Moth Glitch (2024)

From Stan Brakhage to Stanning Breakage

It’s summer, and I made a new thing. It’s shown above. I will ramble a bit about it below, as I try to think through a weird set of questions. I’ll talk about Stan Brakhage and machine learning and moths and computer errors.

First, a caveat about geniuses, and art named for names. There’s not really anything wrong with these people we call geniuses, unless they assign it to themselves. But there is something inessential about the practice of naming a way of understanding a medium after a person. That’s a kind of AI prompt logic. Prompting points a model toward Kingdoms in the Art World the way a URL points to a website. Territory is, unfortunately, how people have to interact with one another to survive on planet Art World. You can’t give ideas away for free, because not only will you be unable to eat but eventually everybody will eat you.

This isn’t to justify plagiarism or theft, which is the cynical exploitation of a flawed system. What if, instead of geniuses, we just set a table where ideas can flow generously between equally invested artists who gravitate toward the same ways of doing things?

This week Stan Brakhage happens to be at the buffet table, but let’s not mistake him for the person who discovered sweet and sour chicken. He doesn’t get a crown for gluing moths to celluloid, but it seems kind of cool to read up on what he might have been thinking and why it resonates.

Below is the film, below that is the film.

Stan Brakhage’s 1963 book, “Metaphors on Vision,” is useful to turn to, as computer people, because computer people also rely on metaphors on vision. He has this:

Imagine an eye unruled by man-made laws of perspective, an eye unprejudiced by compositional logic, an eye which does not respond to the name of everything but which must know each object encountered in life through an adventure of perception. How many colors are there in a field of grass to the crawling baby, unaware of "green"? ... Imagine a world alive with incomprehensible objects and shimmering with an endless variety of movement and innumerable gradations of color. Imagine a world before the "beginning was the word."

I want to imagine that kind of vision, though it takes a minute. Is it appropriate to compare this to Generative AI? Machine Vision, maybe. But Gen AI is not actually responding to a world before “the beginning was the word,” because the “word” is an essential variable infused into the calculus of the training process. Gen AI is arguably the opposite of “an eye unruled.” AI models, when used as intended, don’t get us away from the bias of human vision, it constrains us to that bias: the bias collected in training data, a bias that emerges images in the categories of their descriptions, reconstructing links between words and what they represent.

Artists might try to break away from that constraint. Brakhage is an interesting example: a film that looked at all the mechanisms of cinema used by an artist who said “what if we used the same tools differently?” In using AI, we are expected to rely on the logic of images and associations in the training data. A computer is unaware of green, but the word green, the shred of text that results when we place a g beside an r beside two e’s and an n, becomes a reference to a limited, previously selected range of noise-infused photographs of grass patches. It’s an image of the image of the world, an illusion representing an illusion.

I spend a lot of time thinking about hijacking that illusion, and making something apart from it, just to see what I learn by occupying that space.

You know what else hijacks computational constraint with varying degrees of success? Moths.

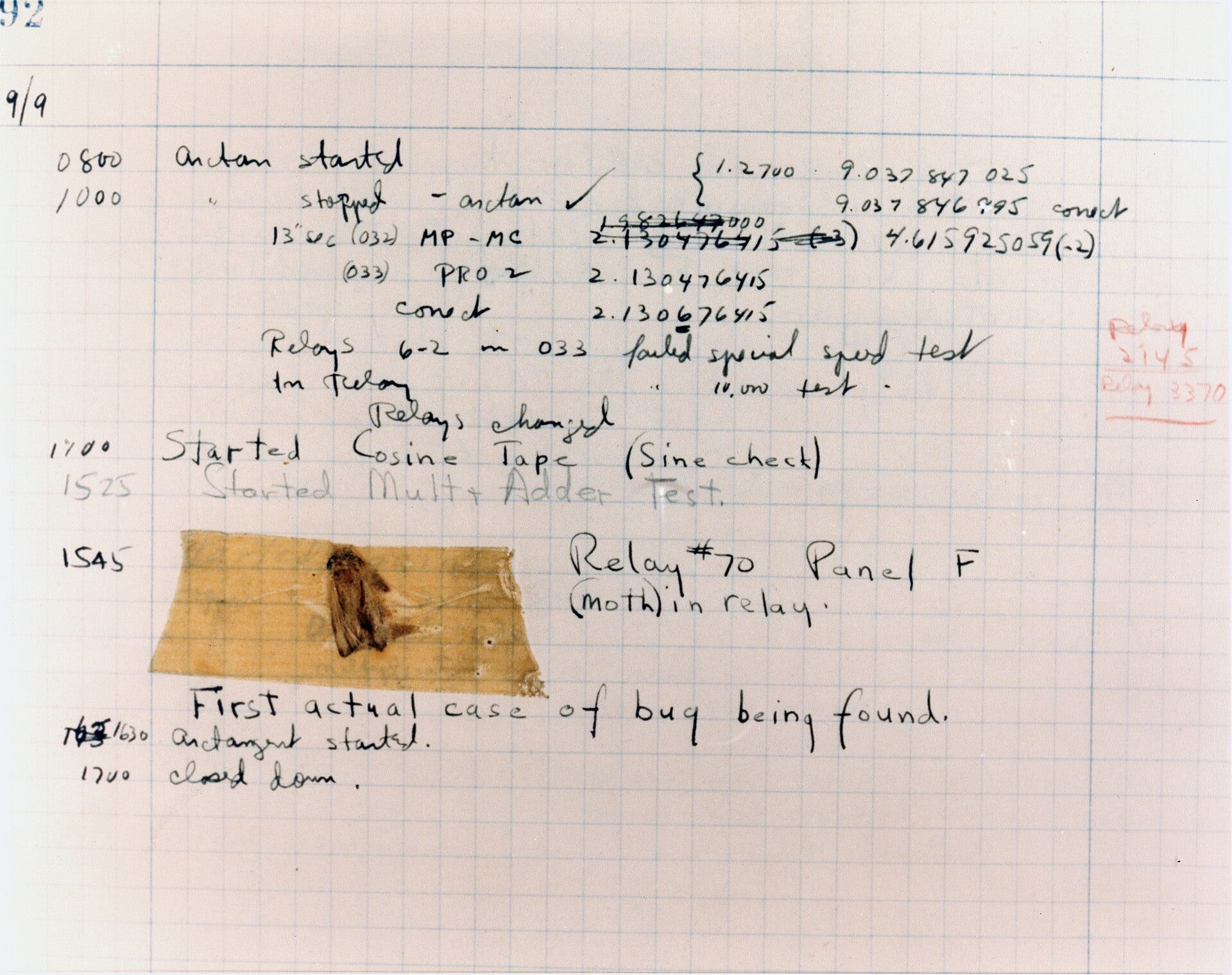

Moth in Relay

The first glitch inside a computer system was a moth. It found its way into a MARK II in 1947. The team using the computer (which included Grace Hopper) taped it into the notes. This idea of the bug to describe a glitch was around since Edison’s telephone wires, but the MARK II moth cemented (or taped) its persistence into the computer age.

When I think of Mothlight’s moths, stuck between the lamp of the projector and the light of the screen, I remember the moth stuck in Relay #70 Panel F, a glitch taped to a notebook.

Moth Glitch is a new experiment with AI generated things: moths and music and noise and glitches. I call it an homage to Stan Brakhage, but maybe it’s more appropriate to call it an homage to moths.

Noise, as I have discussed often, is at the heart of generative AI. It is what creates the illusion of creativity in these images and videos. Paradoxically, AI systems can’t produce noise, because noise is too complex. These are systems that require compression, and compression introduces bugs.

I’m interested in pushing on the boundaries between compression and legibility. I see that in Brakhage’s Mothlight, with real wings serving as a replacement for the imprint of light in the shape of their wings, into film. The moth is a glitch, a computer bug, a thing that disrupts the tidy compression of the world into a stream of bits, or interrupts the stream of images that presents a hazy, hallucinatory effect of cinema.

Too much complexity overwhelms any system’s capacity to compress it. For an AI system, this leads to glitches too. Diffusion models are designed to remove noise to find images in an image of noise. If you ask it to create noise, you bypass internal systems that seek to recognize images. You steer the system away from representation.

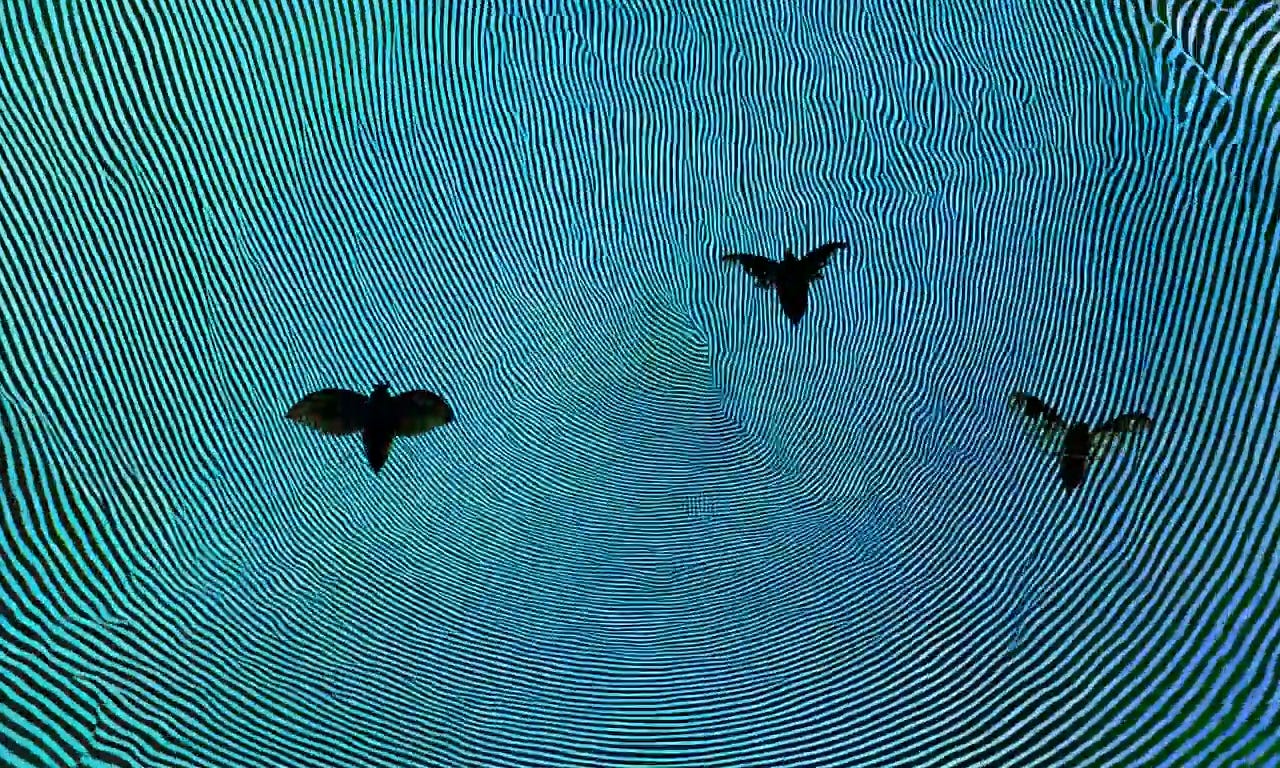

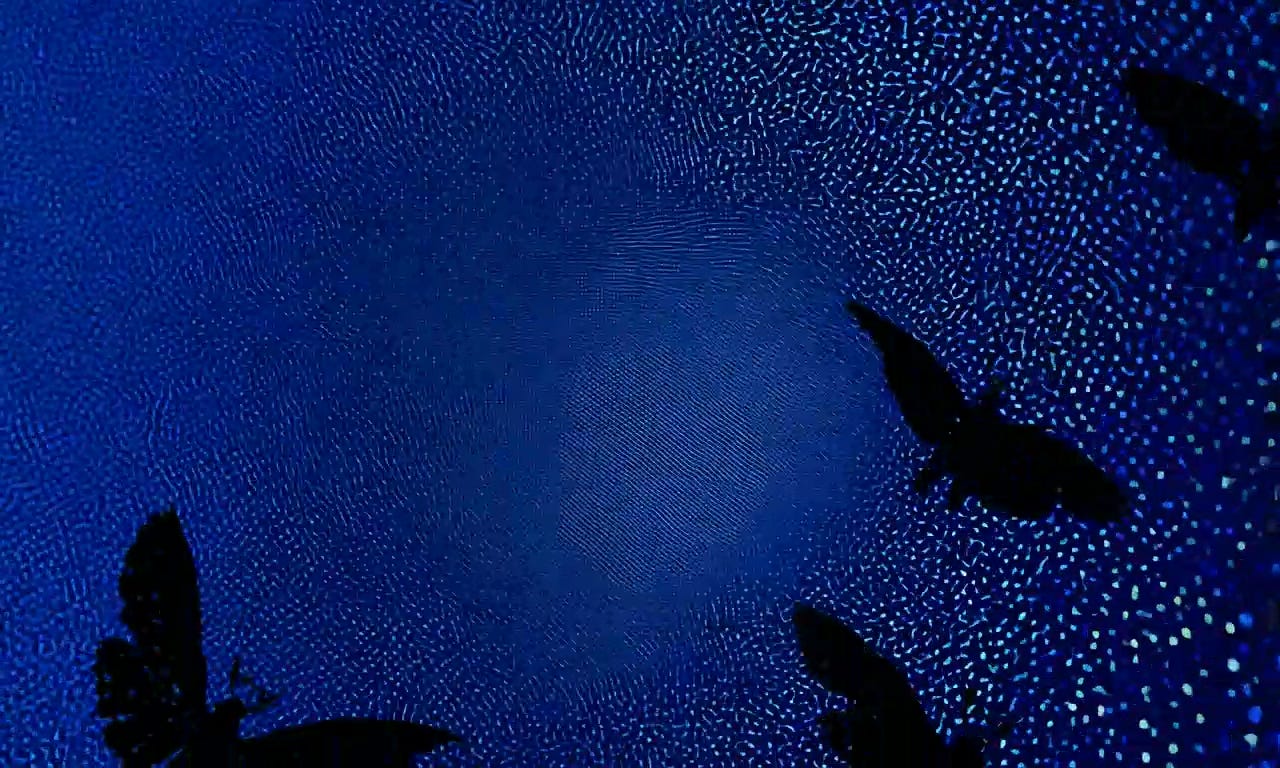

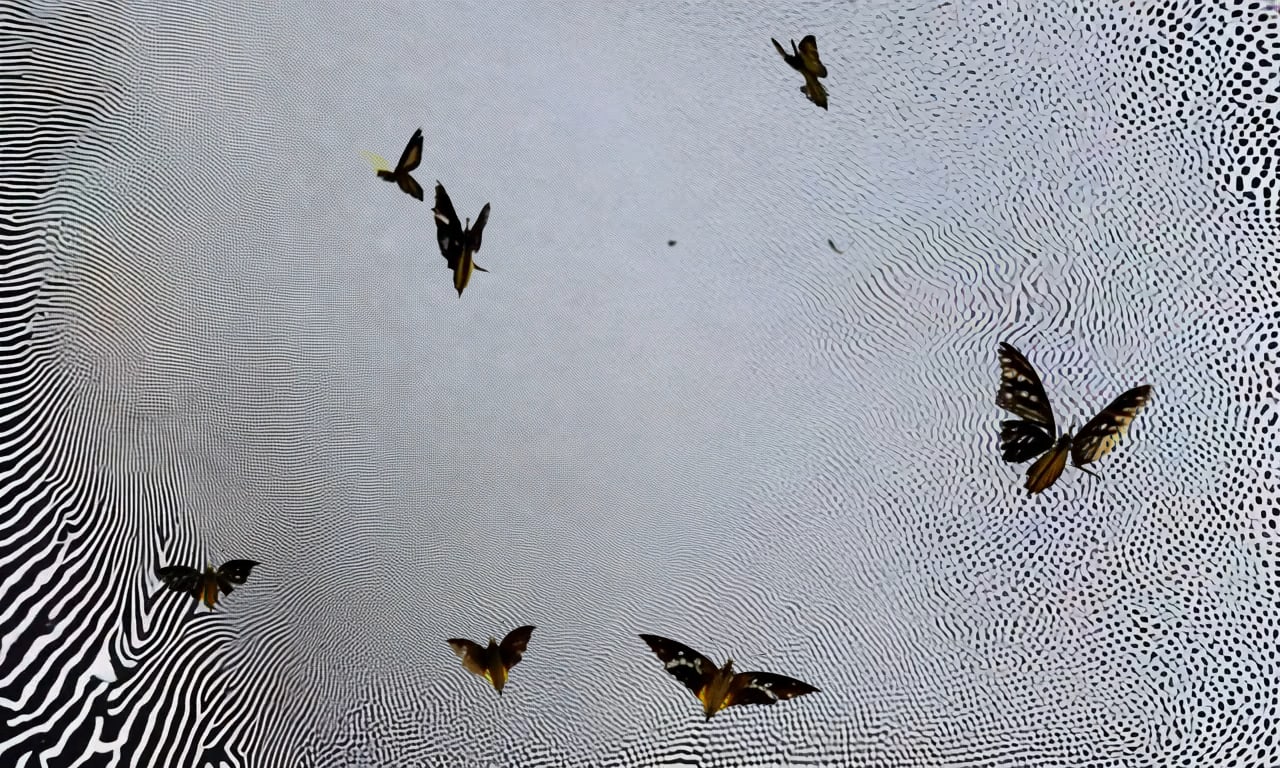

Yes, when I prompt noise I get an image of noise. But the resulting noise is not what’s in the training data. It’s noise produced by an actual, technical failure in the model: a prompt for noise is like a moth flying around inside a digital infrastructure, rearranging patterns of light into colorful, swirling smears that push the boundaries of compression, creating moire patterns and image breakdowns and new things for us to see. Things without references in the data, though perhaps they contain references for the rest of us.

That’s what we see behind the moths of Moth Glitch — the glitch part of the title — as swirling bursts of shifting texture and color. These are accidents of the system.

In the foreground is the moths. There is something whimsical about watching what passes as moth flight within an AI video generator. Yes, it’s bad at it, but I find it a charming insight into the system’s limits, at odds with the imagination of AI as a superhuman physics engine modeling our world.

AI will get better. I don’t want to point at these moths and laugh at them. I like them. I prefer them to realistic video renderings of moths. Something will be lost if these models become perfect.

There are real moths (the things taped to film strips), but also hypothetical moths (images a machine predicts based on past images), and there are real errors (images that result from prompts that break the system) and hypothetical errors (images that are what the model predicts based on images in the training data).

Stan’s moths were real moths. His Mothlight film was described as being “created by painstakingly collaging bits and pieces of organic matter—moth wings, most notably, as well as flowers, seeds, leaves, and blades of grass—and sandwiching them between two layers of clear 16-mm Mylar editing tape.”

Both of us are working with dead moths. I’m working with them as traces of real months, recalculated from the dataset into a renewed simulation of animation. He was working with the moths plucked from his window. The film was shown with pieces of wings and petals grinding through a projector; not the digitized YouTube stream we just saw. The moth was in the room with us.

When working through AI, I find myself thinking about Mothlight quite often, with a deliberately absurd question: how do you get at the materiality of AI through its output? Here, I’m at risk of imagining materiality too literally. That would mean data centers, fiber optics. Materiality is not the right question at all! But I want to see what the wrong question gets me.

There has always been a state of constant slippage between what is represented and what represents it. The digital requires an immersive imagination to operate: we need to believe that we are submersed, that images represent what is really there, even if it is half-formed, like a daydream of a moth. Whatever social media eroded about images, AI has pushed into the sea. Instead, what is really there can only be indirectly referenced, seen as traces in the outcomes. The trace left in the image is a residue of its collective references. Lots of moths make the moth.

Stan described making the film as an effort at no-camera cinema, a way of assembling images onto film and projecting them without requiring them to be processed through the apparatus of the camera. Instead of being filmed, they are pasted directly onto film strips, which are projected directly on a screen. Just light and insect wings.

“I tenderly picked them out and start pasting them onto a strip of film, to try to ... give them life again, to animate them again, to try to put them into some sort of life through the motion picture machine,” he says in a director’s commentary on the Criterion DVD.

Moth Glitch is the opposite of this, maybe: the moths are illusions. The glitches — those swirling backgrounds — are the real moths, but also the light directly out of the machine. It’s not as heavy, not as experimental, not as intellectual as Stan’s work. I don’t mind. I just wanted to figure something out — rather than “what about all these dead moths?”, I wanted to know what I should do with all these glitch experiments, this thing that says something, I think, but what? And how does it say it?

Old Man Yells At Cloud (Computing)

Does everything made with AI have to be at war with AI? I think if we say yes, then we end up defined by the terms of the technology just as much as if we used it uncritically.

I often assign myself a role in a sub-Kingdom of the art world called AI art, but that’s at odds, in many ways, with how the field of AI and art are coming together. I am often critical of technology, and criticality is an essential piece of making technology more just. I happen to use art as a way to think and feel through it.

People are trying to make sense of technology all the time, and not everybody is coming at it critically. Artists can have a role in shaping a more critical engagement of technology, though of course it is not their job. AI art has put this into a new perspective, as artists who engage with the technology creatively are often referred to as navigating the technology, or offering insights into what it is and does.

Personally I think there is too much imagination about AI. I always aim to make work about technology as a kind of meditative practice, that is, to help strip illusions and imagination away from it. To see the technology for what it really is and what it does in its interaction with our world, its role in co-constructing a way of seeing that sorts by who has and lacks the power to challenge it.

The glitch is a way to do this — to steer away from the imagination of AI as a creative partner, and reveal the simplicity of a system running astray. Here we lay it out: some data about moths, “taped” to a screen by an AI image generator asked for the shape of moths, “pinned” against a backdrop of generated light patterns, an image too complex for the system to correctly render.

Stan wrote about this, too, in 1963. Who knew? I didn’t. For Stan it wasn’t Microsoft, it was IBM.

“The increased programming potential of the IBM and other electronic machines now capable of inventing imagery from scratch. Considering then the camera eye as almost obsolete, it can at last be viewed objectively and, perhaps, view-pointed with subjective depth as never before. Its life is truly all before it. The future fabricating machine in performance will invent images as patterned after cliche vision as those of the camera, and its results will suffer a similar claim to ‘realism,’ IBM being no more God nor even a “Thinking machine” than the camera eye all-seeing, or capable of creative selectivity, both essentially restricted to “yes-no,” “stop-go”, “on-off,” and instrumentally dedicated to communication of the simplest sort. Yet increased human intervention and control renders and process more capable of balance between subjective and objective expression, and between those two concepts, somewhere, soul.”

It is fun, then, in a buffet-style-lunch kind of way, to think about human intervention and control, to think about an AI image that has at least one illusion removed, and what it might be. Moth Glitch is a not-so-serious answer, or maybe it is. Frankly it was a fun film to make, a way for me to navigate serendipity and process and think about what materiality means for data in a vector space and insist on being wrong about it. In the end I liked the way the moths moved with the music, which added some context: “A point in memory / beyond precise recollection / a residue of the experience / lingers within outlines / Shaped by language, the words we give / to this experience / shape what returns to us.”

August Break

I am taking August off from writing. See you in September!

UMWELT, FMAV Modena Italy

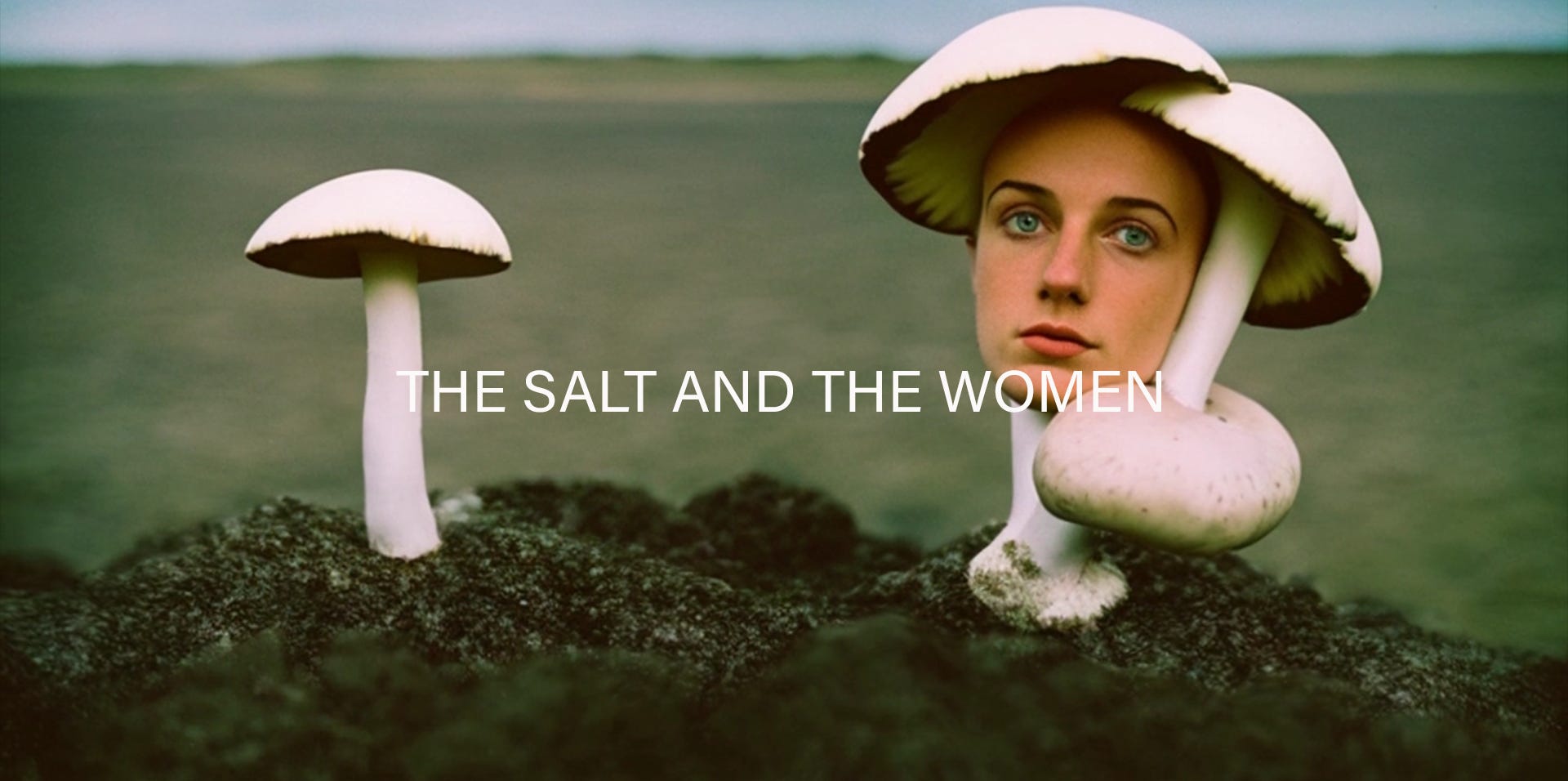

I am excited to have a short video piece in the upcoming UMWELT exhibition at FMAV Palazzo Santa Margherita in Modena, curated by Marco Mancuso. My 2023 film, The Salt and the Women, will be presented alongside works by Forensic Architecture, Semiconductor, James Bridle, CROSSLUCID, Anna Ridler, Entangled Others, and Robertina Šebjanič / Sofia Crespo / Feileacan McCormick. The catalog includes texts from Marco Mancuso, with Daphne Dragona, K Allado-McDowell, and Laura Tripaldi.

From the exhibition text, UMWELT "underlines how the anti-disciplinary relationship with the fields of design and philosophy sparks new kinds of relationship between human being and context, natural and artificial.

Bunjil Place, Melbourne Australia, August 10

I will be speaking remotely as part of the ART BITES: AI Technology in Art - Creative Tool or Threat? panel on August 10 at 12:30pm, alongside artists Betty Sargeant, Matt Gingold, the legendary Mez Breeze (live from Canberra) and moderated by Pierre Proske. You can also catch my film, SWIM, which will stream overnight on the screen outside Bunjil Place for all of August as part of the art after dark programme.