Infrastructures of Memory

Between archives and datasets.

This week I spoke at the Fantastic Futures conference as part of a panel with Kartini Ludwig and Meagan Loder at the National Sound and Film Archive of Australia. While it was a conversation, I wanted to jot down some thoughts that emerged from it ahead of a video and transcript from the conference. These are not the delivered remarks, but reference them.

Find me on Instagram or Bluesky.

I.

Archives are infrastructures of memory. Memory is never filed away and reopened, like a file on a hard drive. It has to be re-inscribed through action and practice. The infrastructure of memory supports this. It consists of the stories we share, but also feelings, scents, and tastes, or returning to the places where things happened. I’m back in Canberra, and as I walk around Lake Burley Griffin watching magpies and fairy-wrens, I’m taken back to 2020, a year spent here, a year of covid restrictions and cybernetics.

Just as wandering a place after time away can stir memory through our legs, photographs can help us re-inscribe memory from our eyes into our imagination. Still, neither a picture nor a fairy-wren is a memory.

Instead, they are tools for bringing memory to mind, for reviving the story of a place, or a time. When we isolate the photograph, bird, person, or any object from the infrastructure of memory — transport into it a foreign context, or sever its relationship to the story — it loses its power, and memory can become distorted. This is a way to think about archives, and datasets, and the power of infrastructure to shape our access to memory.

The power of shaping and distorting this infrastructure of memory was the topic of a collaboration created with Dr. Avijit Ghosh, called Because of You. This focused on the story of Henrietta Lacks, a Black American woman who, in the 1950s, went to see a doctor. Her cells were taken — and though she felt well at the time, she died shortly thereafter. It turned out that these cells, taken without her knowledge, were also stored without her consent, and became the subject of medical fascination. They kept reproducing. And these cells have contributed to incredible scientific breakthroughs: chemotherapy treatments, for example.

But we noted that these cells were completely abstracted from Lacks’ body, their source, in the medical research. Her family wasn’t informed, or compensated. Instead, the cells were actually mislabeled under a different name, treated as if they came from nobody.

This scientific lens of abstracted bodies, and the information that comes from people, troubles me. I see it today in the ways computers work with the digital traces people leave behind, their photographs and drawings and writing. These, too, are swept up, severed from their source, and used to advance scientific innovation — never considering who is supplying the resource at the heart of it.

In the film, Because of You, we illustrate this by using an image of Henrietta Lacks that is itself abstracted by a commercial generative AI system. The woman in the video has no resemblance to Henrietta Lacks; nor do the AI-generated images of her cells. It is an abstracted portrait — and extractive portrait, a result of aggregated data that may or may not be her, as there are few portraits of her in the world.

Likewise, the film's narration is trained on a 16-second sample of Dr. Ghosh’s voice, which was given to a generative AI system and made to read a script. In the process, the AI “reader” erases the traces of Dr. Ghosh’s accent—a marker of who he is, his identity lost to a sea of North American training data.

II.

These distortions of memory seem particularly relevant to the work of cultural heritage institutions that aim to preserve culture and work with AI to do so.

I think a clarification can be helpful here. The institution is not preserving memory. The archive provides an infrastructure that facilitates the practice of memory. And so it exerts enormous power over the act of remembering, the shape of memory on a large scale.

Contrast all of this with the infrastructure of artificial intelligence. AI is an infrastructure of GPUs, data centers, data annotation and maintenance, model training, water and power. It is an infrastructure focused on the collection and generation of data. This infrastructure may be used to facilitate the practice of memory. But it does not default to this. It has to be steered toward those ends, because the default is to reduce, distort, and excise the particulars in favor of the general.

These are wildly distinct and incompatible architectures. To bring memory to AI, we have to translate it. That means adapting the forms of memory into the forms of artificial intelligence. This is something like traveling with a power adapter: sticking a 110v plug into a 220v socket disrupts the flow of power, distorting and short-circuiting things. So we do our best to make conversions.

One way that happens is through the use of metaphors of transformation. Think of bodies becoming cell lines, photographs becoming datasets. But such transformations do not come without loss. Conversions are rarely clean. We might find that we must make the infrastructure of our memory more malleable to ease the mechanization of our access to it. Then we contort ourselves, the world, and the things that give rise to memory into something less complex — something that fits into the infrastructures of AI. We reduce the artifact to its metadata. We limit ourselves to available fields in the spreadsheet. We restrict the text field to a set of characters.

But we ought to resist imaginations of AI that contort our minds and our shared cultural memory into its structures. If we don’t, we may create ghosts in the machine. Let me explain what that means.

III.

In my work as a Research Fellow with the Flickr Foundation, I explored what lingers after these conversions happen. One way to do this was to look at the source of AI training data for specific prompts. In particular, the phrase “stereoview” is a term that references a specific medium of photography that was popular in the early 1900s. It was the most widely accessible medium of the day. Stereoviews were notable for being two side-by-side images taken at slightly different angles; hold them about a foot from your face, and they’d present the illusion of depth.

AI-generated stereoviews tend to reproduce this side-by-side aspect — here’s a generated one.

What we see here is specific to a time and place, but I never prompted anything aside from Stereoview. In my research, I found this happened over and over again: images of palm trees and certain styles of dresses that had nothing to do with this medium per se.

But when I went into the training data for these image models and explored open repositories for where these images may have been sourced from, I discovered that there was a vast collection of stereoview images from the Library of Congress that referred to stereoview images — and specifically, as a tool for circulating images of the US occupation of the Philippines. The US circulated these images deliberately to tell a story glorifying that project. As expected for a cultural institution, the Library of Congress shared these images online, contextualizing them in an exhibition that showed how this storytelling was crafted and the goals it served.

Nonetheless, when encountered simply as data, these images became strongly associated with the imagery of stereoview images, even to the extent that the very hallmark of the media format — two photos, side by side — would sometimes go away. At the same time, pictures of colonization would remain, as if the word stereoview was more strongly correlated to colonization than to a media format.

IV.

When we convert infrastructures of memory into infrastructures of AI, we abstract meaning, creating conditions of a haunting: the absences of care in that conversion linger in the system.

When an archive becomes data, the infrastructure of memory is compromised. The infrastructure of memory is the system that reactivates memory, keeps it alive in our imaginations, and helps embed memory into living stories and present-day places. Things may shift, but the infrastructure of memory helps us preserve the meaning of things both as they were and as they inform our current lives.

It is worth preserving the distinctions between these infrastructures and treating such translations skeptically and carefully. When memory is severed from meaning, it becomes a hallucination in the parlance of AI. Without the anchor of history and a situatedness in culture, the artifact loses its power to evoke and re-inscribe the memory and stories that give us meaning. Of course, these histories are already highly contested and unstable. The institution that preserves memory also limits the way history can be read. But humans can adapt these infrastructures to be better.

Adapting memory, in all its contestedness, to fit into the infrastructure of AI is a compromise in the wrong direction.

V.

I see lots of talk on LinkedIn from people who want to “co-verb” with AI: “co-create,” “co-author,” “co-operate,” etc. Yet, oddly, nobody seems to dwell on how the AI is “co-opting” our paths to understanding, remembering, or opening up memory. We ought to become highly sensitive to our compromises when working through the AI interface's affordances. A collaboration implies a give and take, a set of mutual compromises. But nobody is asking AI — its industry, interfaces, data collection practices, its infrastructure — to compromise with us.

It is easy to compromise ourselves to what AI allows us to do. What are we being steered toward or away from? How do we collaborate with an unadapting collaborator, and at what cost to the task of preserving access to memory?

Speakers this week mentioned that Australian children are adopting American accents to get their phones to work properly. The imposition of language onto Indigenous people has a violent history. I’m haunted by Peter Lucas-Jones, speaking on US Large Language Models hopelessly biased to English, that “the language that beat our native tongue out of us will be selling it back to our grandchildren.”

AI is not merely a technology; it is a cultural force. The imagination of AI maintains a separate kind of life from what actual AI is and does. We ought to work to separate those things from each other wherever we can—not only because they are profoundly incompatible, and require work to translate, but also because they can lure us into deference to AI: a reliance on its infrastructure that replaces the drive to do things in other, more just ways; knowing that sometimes — often — these are uncomfortable and more challenging.

Much of this comes down not to the technology but to us: the refusal to indulge the myth of its superiority or to contort ourselves to it. It means an insistence on taking time to clarify and work through our decisions rather than surrender them to black boxes of convenience. It means making an effort in the face of a seductively simple option to dissolve decisions into the sudsy foam of automation.

To do so, we must rally an instinctual resistance to the compromises demanded by algorithmic conveniences. We must clarify the purpose of what we do before deferring to what it allows us to do.

Things I Am Up to This Month!

In-Person Lecture and Workshop:

14 Thesis on Gaussian Pop

Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT)

Wednesday, October 23rd 12-3pm (Melbourne)

I’ll discuss my 14 Thesis on Gaussian Pop and the state of AI-generated music in conjunction with the RMIT / ARC Centre of Excellence for Automated Decision-Making and Society (ADM+S) exhibition “This Hideous Replica.” It will combine a lecture on the cultural and technical context of noise in, and the creative misuse of, commercial AI-generated music systems.

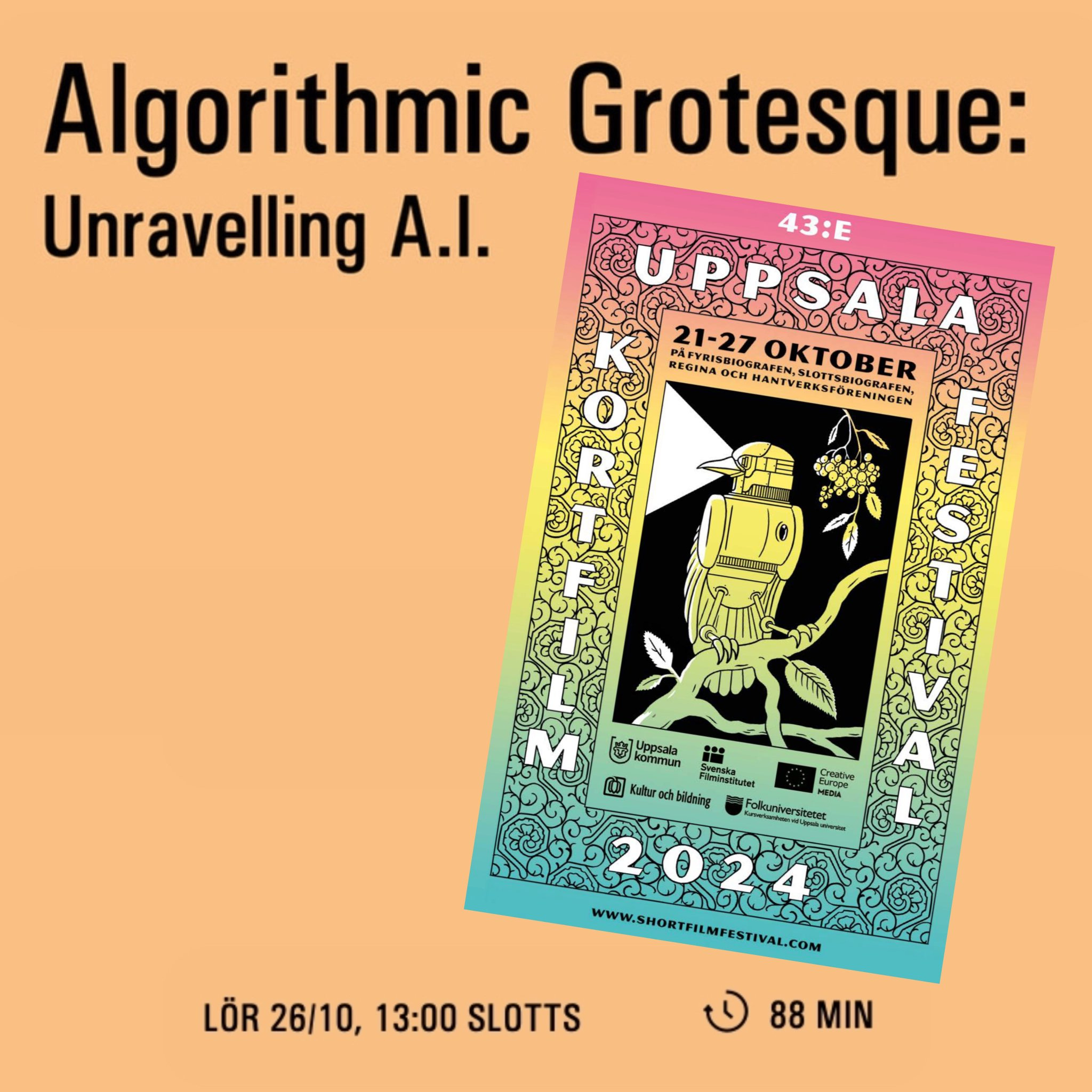

Oct. 26: Uppsala, Sweden Film Festival Screening

ALGORITHMIC GROTESQUE: Unravelling AI, a program for the Uppsala Short Film Festival, focused on “filmmakers with a critical eye toward our algorithmic society.” Great collection curated by Steph Maj Swanson aka Supercomposite. With films by: Eryk Salvaggio, Marion Balac, Ada Ada Ada, Ines Sieulle, Conner O’Malley & Dan Streit, Ryan Worsley & Negativland.

ASC Speaker Series:

AI-Generated Art / Steering Through Noisy Channels

Online Live Stream with Audience Discussion:

Saturday, October 27 12-1:30 EDT

AI-produced images are now amongst the search results for famous artworks and historical events, introducing noise into the communication network of the Internet. What is a cybernetic understanding of generative artificial intelligence systems, such as diffusion models? How might cybernetics introduce a more appropriate set of metaphors than those proposed by Silicon Valley’s vision of “what humans do?”

Eryk Salvaggio and Mark Sullivan — two speakers versed in cybernetics and AI image generation systems — join ASC president Paul Pangaro to contrast the often inflexible “AI” view of the human, limited by pattern finding and constraint, with the cybernetic view of discovering and even inventing a relationship with the world. What is the potential of cybernetics in grappling with this “noise in the channel” of AI generated media?

This is a free online event with the American Society for Cybernetics.

November 1-3: Light Matter Film Festival, Alfred, NY

I’ll be in attendance for the Light Matter Film Festival for the North American screen premiere of Moth Glitch. Light Matter is “the world's first (?) international co-production dedicated to experimental film, video, and media art.” More info at:

https://www.lightmatterfilmfestival.com/

November 1: Watershed Pervasive Media Studio, Bristol, UK

Details TBA! It's an in-person event, but I’ll be remote — and speaking on the role of noise in generative AI systems. Noise is required to make these systems work, but too much noise can make them unsteady. I’ll discuss how I work with the technical and cultural noise of AI to critique assumptions about "humanity" that have informed the way they operate. A nice event for discussion with an emphasis on conversation and questions.

Through Nov. 24: Exhibition: Poetics of Prompting, Eindhoven!

Poetics of Prompting brings together 21 artists and designers curated by The Hmm collective to explore the languages of the prompt from different perspectives and experiment in multiple ways with AI.

The exhibition features work by Morehshin Allahyari, Shumon Basar & Y7, Ren Loren Britton, Sarah Ciston, Mariana Fernández Mora, Radical Data, Yacht, Kira Xonorika, Kyle McDonald & Lauren McCarthy, Metahaven, Simone C Niquille, Sebastian Pardo & Riel Roch-Decter, Katarina Petrovic, Eryk Salvaggio, Sebastian Schmieg, Sasha Stiles, Paul Trillo, Richard Vijgen, Alan Warburton, and The Hmm & AIxDesign.

Through 2025: Exhibition

UMWELT, FMAV - Palazzo Santa Margherita

Curated by Marco Mancuso, the group exhibition UMWELT highlights how art and the artefacts of technoscience bring us closer to a deeper understanding of non-human expressions of intelligence, so that we can relate to them, make them part of a new collective environment and spread a renewed ecological ethic. In other words, it underlines how the anti-disciplinary relationship with the fields of design and philosophy sparks new kinds of relationship between human being and context, natural and artificial.

The artists who worked alongside the curator for their works to inhabit the Palazzo Santa Margherita exhibition spaces are: Forensic Architecture (The Nebelivka Hypothesis), Semiconductor (Through the AEgIS), James Bridle (Solar Panels (Radiolaria Series)), CROSSLUCID (The Way of Flowers), Anna Ridler (The Synthetic Iris Dataset), Entangled Others (Decohering Delineation), Robertina Šebjanič/Sofia Crespo/Feileacan McCormick (AquA(l)formings-Interweaving the Subaqueous) and Eryk Salvaggio (The Salt and the Women).

Cybernetic Forests is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.