Searching for Posthumanist AI

Large Language Models are fundamentally anthropocentric

Nothing can be known

without being channeled

through some creature’s senses.

— Jack Forbes

I see “anthropocentric arrogance” thrown around as a slight against AI skeptics, but rarely by people as vocal about the role that trees, caterpillars and fish could play in any expanded framework of kinship.

So I’m skeptical of AI “believers” telling us we’re arrogant for centering human culture above a machinic intelligence — when these machines conveniently speak our languages, tell stories like my stories, and see only what engineers tell them to see.

I am more open to the “stories” of birds or fish or mushrooms than that of large language models. LLMs are a dispersed reflection of a certain cultural mind — while other creatures are compellingly distinct.

Anthropocentric thinking is a meaningful problem. It exists in an entanglement with a whole host of concerns. Of course, focusing on human communities make sense. We should engage in conversations and find solidarity in ways that help humans flourish.

At the same time, we need to move beyond human-centric ideologies to survive as a planet. To that end, post-humanism suggests not a replacement of humanity but decentering it: putting human health on equal footing with the health of forests, rivers, and the air. Given the interconnectedness of these things, post-humanism is not so far from human-centered. If our air, forests and rivers are healthy, it’s more likely that our kids will be healthy, too.

AI has often been looped into this practice, with its technologies part of the natural-technological-human mix. Technology could be envisioned as a mediator, a means of deepening ties to the natural world, or it could be seen as something “independent” of humankind. “Technology” is a broad term, of course, and individual technologies may do one or the other or some mix of both.

But today’s AI — the large language models that have kept our attention so rapt - are not a technology centered on balance or mediation. On a purely material basis, this is evident in the 250,000 pounds of carbon dioxide emitted when training them. The result of that training is an externalized model of our own language, trained on our own writing: a collection of texts posted to the World Wide Web.

Describing humanism - that which post-humanism is “post” from — Jay David Bolter writes:

Humanism was by definition anthropocentric; humanism as a historical phenomenon drew on a renewed and reinterpreted appreciation for the rhetoric and civilization of Greece and Rome, in placing man (rather than God) at the center of its literary and philosophical project. Modern science beginning in the Renaissance sought to achieve an understanding of the natural world that depended on human powers of observation and reason to uncover universal laws. As a Cartesian thinking subject, man could examine the world and explain its workings with scientific detachment—as Galileo famously put it, in the language of mathematics. This view of man as an autonomous agent, separate from though still engaged with nature, flourished in the Enlightenment.

The idea that today’s LLMs are somehow a movement away from this view of human autonomy seems misinformed. We are encouraged often to see AI as an “other,” with which we must learn to co-exist and even “learn from.” It’s our anthropocentrism, we are told, that leads us to question whether the texts generated by Google might be the work of a sentient creature.

AI is certainly an extension of particular human minds, built in a particular image: at best, an interface with internet-accessible knowledge. But it is not a true connection to something “other.” AI learns from us: it is designed to respond to us, and convincingly. Mistaking that for our own learning — from tools that tell our stories back to us — feels to me like that image of Narcissus gazing back from the pond.

Humans have always had relationships with tools, and this relationship is one justification for treating AI as an “other mind.” We have to work to understand it. But that is a relationship wrought through a projection that is re-internalized. Some suggest that this is the only relationship that happens with anything: that we don’t truly know one another’s minds. I’m sympathetic to that argument, but there is a key distinction. When we find ourselves entangled with animals or natural systems, there is something else there to greet us, gazing back with a parallel desire for mutual comprehension.

To reduce that side of the equation is solipsism. It centers the consciousness of one perception over the consciousness of any other perception. We aren’t isolated individuals imagining deeper interconnectedness with the world. The interconnectedness is there, whether we acknowledge it or not, and it’s bound by our capacity to investigate and internalize those connections.

Part of the reckoning with systems described as “apart” from us — the natural systems of seasons and flowerings, the uniquely structured intelligence of a dog or octopus — is that distinctiveness. It tests, stretches, and demands our empathy, our capacity to listen, a critical assessment of our own assessments and interpretations. We learn from the contortion of our own mental models. While AI may provide some of us the opportunity to practice this — by making sense of gibberish generated by a chatbot, or seeking out the logic of a complex but nonsensical image — there is nothing to “know” beyond the very mathematical models that humankind has invented for ourselves.

Yet, we see many scholars, writers and philosophers putting forth the idea that AI is an inevitability that humans must make room to accommodate.

Michael Levin, a scientist at Tufts, writes on Twitter that:

“One way to think about AI (even current AI, w/ its limitations & impending ubiquity): it's like we've discovered a new life form on Earth - it's been all around us, but undetectable; it's quite alien, but it has some high competencies and many unknown behaviors. Just now, for the first time, we've learned how to communicate with it. Of course everything changes. It's a parallel ecosystem - like a shadow world of cognition next to our familiar terrestrial tree of life.”

While poetic, AI is a not a God or a newly discovered fungus with secret competencies. AI is a series of decisions made by people working at companies to sell product. Mythologies like this are dangerous: they ask us to respect a “life form” rather than ask for human accountability in its design and outcomes. Once something is cast as myth, it becomes even more challenging to adjust: you have to fight to even get people to see what’s behind the myth.

AI is not independent from humans or beyond our own agency. It’s not an always-already state of the world. It’s a bunch of human design decisions inscribed into code, with emergent properties. We don’t owe it anything. It is us, just as nests belong to birds rather than birds belong to nests.

A posthumanist AI would need to be designed from a fundamentally different set of principles and knowledge formations. I can envision technologies that facilitate listening over control: make us more present to the world outside ourselves, rather than more distant from it.

AI will reshape the world, and I am not a skeptic in the sense that I think technologies won’t disrupt our lives. I am skeptical that something like today’s automation will bring us any closer to decentering ourselves from the cycle of destruction and extraction that we’re embedded in. If we look to AI as something more than ourselves, we’re going to deceive ourselves into following our instincts toward our own supremacy — at our own peril.

AI needs us to explain the world, but the world has been there, in the meantime, waiting to explain itself to us. It matters which one we look to for our future.

Things I’ve Been Up To This Week

I have been away a while because I was speaking at SXSW! Alongside Avijit Ghosh, we lead a discussion in a nearly packed ballroom for “Can There Be AI Art Without an Artist?” which looked at the connection between AI art, AI ethics, representation and policy frameworks. Avijit is a brilliant and inspiring researcher and I highly recommend you follow him on Twitter or elsewhere. The talk will be shared as soon as SXSW says we can share it. :)

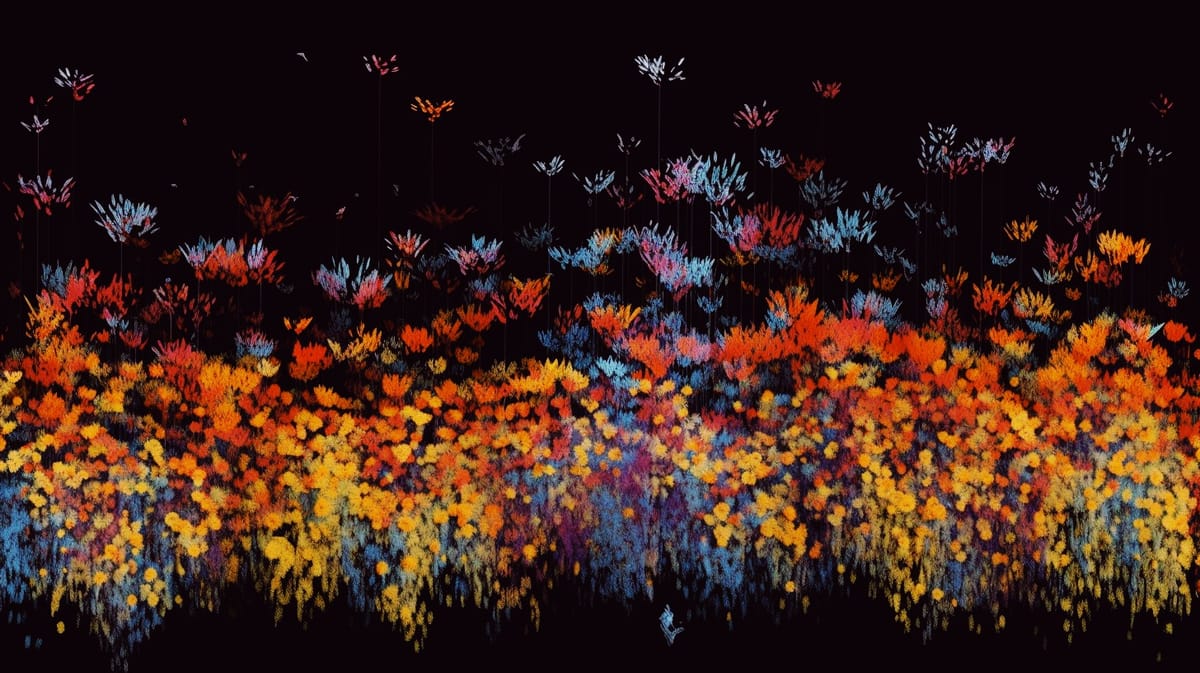

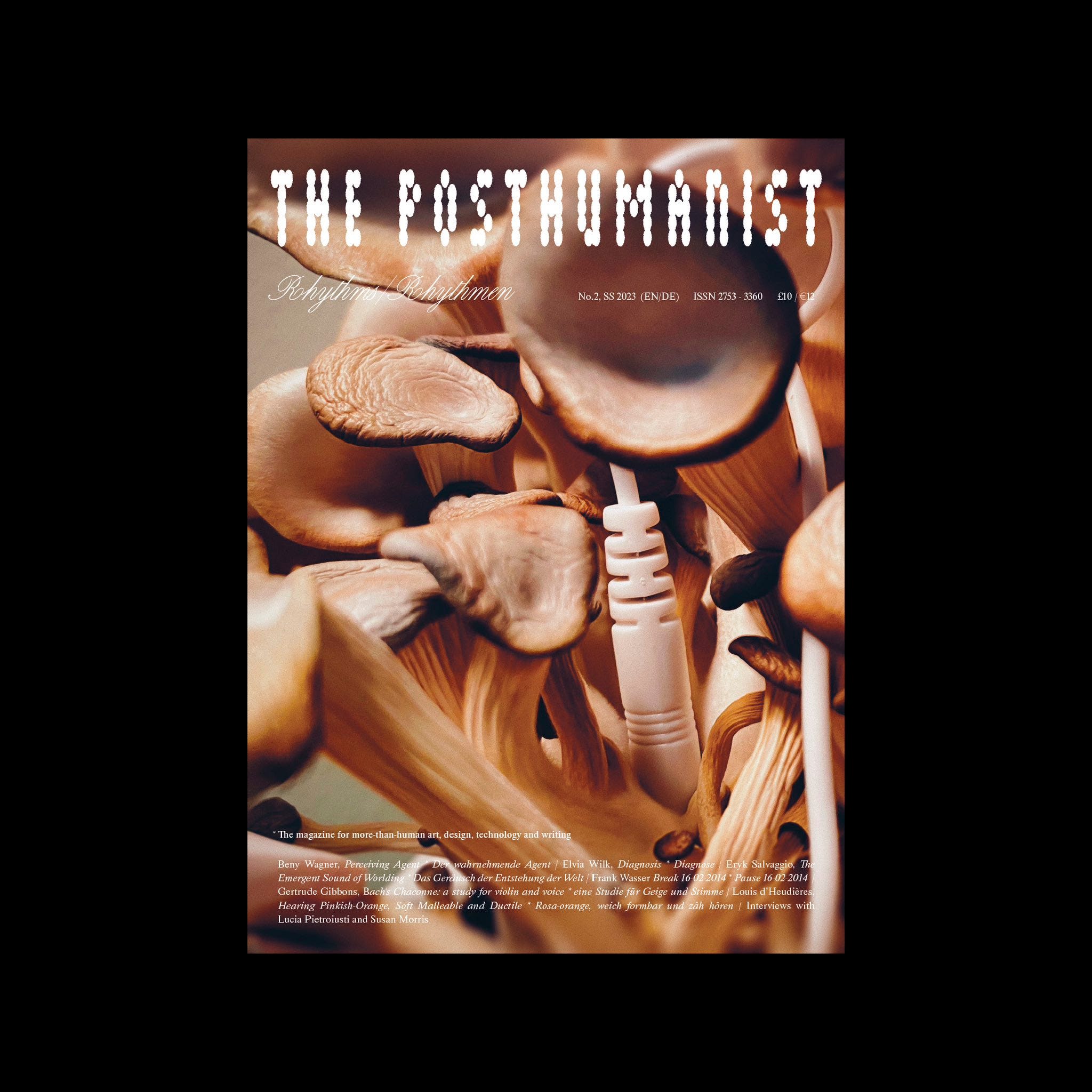

Worlding (link) is also on the cover (and I have an article inside) The Posthumanist issue #2, a Berlin-and-London based magazine exploring issues of, well, post-humanism! You can find out more here.

Thanks for following! You can find me on Twitter or Instagram or Mastodon if you’re looking for more, and as always, feel free to share this post with anyone who might like to read it, or subscribe if you haven’t already!