Interdisciplinarity means Intersectionality

Universities organized books and rebuilt the Tower of Babel.

The way we study knowledge is all about keeping knowledge steady once discovered. You wouldn’t sail south to reach the North Pole, and you wouldn’t study ship building to learn how a light bulb works. We know, generally, how to get from zero knowledge about something to some knowledge about it. That simple concept influences how we arrange libraries, academic departments, and grant funding schemes.

When European universities began to secularize, they needed ways to organize that incoming flow of information. So they categorized it into disciplines, mostly defined in terms of which kind of information moved you toward a certain circle of knowledge in a particular circle of ideas that complemented and reinforced one another.

This lead to an information management problem. These specializations soon went beyond their boundaries as people began asking new questions, fragmenting the disciplines even further. A student at the University of Paris had four possible subjects to study in 1231AD; today it has been broken into 13 individual schools. As knowledge becomes more specialized and its language more individualized, there is simply more to know before you can answer — or even pose — a novel question.

This has isolated fields of human knowledge — the kids in the art schools do not always get to talk to the kids in engineering schools — and so not only do we now have “types of knowledge” (and “types of knowledge-havers,”) but these fields have become so specialized that they lack common frames of reference and vocabularies to communicate with others — sometimes even within the fields they study.

And yet, those conversations hold the greatest potential for new ideas to emerge when they do. Knowledge takes root slowly when isolated, but blooms in pollination.

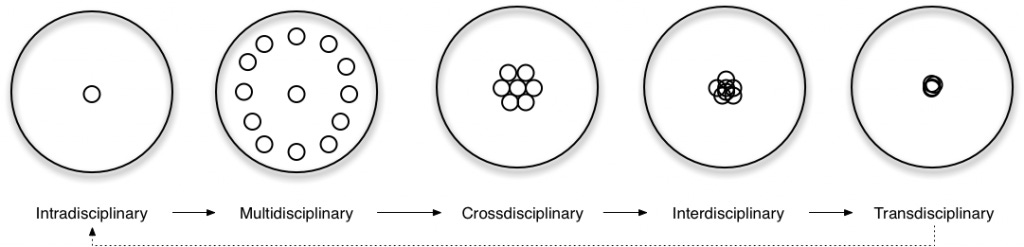

Today, in my particular world of rando-disciplinarity, responses to the idea of disciplines becoming disciplines themselves: hyphenated disciplinarities. In particular, we have trans-disciplinary, inter-disciplinary, cross-disciplinary, multi-disciplinary, even anti-disciplinary and post-disciplinary positions. Each marks a particular strategy of “connecting the dots” between ideas and worlds.

Each of the models in the diagram above suggests that new combinations of expertise can result in new collaborations and insights. Each dot also represents a particular way of imagining knowledge, and placing these imaginations into proximity is the actual “trick.” These imaginations go beyond disciplines, they are positions. The way we imagine the world is shaped by what we know of it: if we are able to imagine more, rather than concretize one vision, we can expand the ways we see, and so expand the things we are able to know.

Interdisciplinary efforts are often defined by already narrow disciplines rather than personal experiences. An intersectional disciplinarity might go beyond “common” points of reference and instead seek out divergence points between a range of experiences and positions, all aimed at re-imagining how that field came to organize its knowledge. It should aim to destabilize from within.

In other words: it’s not just what experts know, it’s what experts imagine. And once we get into the imagination, blending expertise is just one part of seeing a truly balanced world. The other trick is imagining it.

In “Strong Objectivity,” Harding notes that the imagined world of an expert, when communicating with other experts, can be abstracted into theoretical excersizes and possibilities, rather than the impact of that knowledge on real lives.

Harding writes that, in ignoring the social, emotional, and human reality of their work, the focus on academic expertise can “promote moral detachment in scientists which, reinforced by specialization and bureaucratization, allows them to work on all sorts of dangerous and harmful projects with indifference to the human consequences” (Harding 1995, 334).

“Cybernetics” has a bad rap in some circles, as it seems to be connected with a particularly narrow set of ideas about the organization and categorization of knowledge, externalizing one way of thinking (predominantly white, European, male) into a set of machines. It has been accused of seeking to become a “universal science,” seeking to re-unify fields of psychology, robotics, computers, and anthropology (all present at its initial conferences).

The result could certainly be interpreted as a universalizing ideology, a way of asking all others to conform to one set of rules and languages. I don’t doubt that computers, as an ideology, are doing precisely that. But if we’ve built this problem, we can dismantle the problem.

We might reimagine cybernetics — the “science of communication and control in animals and machines,” — as a call to a deeper engagement with all of these things. There is no reason why we shouldn’t imagine it in broader, contemporary terms. It could be looked at as an attempt to listen, rather than control. It’s all about how we build it.

What could cybernetics be if instead of exclusively combining domain expertise, it also embraced a diversity of lived experience? Why limit the exchange of knowledge to “disciplines,” when people without academic expertise also know?

This week I’m thinking about practice: if all that I just described is known to us, justifiable, and makes sense, then what? I think about this as a space where art might move, with its drive toward new imaginaries and possibilities through radically expanding our ways of seeing.

Things I’m Doing This Week

The video collage and sound piece I put together for Ellen Broad’s Telstra Keynote at Melbourne Design Week is online to stream at the National Gallery of Victoria website. Ellen wrote the text, and together we worked out how to deliver a keynote in the Zoom era. The result is an audio/visual musical experiment, connecting collage and AI-generated imagery as a kind of VJ set with a musical score that embraces cybernetic principles of feedback.

It’s focused on reimagining the future of Artificial Intelligence from the “antipodes” — the opposite of the center, which is where one might place Australia in the scheme of AI. But it also looks to other peripheries for inspiration in imagining technologies, from literature to the natural world. It was an honor to work with Ellen to produce a backdrop of sound and images for this beautifully written piece. I hope you enjoy it!

The ANU School of Cybernetics has also put up a short interview with Ellen and I about the process behind it, which you can find here.

Things I’m Reading This Week

From Rationality to Relationality: Ubuntu as an Ethical and Human Rights Framework for Artificial Intelligence Governance

Sabelo Mhlambi

How would we move artificial intelligence away from one definition of expertise — let’s call it the rational imagination — toward a relational one? In this paper Mhlambi draws on the Sub-Saharan African philosophy, ubuntu, to reconcile “the ethical limitations of rationality as personhood by linking one’s personhood to the personhood of others” and “shows that the harms caused by artificial intelligence, with a particular focus on automated decision making systems (ADMS), are in essence violations of ubuntu’s relational personhood and relational model of the universe.”

“The traditional view of rationality as the essence of personhood, designating how humans, and now machines, should model and approach the world, has always been marked by contradictions, exclusions, and inequality. It has shaped Western economic structures, … political structures, … and discriminatory social hierarchies which in turn shape the data, creation, and function of artificial intelligence.”

###

To Live In Their Utopia: Why Algorithmic Systems Create Absurd OutcomesAli Alkhatib

Alkhatib presents his paper, condensed into a five minute YouTube video. I’m a fan of that approach. Here’s the thesis:

Machine learning systems construct computational models of the world and then impose them on us, not just navigating the world with a shoddy map, but actively transforming the world with it. … And all of their behaviors in turn shape ours, so that we appear more legibly to this incredibly limited system. These systems become more actively dangerous when they go from "making sense of the world" to "making the world make sense.”

###

HCI and deep time: toward deep time design thinking

Jörgen Rahm-Skågeby & Lina Rahm

A paper reimagining the length of design cycles for human-computer interactions to extend much further beyond the human lifetime. (Sadly paywalled).

To see objects not just through the lens of human agency but through the lives of nonhuman beings that both shape and are shaped by relationships and processes embodied in material forms is to invite stories – in fossilized bones, decaying tissue and living flesh.

The Kicker

Growing up in Mexico City in the 1980’s, Eugenio Tisselli loved video games but didn’t have a computer. So, he learned BASIC from books, imagined games in his head, and wrote the code on paper. In 2008, he discovered those notebooks, and reproduced the games, making them free to play. Check out the notebooks, the games, and the code here.

Thanks for reading! As always, if you dig it, please share it! I rely on word of mouth to grow. And if you were recommended this post, subscribe to get a new one every Sunday. It’s free, but if you want to kick in $5 a month, you will have my heart.