Ajay Singh Chaudhary

Accounts can often make it seem as if capital hovers about the Earth in almost ethereal form. But the extractive circuit is not a metaphor. It works through real people, specific geographies, economically strategic areas organizing, linking, and connecting our global human ecological niche. … But whether one is committed to somehow keeping the system in motion in perpetuity or to hold on until a “cash-out,” the extractive circuit, and its maintenance, one piece of it or another, currently has your fealty. It is the exhausted world—the climate—capitalism built.

###

Digital colonialism: the evolution of American empire

Michael Kwet

We live in a world where digital colonialism now risks becoming as significant and far-reaching a threat to the Global South as classic colonialism was in previous centuries. Sharp increases in inequality, the rise of state-corporate surveillance and sophisticated police and military technologies are just a few of the consequences of this new world order. The phenomenon may sound new to some, but over the course of the past decades, it has become entrenched in the global status quo. Without a considerably strong counter-power movement, the situation will get much worse.

Thanks all for reading! If you’ve stumbled on this post, do feel free to subscribe — it’s free, or $5 a month if you’re feeling generous.