Shiitake Mushroom, How Do You Know?

You were covered in snow, but you made it now

This week I start on a project, supported by Science Gallery Detroit and in collaboration with Claudia Westermann, Vinny Montag and researchers at the Xi'an Jiaotong-Liverpool University (XJTLU), called “Appetite for Deconstruction.”

The proposed piece is a performance-sculpture, a wood-rot mushroom that dissolves one of the 18 million copies of Guns and Roses’ album “Appetite for Destruction,” with the resulting energy transmitted to a modular synthesizer, transforming the data on that disk into a very different kind of music through a very different kind of means.

A handful of artists and musicians are using electronic sensors to amplify the electrical currents of mycelium. A commercial product, PlantWave, exists for this purpose in New Zealand. Musicians such as Noah Calos (MycoLyco), and Michael Prime have made synthesizer sequences using pulses of electrical current produced as a mushroom digests wood. In these (and our) projects, sensors pick up and carry electrostatic pulses as information from the mushroom, a process known as MIDI biodata sonification, which translates these impulses into digital sounds.

My interest was in the semiotic connection between a mushroom ingesting “data” inscribed onto the surface of the compact disc and that of a digital drive doing the same thing. In this case, we’re producing another kind of information, an extrapolation of the idea, a while back, of “compostable intelligence.” Along the way, the disc is dissolved at a rate of 500 years or so, compared to the 1 million year breakdown of a disk without mushroom assistance.

The question is about how to listen to nature, and what we might learn if we do.

Reading the Mushroom Pulse

In a lovely bit of synchronicity, this week also brought news that mushrooms may have a vocabulary of electrical pulses equivalent to 50 human words: “Mathematical analysis of the electrical signals fungi seemingly send to one another has identified patterns that bear a striking structural similarity to human speech.” That’s from Adam Adamatsky, the computer scientist at the Unconventional Computing Laboratory at the University of West of England who wrote the paper.

Some kind of electrical pulses is firing off at all times in living creatures. Mushrooms use these pulses to send information from one edge to the other in the same way. This meets some definitions of “communication.” The novelty of this recent discovery is that the patterns in these spikes might correlate to descriptive information: the discovery of food, or the fact of an injury, has a specific sequence of pulses. A fungal Morse code, a language of taps and silence: spikes in electrical energy and the space between them.

Mushrooms use these pulses to communicate with themselves across the distance of their bodies. The mushroom is built, famously, distinctly from trees. The mushroom does not branch out from a central trunk, but is an interconnected rhizome, emerging here and there in what we mistake for distinct forms. Those toadstool bits we see emerging from the surface are connected to others: a single mushroom in Oregon covers 3 square miles, and could weigh as much as 200 whales. Beneath the soil there is all kinds of activity and movement.

The novelty in this research is the suggestion that the electric pulse can be described as language: computers transmit information in the same way, as pulses of binary on/off spikes. Mushrooms have better range (they have a spectrum between on and off) but are nonetheless limited to 50 signals, commonly 5-8 minutes long, like a decent ambient electronic track.

The music comparison may be more appropriate than a linguistic one, though the two concepts are somewhat related. In “Emergence,” Steven Johnson writes:

“But what is listening to music if not the search for patterns — for harmonic resonance, stereo repetition, octaves, chord progression— in the otherwise dissonant sound field that surrounds us every day? One tool scans the zeros and ones on a magnetic disc, the other scans the frequency spectrum. What drives each process is a hunger for patterns, equivalencies, likenesses; in each the art emerges out of perceived symmetry.” (2001, p. 128).

So if mushrooms are making and listening for patterns, maybe music is the better metaphor. It’s like talking to my dog: I’ve learned that the dog doesn’t understand my long explanations for why I am going out of the house without her, but recognizes the tone and sonority of my voice and rhythms: the difference between addressing her excitedly about a trip to the park and apologizing for leaving her behind is timbre, not content.

Johnson is talking about machines converting music from CDs into sound, imagining the emergence of a kind of “computer music” that pre-dates our neural-network-generated record labels by about 20 years. But mushrooms have been doing this forever.

Plant Autographs and Their Revelations

“These mute companions, silently growing beside our door, have now told us the tale of their life-tremulousness and their death-spasm, in script that is as inarticulate as they. May it not be said that this, their story has a pathos of its own, beyond any that the poets have conceived?” — Jagadish Chandra Bose, “His Life, Discoveries and Writings” circa 1921.

Jagadish Chandra Bose was a researcher at the University of Calcutta who sought to find connections between all forms of life and non-life, keeping with Vedantic principles for science. He was broadly cross-disciplinary and wrote science fiction, but was dedicated to rigorous scientific analysis. While his questions were inspired by his religion, he was equally committed to the faith of research and measurement. His interest in — literally — “communication and control in the animal and the machine” (Bose uses the phrase “‘continuity of response in the living and the non-living” to describe his thesis), he predates Norbert Weiner’s Cybernetics by about 30 years.

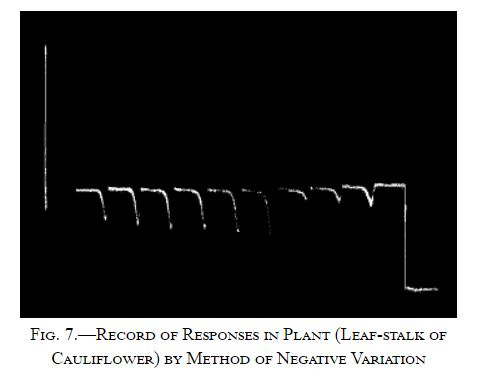

Bose’s research gave us a better understanding of both microwaves (which he discovered while investigating “resting periods” of various metals after stress) and heliotropism in plants. He created a number of instruments to measure electrical response within plants, like this one for a bit of cauliflower.

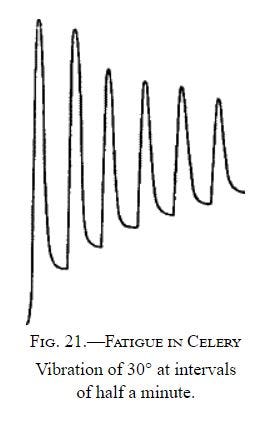

I bring him up because of an experiment that measured electric pulse activity at the moment of death in plants, which caused a tremendous spike. There’s a lot more to this — apparently, this is all explainable by calcium dispersal — but the mechanisms that lead to the embodiment of activity don’t undermine the existence of that activity. That article notes that “Plants are constantly tailoring their responses to current environmental conditions via a complex array of chemical regulators that integrate developmental and physiological programs,” which would also explain human activity from writing poetry to trying to teach cats to tap-dance.

What’s interesting for me is not equivalency between human thought, behavior, motivation, and the like, but the lens through which we experience the expression of natural phenomenon as “other.” While politically loaded, the “otherness” of nature is tied to its dismissal, deprioritization, and destruction.

It is perfectly natural for humans to prefer human culture, but culture is an odd concept, defined mostly by how we agree to perceive it. If we want to listen to plants, we could. And if we did, we might start thinking more carefully about non-human cultural contributions alongside (and within) human ones. Whatever helps us appreciate a forest.

Appetite for Deconstruction

“The wisdom of the plants: even when they have roots, there is always an outside where they form a rhizome with something else— with the wind, an animal, human beings.” — Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, “A Thousand Plateaus,” p. 11.

The artwork we’re making, “Appetite for Deconstruction,” will communicate the overlooked power of mushrooms to remediate plastic and turn toxic BPAs into harmless mushroom-flesh. There are some 18 million copies of this album in the world, all breaking down at a pace of about 5 million years. Remediation in the scientific sense is a way to reverse environmental destruction, in this case by absorbing plastic. Hence the choice of “Appetite for Destruction” as source material — the title changes meaning when considered from the position of a remediating mushroom.

It’s also a remediation of culture: CDs are information storage and retrieval formats, a cultural artefact designed with little consideration of planetary sustainability. There are more CDs in the world (200 billion) than there are stars in the Milky Way (100 billion). The difference is that we will still have uses for starlight in 1 million years.

So how do we re-use these soon-to-be-obsolete artifacts from the lost culture of 80s rock bands? Did we really think we needed to preserve “Paradise City” millions of times over a 1-million-year time span? What if we turned to remediate our culture altogether — rethink what it means to “record” culture and its performances for human scales of presence and perception, rather than planetary ones?

So we’ll turn those discs into a new kind of music as a way to explore the relationships between cultures and waste, for rediscovering the pleasure of the impermanent festivity: music played once and lost. It just happens to be the music of a mushroom, “digesting” our ruins. What could this tell us about decommissioning writ large: data centers storing useless information for decades, with no plans for a sunset, in massive data storage facilities that must be cooled down by heating up the world outside?

I wanted to ask what mushrooms might tell us if we listened, and to suggest music as a perfectly valid form of language and communication. Songs for remediation: an appetite for deconstruction (and rebuilding through listening.)

Synchronicity struck and now we suspect mushrooms might really be communicating with one another through the same kinds of electric pulses I had hoped to wire into an electronic synthesizer. Now we can consider that there is, in fact, a capacity and intent to communicate. The mushroom may indeed possess intent in its communication. Sonification is a way to make that intelligence legible. If the research proves true, then what we’ll hear is more than random data transformed into a signal of digestive success. We may actually hear a transmission! An intercepted one, a recording of a mushroom talking to itself, or humming along to its own thriving.

Our project is designed to reflect on what we might hear if we listened to the natural world, and now, for me at least, I feel like I know just a little bit more about what we might hear.

Things I’m Doing This Week

A Write-Up in the Rochester City Magazine

The Rochester City magazine for news & culture published a very cool two-page spread focused on my visual work, contextualizing it as a lens of critique and analysis. Check it out!

“Party Music” by Party Music

There’s a new release over at my label for GAN-generated music. Party Music sounds like glitch music if it were invented in 1941, or if Peggy Lee and Benny Goodman had listened exclusively to Autechre. Party Music is Graeme Carr Ellis, a “vaporwave refugee,” who turned to AI to play with a new workflow.

This album was produced using SampleRNN, which involves taking whole tracks, slicing them into pieces, and training a model on tones and textures of these fragments of sound rather than a full composition. In this case, the sounds used were the aforementioned Peggy Lee and Benny Goodman, and the results are instantly recognizable and yet completely unfamiliar as music.

I find myself really enjoying it, truly a machine-logic rendering of pop music. If you have always found the stuttering of a scratched CD only interesting, you might dig it. It’s pay-what-you-want (including $0) for a digital download over at Latent Space Records.

Finally, because I will have this song stuck in my head for the next five months.

Thanks for reading! As always, share (or subscribe) to your heart’s content.