I Was a Teenage Net Artist

Zen and the Art of the American Standard Code for Information Interchange

I was in high school in 1997, and had my eyes set on Hampshire State College. The application essay prompt asked me to compare two distinct artistic periods. I submitted “Zen and the Art of the American Code for Information Interchange,” which connected Zen, Japanese calligraphy, and internet art. Specifically, ASCII art, the use of text characters to make images. You can shade the characters in different colors, or you can use specific brightness values — a full stop (.) will be less bright than a pound sign (#), for example.

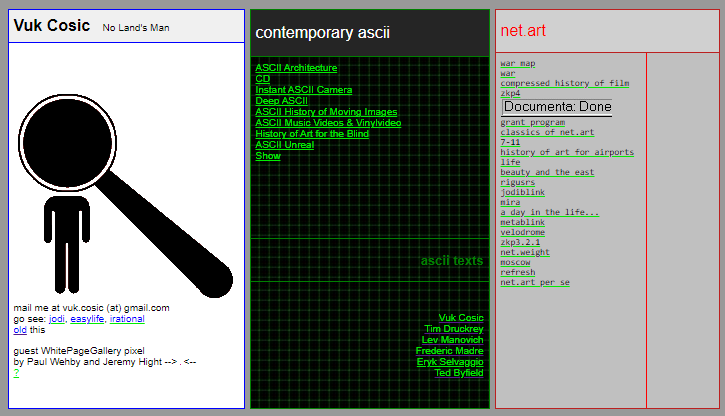

The essay was edited by my high school English teacher. It wasn’t very good. Hampshire rejected me. I remembered it recently because I noticed a link with my name (misspelled) on Slovenian net artist Vuk Cosic’s website from the 1990s.

I went looking for this essay on old hard drives, which ended up being a deep dive into my past work. Most of that work was taken offline around 2005, and a lot of it simply doesn’t run. Net Art relied on internet browsers, HTML code and other things with evolving standards. I was leaning into glitches and exploits that are obsolete. Even text looks different.

Last week I opened up the files I could find and recorded the result. In this week’s newsletter I am sharing an assortment of work I made from the late 1990s through 2006.

I was an untrained artist during this period — I graduated from high school, but had flunked out of college after one semester, having stopped going to classes to focus on making art. At the same time, I was being invited to academic and activist conferences and working as a VJ at music festivals. My writing, which I’d post to mailing lists, was being republished in European magazines and has shown up in a bunch of people’s PhD theses.

For the most part I had no clue what was happening. I was a disorganized kid who resisted institutions and suffered from undiagnosed depression and anxiety for most of my early adulthood. I’ll get into that a bit here too.

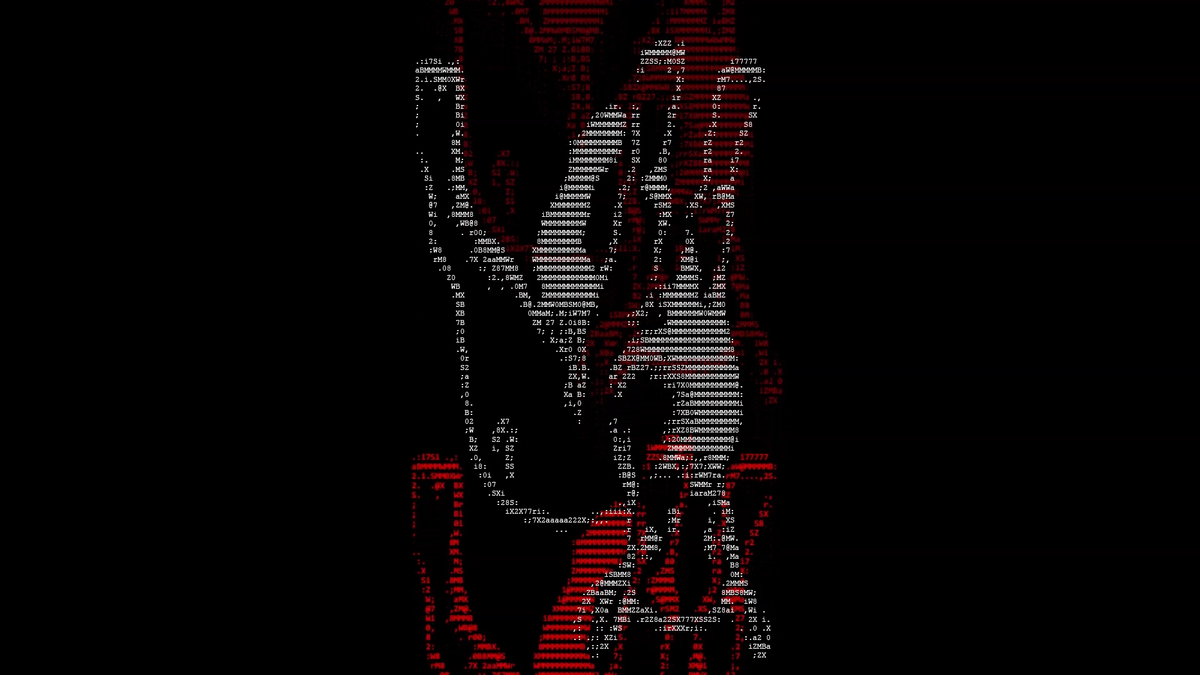

This is the first time anyone has seen any of the work I was making since I took it offline 20-something years ago. Below is one of them: a glitching html and ASCII work meant for a browser window. I don’t remember when I made it. I’ll get to all this in a minute, but first I want to talk about that Zen & ASCII essay.

Zen and the Art of ASCII

The essay wasn’t great, though I was surprised to see that I was citing folks like Ted Nelson while writing about Vuk Cosic in high school. On the other hand, I also heavily cited a comic book called “Zen for Beginners” — though I think that’s defensible.

I sent the essay to Vuk for a collection called “Contemporary ASCII,” where it did not appear. Vuk did put the thing on his website, alongside the other smart writers like Tim Druckery, Frederic Madre and Ted Byfield. My name was spelled wrong, but it was me. The essay has been a dead link on the site since at least 2001. The earliest version of the page isn’t available at the Internet Archive, though I did find that the text was just cited in a 2023 book about typography from MIT Press.

Re-reading it, I am wondering if taking it down was an act of kindness. The ending was alright though, and I’m putting it here because there’s a lot of pointers in that essay to where I am now, 27-odd years later:

… [we can] begin to see the peculiar spiritual essence of ASCII art as the elimination of the logical values of letters. Linguistics are shunned. Words are abandoned as meaningless, and punctuation is used chaotically. Letters stutter across the page in the completely absurd descriptive narrative of an image, rather than the intended use of "Information Interchange." The recycling of the alphabet as a basis of language, towards the creation of what the letters were meant to describe, creates meaning within the lack of meaning. The image, which renders the alphabet temporarily useless by its superior descriptive power, is based on the relics of words. As a paradigm shift, it is a perfect example of the interplay between the world of [perception] and that of description. Only through the breakdown of the written language can we express an image with more clarity, a sort of digital vow of silence, or the Internet speaking in tongues.

It was an observation about the internet, and internet art, that I could have written, with some adjustments, about AI generated images today.

But I was a teenager, and it was 1997. In that essay I see reflected a deep frustration shared, perhaps, by many teenagers. There is a total distrust in language’s capacity to express anything meaningful about myself or the world. Most of my work from this time — music and writing and art — was drenched in the tension of trying to say something, but feeling like every arrangement of words was hopelessly banal and bound to be mediated into trash. I was angry at the injustices I saw, but because of my depression and anxiety issues, any expression of outrage felt clumsy and unearned. It felt stupid — “angsty” and “irrational.”

By 1997 I had started writing to a handful of these media theory and net art mailing lists — Rhizome and Nettime and others. I don’t blame people for not taking me seriously. I can’t hold it against anyone, but the reaction to my presence was pretty rough. I remember literally being used as an example of “banality” by academics who thought any engagement from artists with politics was boring. It is true that my politics were pretty naive. In hindsight, though, this hostility came from people who have never given a second thought to the role power plays in art, or media, or technology. People could use “rational” and “objective” terminology as an excuse to ignore that, even belittle people for thinking about it.

Today I see that those people — a small subset of career academics and anonymous trolls — had put me into a box at the same time that they took away any tools to escape that box. But I also perpetuated what I’d internalized. In hindsight I realize I reacted pretty naturally as someone who was exposed to elements of toxic academia when I was 15.

I watched as people would weaponize academic arguments, and much of what I learned in those environments was how to mask personal hostility as reason, how to make someone you didn’t like look profoundly stupid with theory. It was, often but certainly not always, an intellectualized street fight. I was also, already, an anxious teenager. The combination made me an even more defensive, often belligerent and self-righteous troll responding to that toxic environment online by matching its tone. It was not the source of my problems, but it offered an environment for me to normalize and wallow in those problems, and learn a set of terrible coping strategies.

An insecurity still lingers inside me as a result. It took years for me to acknowledge that the pleasure of art theory and media theory and cultural theory was that they were theories. A way of making sense of things. An idea. And like all ideas, theory is more vibrant and interesting when it is diverse, and loose. There is no use in asserting one’s own theory as “correct,” or engaging in combat over it. Despite the relentlessly toxic, male-dominated mailing list culture of the time, these moments could still come through.

In that light, the net art and media theory lists of the late 1990s were also good. It was the source of my education. I was also drawn to media art and the Internet because there were many kind and interesting people involved in it. When it wasn’t hard, and I wasn’t merely taking on and reflecting its toxicity, it revealed a richer and more complex world.

For the record, anyone I name in this bit of text was great. I don’t care to memorialize the small tyrants that formed a small but loud minority. I have to be very clear that at times, I was an asshole too. I don’t think anyone should expect me to catalog that, but I regret my role in perpetuating the negativity. I should have done better, and I hope that, in the years since, I have.

I also had a life on the other side of the keyboard.

We Were 138

Behind the screen, I was hanging out with a punk graffiti scene, one that embraced queer and trans and agender kids (but never really used those terms). The Pit Kids were the punks and art students and homeless kids who hung out at the Harvard Square T stop (the “pit” was recently dismantled and redesigned). The graffiti crew was called 138, a nod to the Misfits (“We are 138”) and to the sci-fi dystopia of THX-1138. The first page we made was a satirical Boston MBTA website about how to do graffiti on the subway without getting caught.

I was a straight kid from the suburbs who found a place I belonged, which was a scene full of humans who felt they belonged nowhere. But I only hung out on some weekends and summer holidays. Mostly I connected to it through America Online. That first website was set up to document the art being made by some folks from the scene, a mashup of Situationist graffiti and Fluxus performance art infused with sci-fi dystopia, Buckminster Fuller and anarchist politics. I read a lot of Guy Debord and remember hearing a lot about Miranda July.

The World Wide Web created the opportunity to make art — and political statements — that could be seen by anyone in the world. The art and theory crowd of the Nettime mailing list — and its weirder offshoots, like 7-11 — was a radical scene, with a lot of people connecting to each other in ways that would have literally been impossible in 1993. This revolutionary rhetoric about information and connection, the sense that all of us misfits could find each other, combined with my youthful optimism made it seem like the world was on the verge of actually being changed forever.

The website was hard to run as a collective project — it was tough to scan things, tough to document what we were doing, and we had an anarchist bent that resisted archives and documentation anyway.

But what I loved was writing code that didn’t work but still did something, or made people confused about what it was doing. I started putting up deliberately malfunctioning html, linking to random Real Audio streams, trying to think about place and space and code and interaction. The Web moved from a place to build a portfolio to a place that had its own weird language, and I wanted to fill it with typos.

The Web moved from a place to build a portfolio to a place that had its own weird language, and I wanted to fill it with typos.

A moment I think about often is a small role I played during the 1999 war in Kosovo. I was a kid in the basement of my parent’s house, but I had a website. I used that website to set up Real Audio streams of a pro-democracy radio station, B92, that had been knocked off the airwaves by Slobodan Milosevic. B92 kept streaming through the internet from hidden locations. My website was one of the servers that provided those streams, and it remains a real catalyst for my thinking around communication, press freedom and human rights, and the power of media access.

Like many Utopian Internet People of the 1990s, I came to believe that if enough people understood and talked to each other, power would inevitably shift. I am less optimistic about that today.

Portrait of the Net Artist as a Young Man

Most of the work I made prior to 2000 is gone now. My website was hacked at some point, and despite putting together an “International Coloring Contest” asking people to check and see if they had anything in their browser caches, the work was mostly lost. As a result, I have to piece together some of this history through Google and the Internet Archive.

I feel silly saying this, but I want to reiterate that people responded to my work. I was part of the things that were happening on a much smaller world wide web at this time.

I also don’t want to overemphasize it. The people I was talking to did things like publish essays and exhibit work. I never did any of that. I had no idea how to do any of that. I didn’t believe I needed to. I thought the Web was going to replace art institutions! So much so that there was a piece created when I was part of a Belgian artist collective called dBonanzah! — we bought the still-unregistered domain names of major art institutions in Belgium, designed websites for them, and then listed exhibitions of internet artists. A genuine art world disinformation campaign.

But I was active. There’s evidence of me at a conference called Expo Destructo in London in 1999, where folks like the CCRU and the Critical Art Ensemble spoke. I was at Next Five Minutes in Amsterdam, a conference dedicated to media activism and theory. I gave a talk at the Royal University of Ghent with JODI that year. In his State of Net Art 99 Year in Review, Alex Galloway mentioned my work, though I am not sure what I was doing! “Auction Stand for Personal Hate,” where I auctioned off the experience of my hatred to the highest bidder on eBay, came in 2001. That piece was covered by folks like NBC News, and ended up exhibited by the Pace Gallery in 2004 in an event curated by Cabinet Magazine. It’s also in the Rhizome Artbase, but it’s credited to Mark River and Tim Whidden, MTAA, who commissioned the work. (I was also an Artbase intern, working under the wonderful Marisa Olson).

In 1999 Eva and Franco Mattes downloaded the entirety of hell.com, a members-only net art site that tried to create a financial model for digital art long before NFTs. I was a part of it, along with folks like JODI.org and Auriea Harvey. Hell had a massive tent at the Spanish Festival Internacional Benicassim (FIB) in 2000 and 2001 where we projected images behind bands like Fatboy Slim and Clinic.

The point is, I was fairly visible as an artist in my teens and early 20s. But I had no training, no guidance, and no idea what to do with anything that was happening to me. But the net had become a perpetual open studio, a place to experiment and make things and work through things. And I used it to do that.

From ASCII Art to AI Art

I was making art as a way of making sense of the theory that I felt too clumsy to write about in meaningful ways. I was interested in the distance between screens and the world — but I lacked the vocabulary to really discuss those ideas in the communities I was participating in. I was thinking about mediation and reduction, and the border between compression and legibility in communication systems, which shapes the way I look at AI today.

At the heart of AI are the pixels and digital characters that served as the building block for what the Web once was. AI is the last internet art project. It is the most recent formulation of the exchange of information online, because it was built upon that exchange. Moving forward, the Web will reflect the garbled output of itself in ways that radically transform that exchange.

For me, the fusion of glitch art and ASCII art signified the Web’s reduction of the world for the purpose of transferring information while disrupting ideas about how technology should be used. The glitch could be a part of the work, as metaphor for interference, or as an animating force. I would rely on browser hacks and deliberate distortions to transform html into a kind of animation system, to infuse text-based images with movement. It’s still what I do, now, with these AI models. (At one point I was upset that glitches had become aestheticized, stripped of meaning — and wrote a manifesto demanding the end of glitch-focused work as a result. That was uncool of me. Even I kept making it anyway.)

Language was a dismal transmitter. I spent years thinking about images, mediation and reduction online — that is, what did the internet do to the way we see? Today the same questions, and the things I’ve learned, are part of the way I approach AI.

Of course this work owes a huge debt to Vuk Cosic and JODI, and it was hard for me not to see this stuff in terms of “looking like their work.” But I was drawn to these ideas for different reasons, and I believe I found a way to interrogate this visual language toward my own ends.

Here are a few of the pieces I was able to recover and record. Hope you dig them.

Protest Pieces 1-5 (2002)

Here’s one sequence — HEAVY STROBE WARNING! — called “Protest Pieces 1-5.” It’s one of my favorite works from this period. A still from this series was included in the catalog for “Image and Imagination” and the Le Mois de la Photo à Montréal in 2005, curated by Martha Langford.

It’s a series of photos from protests of the International Monetary Fund in 2002, where protesters faced violence from local police who — 14 years later — would be forced to pay restitution. (The protests took place in DC — sorry for the misinfo in the video).

During these protests, I stripped the images to their most “binary” representations — a signal of color or darkness for each pixel. The background flashes in the palette of cop cars: white, red, and blue. The viewer would navigate the image using the browser scroll bars, and the image was outsized, well beyond the limits of browser windows in 2002. All five pieces are shown in the video.

RGB (2002)

I also explored ASCII and animation. I wanted to create the equivalent of an ASCII webstream, and play with the ways we could explore information as it came to us. Images loaded slowly online, so to make video work, I turned to ASCII art. I’d take real video, break it into frames, convert each frame to text characters, and then shrink the display font on the browser window. The result was a something very cyberpunk, a stream of digital text that made a picture.

One piece, “RGB,” allowed the user to arrange three dance performances that were recorded and rendered into ASCII text, shrunk to an absurdly small size, and loaded one at a time in a frame. Each piece automatically called the next page in the series representing the next “frame” of the video, so it appeared like a slow-motion video.

September 11, 2001 (2002)

A piece called “September 11, 2001” used ASCII art as a way of revealing the mediation — or mediatization — of the experience of the September 11 attacks.

I was selling television sets at Circuit City on September 12, 2001. People were coming in to buy TVs and we were having these technical conversations about color resolution and screen sizes while surrounded by 126 televisions endlessly replaying footage of the second plane hitting the towers. Looking closely, we’d discuss the display quality as we avoided acknowledging the images on the screen.

By the end of the day, the images of the collapsing towers had been isolated from what they meant about how I was feeling. It was semantic satiation, like when you say your own name in the mirror long enough that you don’t remember what it means. I know that this was bound to happen to all of us, as we would slowly become desensitized to these images and an escalating series of horrors abroad. But I was stunned, and I wanted to remain stunned — to process it on my own terms — but all I had was TV.

Denisa Kera wrote an essay about “Terrorist Video” that was written for SIGGRAPH in 2002. It describes my piece this way:

The "pixelized criticism" of the media representations uses the familiar images from the TV and alters them in order to deconstruct their iconic function. In the case of Eryk Salvaggio’s online work “September 11th, 2001,” the goal is to show that the slaughtered people are not only "images, tape loops, and abstract symbols" but real people with names and families. Salvaggio uses the letters from their names as "pixels", elements of the famous picture of the airplane hitting the WTC. This picture is no longer only a representation of the destruction of the WTC but more like a poem that connects the victims with these buildings in a very direct and shocking way. It forces us to think behind the media representations and acknowledge that no picture can convey the immense tragedy of these people.”

Here’s a recording of the browser window running the piece. It is slow because each frame is a new web page, loading the weight of hundreds of names.

A Moment

“September 11, 2001” was picked up by Matt Mirapaul at The New York Times, and a piece on it ran on the front page of the Arts Section. A shorter nod in Artforum followed. A Dutch journalist called me “The Harry Potter of the Digital Vanguard.”

But people wanted a lot of different things out of an online memorial to the September 11th attacks. Many people appreciated the work. I don’t know how to assess it in hindsight. But it was the first time I’d experienced mainstream attention like that. I was an untrained artist, a college dropout selling TVs. There were no classes that told me how to make net art, or how to handle critique, or media, or any form of attention. I was already depressed and anxious and resistant to advice.

Online, I was also accused of exploiting the dead, and they had a point. I was told I didn’t acknowledge any of the Afghan civilian deaths that would result from the military response to this tragedy, and they had a point. I was told that ASCII art was an inappropriate choice for a work on this subject matter, and they had a point.

The Artforum comments in response to an online post about the work were especially hard. It was digital art, and a transformation of a news video. People felt — as they often do with digital art — that it didn’t reflect any kind of “skill,” which I disagree with. But I also disagreed that “skill” was what defined “art,” so I didn’t know how to argue it. Mostly I just shut down.

The piece ended up being linked in a lot of platforms where they were using it to push harder for the war in Iraq — the piece came out a year before the invasion, when the Bush admin was trying to convince us Saddam Hussein had nuclear weapons. It was a popular war at the time but I was deeply against it. I resented that this work was becoming patriotic kitsch, a tool for mobilizing war.

The experience was overwhelming for me. I still hadn’t gone to college. I didn’t have any kind of formal art education. I still hadn’t gotten a grip on my anxiety or depression. I was feeling my way through a national trauma and a personal crisis armed with what I’d learned reading Alex Galloway and Geert Lovink on mailing lists. I had no sense of how to respond to the attention or accusations.

On the one hand, the work was being praised, on the other hand, I was being attacked. The misrecognition, for someone who was already deeply insecure about my position in the art and theory world, was too much.

Net Art Dropout

The calloused emotional layer we have all built up through the normalization of online “discourse” was missing for me. I am still bad at this — I had to quit Twitter recently because I am just not set up, emotionally or intellectually, for that degree of misrecognition and the vast sea of bad faith replies.

The intensity of my online experience today is, I think, a holdover from my time on these mailing lists, where I felt bullied, but the bullying would take place behind a veneer of academic critique. Back then, I would bully back, either with or without the veneer. That was one of the worst things I had internalized and perpetuated.

I felt cornered and angry all the time. The only thing I knew to do was react, angrily and strongly, and I hated that about myself. I decided I needed to stop engaging with this world if I was going to become a better person. I had the realization that there was no reason to be doing this to myself. I was maybe 22 years old.

I took all of my work offline. I was deeply, “can’t remember what happened between 2002-2006” levels of depressed. I made a few pieces — mostly about depression, while depressed, which was not helpful.

In 2005, I was invited to give a talk on net art at the University of Maine. Thank god they did. I chatted with Owen Smith and Jon Ippolito and ended up attending as an undergrad in 2006. I earned two degrees: one in new media and one in journalism.

The last work I made with HTML that I actually cared for was a tribute to Nam June Paik. I made it for Jon Ippolito’s web design class in 2006. I was feeling a bit better then, and Paik was an inspiration. When he died, I think I decided that this was the right piece to end on.

This is it, ASCII art and a glitched browser window. When I made it, I don’t think I even had a website to show it on.

And Back Again

After graduating from UMaine I moved to Japan — literally, because I wanted to experience a life where my use of language would be as constrained as it had always felt, but with a concrete explanation. After three years in Japan I went to the London School of Economics for my MSc. in media and communications, where I wrote about technology, mediation, and ideology. I moved to San Francisco in 2013 and committed to a mental health care regimen that finally helped me sort all this junk out and work on being kind instead of demanding kindness. I earned a second masters in applied cybernetics in 2020 at ANU.

I have come to accept that words can never transmit the thing, but that good and careful words could suggest the thing more vividly. Words can make things happen. Policies that protect people from the assumptions language makes about them are far more effective than trying to undermine someone on a mailing list. It was nice to move the ideas I’d been reading and thinking about my whole life from those communities like Nettime and Rhizome and go deeper into the theory and policy side of things — while trusting my words to express ideas and concerns more appropriately.

In 2014, I was included in “Net Art Painters and Poets,” an exhibition of net art related works curated by Vuk Cosic. Full circle back to 1998. It was nice.

And then in 2016 I started making art again. The Internet had become the fuel for AI, and there was something new to make sense of.

August Break

There will be one more post next week, but I am taking August off from writing and thinking about AI in any way. If all goes well, I will have plenty to say in September! I will also send updates on upcoming events as they are lined up.