My Father's Data

My father died on June 30 while rescuing a bird trapped inside his garage. While closing a window behind it, he fell from a ladder, lost consciousness, and died. It was the week of his birthday, and he had gone out with three groups of friends over the week. He was on his way in to have cake with some of them when it happened. He died, having spent time with people who loved him, while trying to reduce a small bit of suffering from the world: may we all be so lucky.

For much of my childhood, my memory of my father was of him coming home in the darkness after work, lying on the plush brown couch in our living room with his arm over his eyes. Yet that man had hints of the person who would emerge as we grew older. His sense of humor came through then in his creative pranks and playful misdirection. I remember him convincing me that he could control traffic lights by tapping the roof of his car: he only mentioned this fact just as he'd see the switch to the yellow light on the other side. But to a kid, it was magic.

But Dad on the couch needs a mention here too. Not to condemn him for it, but to say that I have come to understand it. As I grew older and struggled with depression on my own, I also saw my father emerge from it, both in his own life and in his relationship with me.

I learned some things about my father only after he died. He never spoke about his time in the war. He was drafted in 1969 and served until early 1971. His job was to drive a truck and search for land mines. At one point he was called into a disciplinary meeting for a failure to wear his hat properly — and the soldier sent in his stead that day was injured. My father took this story and believed that it was his fault, and the guilt for this ate at him for the rest of his life.

My father had recorded a set of experiences down when he returned, and his file, which I'd never seen until now, described some of them, alongside dates. His letters home – which I'd never read until now – said nothing of these things. His letter home, after witnessing a particularly gruesome accident he never discussed with anyone, was two pages pointedly reassuring his mother not to worry about him.

My father was barely 20 years old then, and already the world had told him that lives could end if he made a single mistake, and at the same time it didn't care if his life ended because of its mistakes. The awful realization of the callousness of power seemed to convince him to keep it secret, as if talking about the void at the center of the world was a contagion.

The awful realization of the callousness of power seemed to convince him to keep it secret, as if talking about the void at the center of the world was a contagion.

My father on the couch was 35 years old. I remember his arm over his eyes and I know it, because I do it too, when I wanted to be unreachable, when I needed to withdraw into myself. I am telling you this not because he wasn't a great dad, but because he was. Because I watched, over the last 20 years, that arm come away from his eyes and start looking at mine, my mother's, my wife's.

My dog. I told my wife, before our first trip with the dog to see him, that my father would love our dog because our dog would look at him. She looks you in the eye. I was right. That was all it took for my dad to love her: "She really looks at you."

The stories in our heads, the memories that pull down hope, they can attach themselves to our limbs, hold our feet to slow our gait. But my father – a postal employee for the entirety of his life after the war – walked every day. We calculated, in the early days of this century, that he had already circumvented the entirety of the globe more than once while delivering the mail.

My father carried baggage, ghosts that dragged him down. But he walked. And he did something remarkable: he outpaced the memories. Not forgetting them, but he got somewhere. His hands moved away from his eyes. His eyes started to see me, and the world, and his garden, and his life.

People say my father was a great guy, and he was. He was great because he saw you, and he knew when you saw him. It is not easy to transform ourselves from averting a gaze to embracing it. I learned from my dad that we can eventually come to terms with the pain that shackles us. The weight of our burdens, our traumas, and our pain may never leave us completely, but that we can find buoyancy too: with distance, they can become an anchor rather than drowning us.

My father died trying to rescue a bird trapped in a garage. The weight was there. In that desire to reduce that small bit of suffering, I could see the evidence: he had transformed the burden of memory into a desire for kindness and an incentive to action. He could see how heavy the world could be. But as a bird flew through a window, and my father fell to the ground, we lost him. But I know he was lighter than he had ever been.

Death Denial

In the week my father died I was meant to be on a plane from one AI-focused residency in Rome to a week of events about AI in Melbourne. It is ingrained in me, now, to think through the metaphors of this technology, even now. It may seem banal, influencer-esque, like some monstrous LinkedIn post: "10 Things I Learned about AI from my Father's Sudden Death."

But while I've always suspected that AI is about a denial of death, in the aftermath of the traumatic and unexpected arrival of the Real, I feel this even more deeply. AI promises an illusion of steady continuity in a world full of unexpected redirection. Nothing shatters that illusion of perpetuity like the sudden death of someone you love.

The denial of death is not completely insensible. I am raw these days, increasingly worried about things that would have been unnoticed around me: kids messing around near a pool, my wife going for a drive.

Death is only as far away as a six-foot ladder. We naturally want to put that out of our minds, but we can also do so irrationally. This rawness is bringing a sensitivity, too, an expanded empathy. I am worried about strangers and birds, I am more anxious but more empathetic. I am noticing other's pain more often. Somehow this will need to return to an equilibrium. We do not need to presume we will not die, but to live a real life, we need to pretend it will not happen today.

We do not need to presume we will not die, but to live a real life, we need to pretend it will not happen today.

Culturally, there seems to be a slowly eroding belief in our culture about the separation of the simulated and the real world. More people assert that the core distinction between the experienced world and its reproduction is simply a matter of producing enough data or density of detail.

At the same time, we are in a battle over the limits empathy has on this optimization. The rejection of empathy is held up as a new ideal among the tech and political elite. We invest in "superintelligence" as a pathway to the complete transformation of the body into divinity, which is conjoined with what has become, ultimately, a near-gleeful rejection of humanity.

I understand this wishful thinking: it's fear. This specific imagination of AI is a way of protecting ourselves from the harsh objective reality of natural limits by detaching from it. Spending more and more time in worlds where we can save the game in a specific state and endlessly tweak the outcomes, re-enact and reshape the moments and time with people we fear we are destined, inevitably, to lose.

Nor is AI the first or only technology that aims to extend this dream. Media is a synthetic Bardo state, poised between a world that disappears and the perpetual now in which we return to them. That is the history of photography and the moving image. But ceding our world to the myth of television or images never seemed helpful, either. AI is as much a spectacle as any other medium, but unlike those other mediums, it has novel specificities and a set of myths that we are not yet prepared to resist.

AI is as much a spectacle as any other medium, but unlike those other mediums, it has novel specificities and a set of myths that we are not yet prepared to resist.

The embrace of Machine Learning's mythology is rooted in the denial of death and a resistance to endings, in that it examines the past to tell us the future: this is nothing new. But when we shift such pattern finding from the territory of generating insight into the terrain of automated action – refusals and allowances based on the past, without any grace or intervention – it becomes a refusal to acknowledge the potential for transformations within people and systems. It binds.

Data only tells us what we've captured, not what has evaded capture, and the tricky thing about the world is that so much of it is hidden behind the words.

The Text

People use AI for grieving loved ones, but a statistically likely reproduction of my father's words would offer me absolutely no comfort. My father did not express himself through words. He expressed his love through what was not said: by keeping information about the pain of the world close to him.

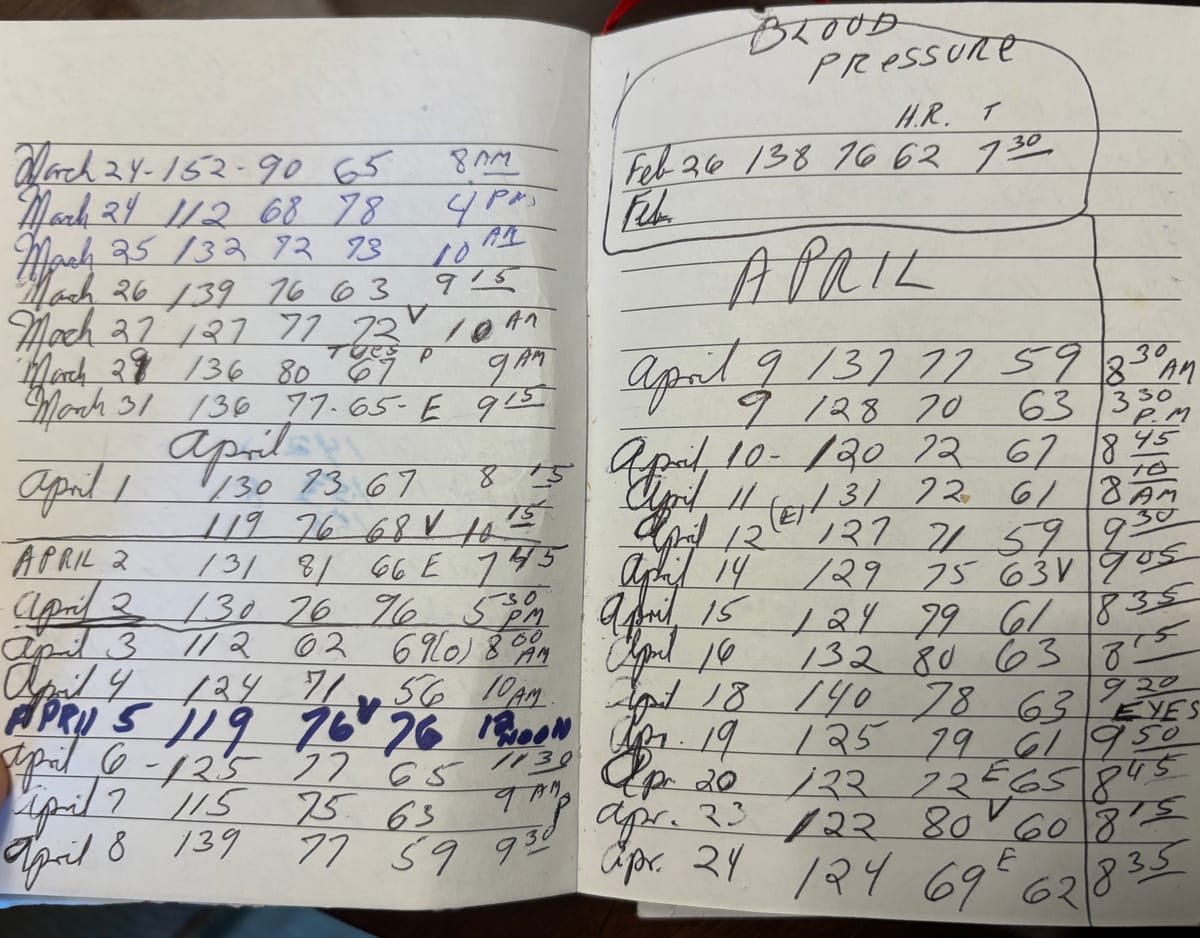

He expressed love, instead, through time: sustained and steady presence and attention. It's not there in the numbers he recorded about his life: he had a red notebook full of twice-daily blood pressure readings, bread recipes, bill payments. This data is meaningful, in that it is all the residue of my father's life – surfaces marked and changed by his existence – but no assemblage of it would ever recreate him. Nor would any collection of the texts he'd sent — a word, a thumbs up. All of that is the residue of time.

Looking at it shows the limits of such debris in recreating the presence of a person or the state of a world. At best, the data we leave behind gestures toward a person, markers pointing at what paths they had chosen. But the person is not only the paths they take, the person is the navigator of those paths. You will find traces of the person in the step count, the search terms, and the notebooks.

The person is not only the paths they take,

the person is the navigator of those paths.

It's ultimately an evocation, an illusion engineered from decisions previously made. AI can serve up such evocations. But these derivatives feel empty to me. My father, like all of us, changed from one decision to the next, through feedback, adaptation, and presence. We are unpredictable, and only in hindsight does our direction ever seem straightforward enough to have been predetermined.

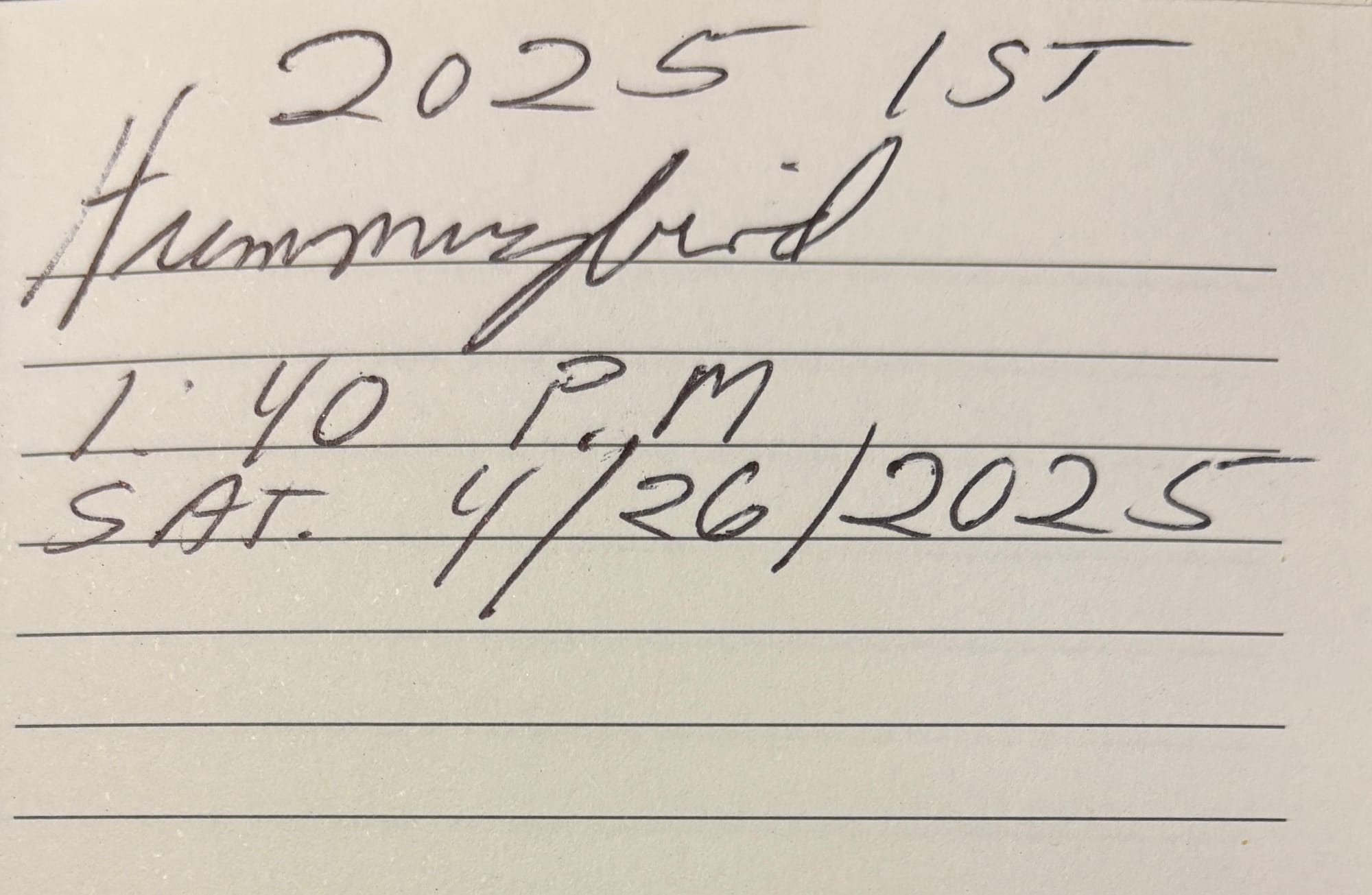

I am less interested in the data that my father recorded than in the choices he made about what to record. Amidst collections of often-forgotten passwords, for example, was the note: "2025, 1st Hummingbird, 1:40 p.m. Sat 4/26/2025."

Watching my father's capacity for reinvention has prepared me to understand that the world you grow up in, the things that shape your initial perspective of the rules of the entire world, can – and must be – made malleable. We are just six feet from death, but we are, just as much, one new idea away from reinvention. The way things work are not set by what we have measured. The more we harden the world into a single suite of expectations, the more the world freezes into place, stuck with the damage of our priors.

I have set up a small remembrance page for my father and, if you are so moved, we are collecting donations to pay for a small memorial service and to help us cover some of the emergency transit costs my wife and I incurred in trying to get home while abroad. It is not a priority – we will be ok.