How to Learn Like Humans Do

What it Means to Believe AI Makes Art Exactly the Way People Have Always Made Art

Sometimes people ask me how humans made art before artificial intelligence made art for us. I often assure them that there’s not much difference at all: AI was designed to learn the way that humans do, and to make art the way humans once did.

This shouldn’t surprise us because, as we know, AI models are precise replicas of the human brain. Lucky for us, the human brain only works in one particular way, which makes it very easy to replicate a universal, human way of thinking.

The same is true of art. There was only one way in which art was made by humans: a precise, clearly defined process. When AI came about, this process was easily automated with very minor translation between biological and digital processes.

So when people ask me how AI makes art today, I confidently assure them that it learns to create art the exact same way that humans do. But to quench your curiosity, here is a short description of the way humans made art, before we opted to let AI make it for us.

Artistic Process Step One

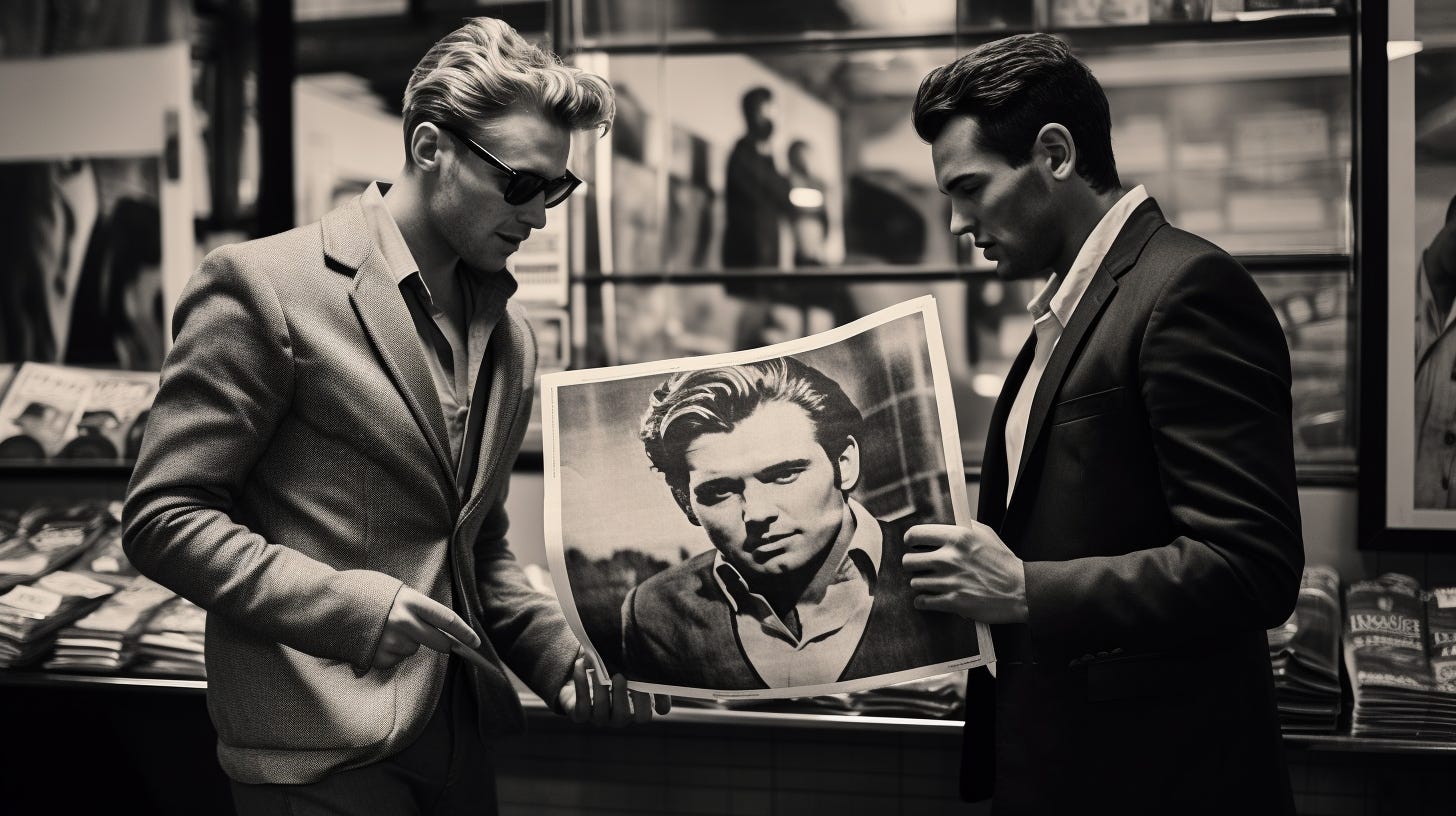

Artists would gather up their friends, family, and members of their community and task them with finding existing pictures of all kinds. These people became Inspiration Agents (IA) and every human artist required them to make work: the more IA you had, the faster and more accurate your creativity would be. More powerful artists had many, many IAs at their disposal.

Today, this has been replaced by generative AI — a democratization of art making.

Artistic Process Step Two

Each Inspiration Agent was dispersed to travel the world in search of as many images as they could find. This needn’t be a preoccupying concern: a few hundred thousand each would do. For every new picture they found, the Inspiration Agent followed a special Creative Process using tools developed by museums and institutions and available via monthly subscription.

Today, this step of human creativity has been replaced by Diffusion Models, which are far more efficient. Bots crawl the web, looking for images and captions: artists no longer need to send hundreds of people on expensive quests, and no longer have to pay the art world expensive monthly fees for the ability to make art. Instead, they can pay AI companies — making art accessible to everyone for the first time in history.

Artistic Process Step Three

You might think that this was enough. With all of these pieces collected from various sources, there must be enough material to create new images, right? Wrong. Simply using these images is not creativity. Instead, artists had to learn from them.

IAs looked for a description of the image, and determined which part of that description might describe parts of the image. They could only do this by comparing what they were looking at to other images and descriptions that they had collected — no cheating!

Relying on personal knowledge or understanding of the world to interpret the meaning of the image was not part of the creative process. IA’s saw nothing but the lines, colors and shapes, inch by inch on the image, and determined how they fit together as numbers in a grid. They labeled a box with the key pieces of the image description, cut out the pieces of that image, and placed them into the appropriate box. Now they had a text-image pair from which the art would be made.

Today this is done by tools like CLIP, which automatically connect clusters of pixels to specific text information and store it in a dataset — just as humans have done in their homes since the time when our homes were inside caves.

Artistic Process Step Four

The artist’s Inspiration Agents met at a colosseums, conference centers or art studios and compiled a list of the words they encountered. They then determined the likelihood that any particular shape, color, or line type would appear in the vicinity of that word. They combined boxes with similar terms so that any image that fits those precise terms could be clustered together.

This is now achieved through a link between CLIP and the diffusion model, which was built to serve as an exact replica of how humans have always made art. That is why it so neatly aligns with the long history of massive collective conferences and the statistical assemblage of collected images that have been the backbone of human culture since the first cave paintings.

Artistic Process Step Five

Each box was opened and every cut-out image was laid onto the floor with a massive sheet of construction paper. Every Inspiration Agent spaced out the images on each side of the sheet. Every foot or so, they would redraw that image with a slight change that made it look like the next closest image. When the sheet was full, they rearranged those images and drew these variations. They would tabulate these variations into a mathematical equation that could describe commonalities between shapes, colors, boundaries and curvatures closest to the two starting points.

That information went into an artist’s library, a collection of books stored in a massive building that was filed by key words. Today this is known as the latent space, where every variation, in multiple different parameters, is waiting to be activated when a user enters a specific prompt. Back then, you would have to hand your prompt to a person on a piece of paper, who would take it to a library to start production!

Artistic Process Step Six

Once all of the images were mapped out on the giant piece of paper, and their correlations described in books with precise instructions for their reproduction, the original collected images are destroyed by being placed into a carefully sorted archive that remains accessible at all times. You might think that this is not the same as destroying the images, but it is, and you just have to believe that.

No one would ever talk about those source images again, and if anyone claimed that they “created” one of those images in the archive, they were simply told to respect the artistic process. The widespread understanding that all art was there exclusively to be reinterpreted by others is why there has never been any interest in protecting rights to people’s original ideas or labor. Because all art was always given away for free to be used and remixed by others, artists were simply paid by either the government or the public to live and make work.

Exactly as it is now.

Artistic Process Step Seven

Now the artist sets about to work. The artist writes a message on a piece of paper for the Inspiration Agents to ferry back to the library. The genius of the artist is soon to be rewarded.

This is what the Prompt replicates.

Artistic Process Step Eight

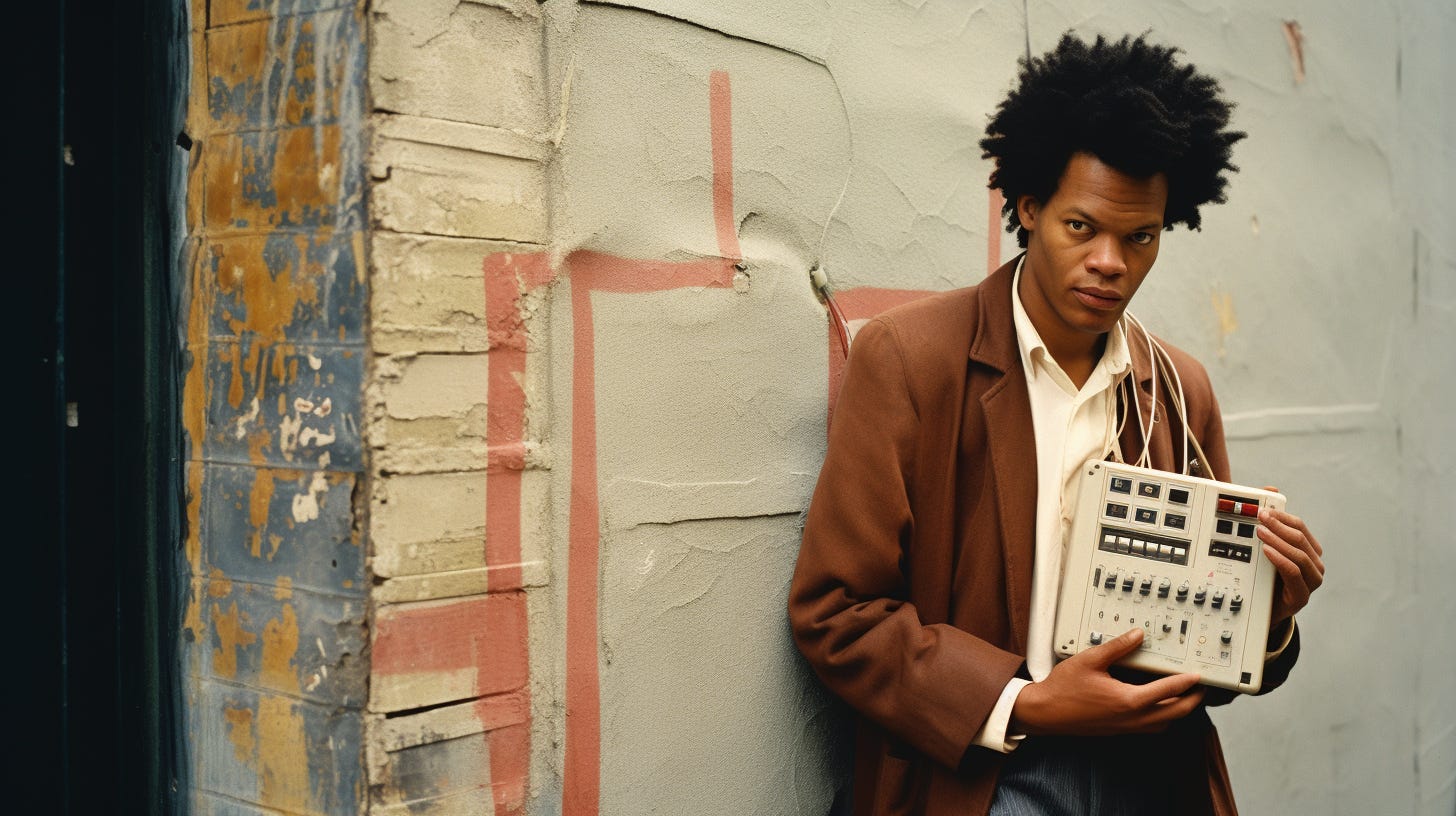

This message is taken by an Inspiration Artist to the library, who looks up the words in the prompt for the corresponding category among the many shelves, assembled in the earlier stages of the process. Remember that each book contains a loose outline of the shapes, lines and colors most commonly associated with the images they had gathered.

Meanwhile, another IA prepares options for the artist by throwing random paint at canvases until there is no white space left. Using only the books to guide them, the IAs look upon these canvases, and look through the pile of books. They try to match the patterns of the random paint splatter with the outlines and shapes in the books for each word, scraping the paint away to highlight the shapes that they find. Each time they scraped away some layer of paint, they would scour through the books anew to find new directions for removing the next layer of paint.

Today this is automated in the removal of noise from an image of pure noise. Diffusion models are able to remove noise and cross reference to these “books of patterns” in a matter of seconds, while artists could take years to find results this way. As you see, AI has changed nothing of the artistic process except for its duration.

Artistic Process Step Nine

The Inspiration Agents repeat this process four times, offering four different results for the artist to choose from. The artist selects the one they like best, and then shares it with others, telling them that this work was the result of deep thinking about how to describe this particular piece to the IAs. Or, they can refuse all of those works and send the IAs back to the library to create four more. Some artists, such as Georgia O’Keefe, generated thousands of prompt outputs before finding her signature style, many of which were censored before they could even leave the library.

In Conclusion

The steps of the artistic process, simple as they are, were once the work of countless elite, gatekeeping librarians and art students. Today these institutions have been replaced by Generative Artificial Intelligence, a result of close study of the human creative process by Venture Capitalists who have hired many experts in the programming language, Python.

These Venture Capitalists painstakingly translated their love and knowledge of the artistic process into algorithmic models. They even brought the art world into the process of developing these technologies, by replicating it in the form of remote, low and unpaid labor, the collection of vast amounts of images into datasets from global sources, and their selfless goal of developing extremely large, powerful systems that could rival the vast infrastructure of the art world and free artists up to do work they really enjoy, such as manual labor and data entry.

This freed us from the tyranny of effort and attention that was inherent to craftsmanship, allowing the timeless method that artists used to find inspiration and express themselves to be automated.

Mary Oliver once articulated the great problem of inspiration that has made art so unreliable as a service for centuries. Her messy, unclear definitions of artmaking, as in the following, show all the painful steps that have been removed from the process of artmaking:

“No one yet has made a list of places where the extraordinary may happen and where it may not. Still, there are indications. Among crowds, in drawing rooms, among easements and comforts and pleasures, it is seldom seen. It likes the out-of-doors. It likes the concentrating mind. It likes solitude. It is more likely to stick to the risk-taker than the ticket-taker. It isn’t that it would disparage comforts, or the set routines of the world, but that its concern is directed to another place. Its concern is the edge, and the making of a form out of the formlessness that is beyond the edge.”

In sum, AI makes art just like we do — but without all of the messy inefficiencies, trial and effort, and attention to personal meaning that distracts us from achieving examples of a pure, universally accessible image.

Gratefully, that kind of inefficiency has been removed from the artistic process through automation. It puts to rest the myth that the work of the poet, the painter, the musician or any free spirit is to articulate the messiness of one’s internal emotions into a more broadly accessible plane.

Today, us sober and rational folks know the work of an artist is just this: to select the best of four options generated by an independent analysis of a massive library containing mathematical translations of geometries and other patterns associated with words used by others to describe those images — just as it always has been.

Look it’s the internet so I want to be clear that I’m kidding here. So, if you enjoyed this post feel free to share it and follow me on social media to let me know what you thought. If you didn’t enjoy it, God knows you’re going to do that anyway. I’m on Blue Sky as eryk@bsky.social or find me on:

You can also share and subscribe to the newsletter!