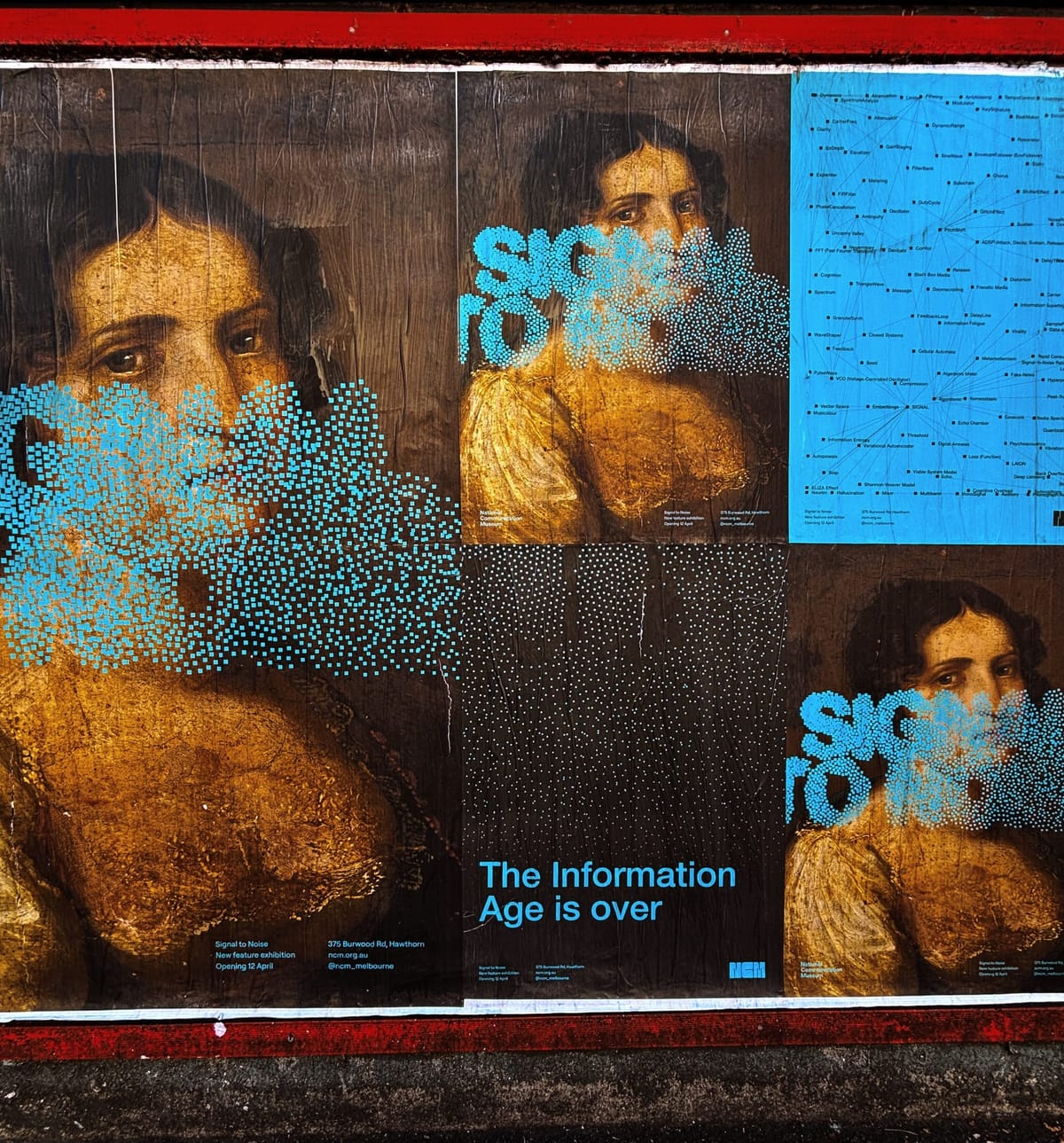

Signal to Noise (and Back Again)

Thoughts on noise, for the opening of “Signal to Noise” at the National Communication Museum in Melbourne.

Our understanding of noise could be traced to a young Einstein, staring at a pond full of pollen 120 years ago. Einstein theorized that the seemingly arbitrary motion of pollen on the surface could be modeled — and in so doing, we confirmed the existence of molecules that moved pollen across these surfaces. Signal to Noise is a similar investigation into what moves beneath the surface of today’s digital pollen, broadcast and sticking to the surfaces of screens and airwaves.

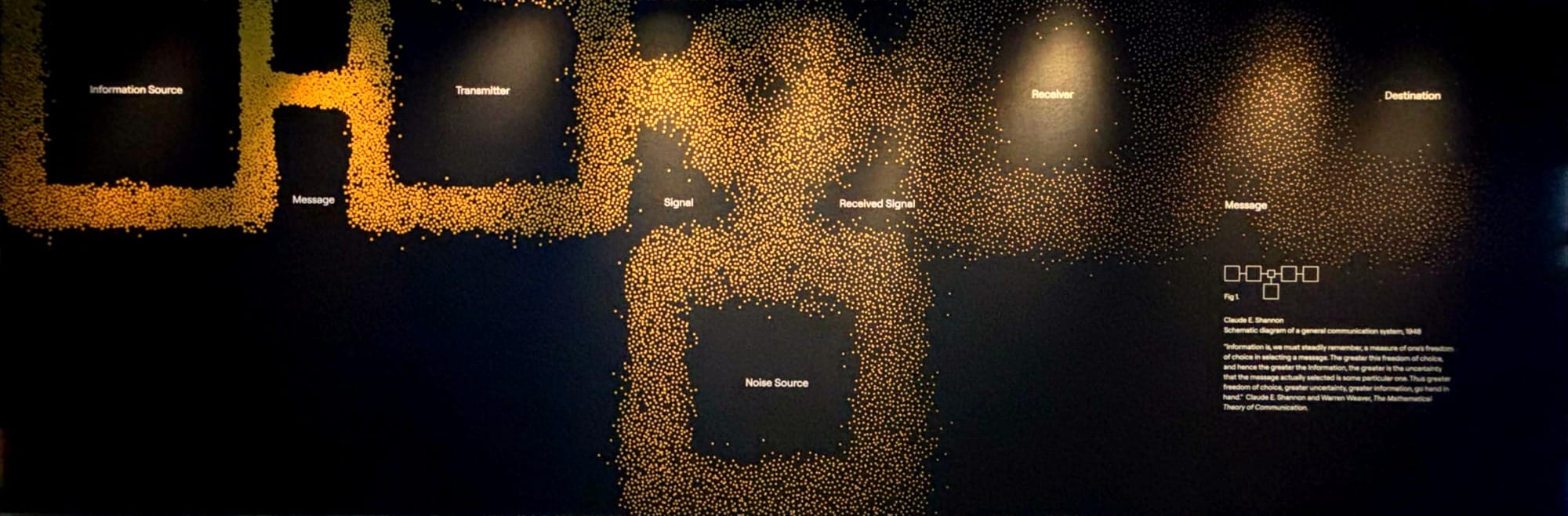

Since Einstein, communication technologies have sought to amplify signals and strip away the backroom drone of noise, primarily following definitions by Claude Shannon. For Shannon, noise arrived from two points within a system. The first was the unpredictability of the information within the channel. The second was unwanted intrusions by the world beyond the system. Such interference, internal and external, challenged our access to information — and the ability to share it.

Signal to Noise examines the history of noise in communication technologies. It includes switchboards for telephones, computers and desktops for the Internet, and the algorithmic restructuring of the social media feed. It is an examination of evolving definitions of noise, and the struggle to keep noise out.

Signal to Noise is the story of an encroaching reversal. As engineers have streamlined the information capacities of systems, accessing information is no longer their central role. Now we are awash in noise. The pond, once lightly dusted with pollen, is now hidden beneath a thick layer. Many of us feel overwhelmed not by our inability to receive information, but by our inability to escape it.

The result: technology is now organized around filtering information out. Information has become noise. So we ask, now, how artists today are redefining such noise – and re-examining its opportunities, metaphors, and risks.

This show is a post-AI exhibition, in that it examines AI not as some radical new future, but as the most recent in a long series of confrontations between the ordered logic of computers and unstructured creativity of human beings. We have been grappling with this tension since the dawn of computation, responding to this logic of orderliness even longer than that.

Artists have been at the forefront of this, because creativity is by definition so richly unstructured, whereas AI is actually quite predictable: it really relies on statistics and straightforward processes to get things done. So there’s a great opportunity to look at how artists make work with computers that strives to break the frame of computational logic.

What is Noise?

Noise is not a man-made phenomenon. The original noise — that cosmic burst of radiation that shaped the universe — obviously predates humankind by millennia. We latecomers have only been able to tune into that noise in the 21st century, thanks to technologies such as broadcast radio and television. Between the channels, the radiation came into our eyes or ears.

The similarity of these sounds to the rushing water of oceans or streams falling over cliffs is a result of the scale and magnitude of activity that water, a frenzy of unsorted sonic frequencies. I live near Niagara Falls, and in a recent visit I took a boat tour to their edge, donned in cheap pink rain gear and unable to hear my partner’s conversation over the boom. In contrast, the white noise of the ocean is differentiated from radio static chiefly by the organization of its rhythms into an ebb and flow: a reassuring consistency imposed upon the roiling chaos by the gravitational pull of our planet.

This meditative quality of ocean sound speaks to the transformative power of organizing noise. The rapid clattering of magnets in the speaker producing bursts of radio static are unorganized sound waves, undirected vibrations competing to shake the speaker. The sound of the radio tuned to unsoiled spectrum is listening to an atom-scaled frenzy, referred to in physics as temperature: the boiling of the tea kettle sounds more like the sea than an ice cube. This circulation of atomic energy speeds up in the presence of heat, and slows down in its absence. If the radio hiss were ever to go silent, it might mean time itself has come to a halt.

Or else it means we did our job of blocking the slow inevitable decomposition of our universe from interfering with, say, the transmission of Chappel Roan’s voice. Our priority as a species is, ultimately, not to hear an immortal roar of the universe but to listen to "Hot to Go!" Noise rudely interrupts our plans, which is also precisely what the slow heat death of the universe is doing to us, too. The ordering of sound into music, a constant tension of repetition and variety, sums up our relationship to information quite well. Too much organization and we get bored, too much noise and we get lost.

Aaron Zwintscher described this dynamic in a 2019 book, “Toward a Possible Noise Politics,” writing:

“Noise is that which always fails to come into definition. The question of noise, and who has the right to define it, is found at the center of the power struggle between succeeding generations, between hegemony and innovation. Noise is found both in the clamor of the unwashed masses and in the relentless din of “progress” and construction of the new. Noise is found in diversity and confrontation with the unknown, the other, and the strange. Noise is in structures of control and domination as well as in the failure of these systems and their inability to be holistic or totalizing. Despite these forms of noise, noise is not a consonance of opposites, but rather a troubled unity, a unity that does not synthesize without remainder.”

In noise, we also see the habits of the European colonial mind: the sorting, the silencing, the steadiness of plan and intolerance of interruption. Cruelty is weirdly fused with a desire for silence, never for cacophony. There is, too, a psychological noise, cognitive dissonance, a chattering interruption of our own thoughts. Silence (that is, denial) in the face of this conflict only amplifies it, forcing deeper responses to suppress. So noise is a means of escaping our cruelty to ourselves; but cruelty to others is a means of escaping "the remainder."

Yet noise is not inherently pessimistic. Noise, the absence of order, is the force through which structures dissolve, liberating categories from distinction, creating a new terrain from which new signals may emerge.

Sidenote: Even Chappel Roan could one day become noise. Years ago, I compiled a Karaoke Songbook of pop music that had been banned by authoritarian regimes or nervous broadcasters (IE: Abba's “Waterloo” was banned by the BBC during the Gulf War, lest it stir up fears of defeat). Censorship of certain noises is nothing new. Charles Babbage, creator of modern computation, spent many of his days calculating the loss of thought owed to street musicians and hurdy-gurdy men whose presence on the streets of London distracted him from his contemplation of future machinery:

“No man having a brain ever listened to street musicians." – Charles Babbage

Telegraphy Lines

Before the radio gave us full sonic access to the universal hum, the hum pestered the telegraph and telephone through interruption and distortion of the voices who boldly assumed we should be able to whisper into long strands of copper and be heard across a continent.

Some endeavored not to interrupt the noise but to listen to it. Thomas Watson, Alexander Graham Bell’s lab assistant, was fascinated by the mystery of whatever was coming through the line. Watson categorized the noises of the ether as it seeped into the empty conduits of undialed connections. Hillel Schwartz takes poetic license to the fact of Watson’s late night listening sessions, imagining those ruminations:

“Was a snap, followed by a grating sound, the aftermath of an explosion on the surface of the sun? Was something like the chirping of a bird a signal from a far planet? What occult forces were just noticeably at work in the recesses of telephonic sound?” (Making Noise, p. 330).

Watson’s interest may have been piqued as the first human to hear electricity speak his name by “varying the density of air” over wires to reshape the voice of Bell, with the request: “Mr. Watson—come here—I want you,” in that Boston laboratory in 1876.

The source of noise in the telegraph was cosmic radiation, but it was also the lack of any stable order in the world in which these signals moved. To create a perfect condition for the technology to operate, vast distances of wiring would need to be isolated from any kind of event. This might be wind rattling the line or trees cutting it completely. It could be overcrowding the line. Solar radiation. Lightning strikes. The struggle between communication and control may best be defined this way, as information theory and cybernetics struggled to make sense of complex systems — while acknowledging that the world would never stand still long enough to see them.

It's appropriate, then, that we had the famous Bell Labs give way to artists who would seek to carve their own names into electrical signals, much as Watson had heard his coming through the phone line. Lillian Schwartz, who has no less than five works in Signal to Noise, worked with computers to create new patterns in electronic charges, writing them into screens or in programs that would cut into metal to create detailed drawings in reflective steel.

The radio, switched on, became a stethoscope into the rapidly beating heart of the universe, but we aimed it inward instead: more useful, I suppose, to listen to ourselves. But artists such as Lillian Schwartz give us dreams of a history of technology in which our relationship with noise was forever inverted.

What if we designed technology to humble us, through perpetually reminding us of disequilibrium, in all its catastrophes and opportunities — a reminder, in the end, that no stability is permanent and striving for it may not insulate us from instability, but diminish our capacities to adapt and respond?

What if the ambition at the heart of communications technology was not to steer our systems away from noise, but to respond to perturbations and disturbances with something like curiosity? How might our relationship to noise — as an antidote to our rush to “solve” and “settle” — become a signal itself? What if we turned away from the insistence upon previously established order — with its fear of unstructured cacophony, of simultaneous and paradoxical positions? What if we designed technology not to provide answers, but to linger, without resolution, on unsettled questions?

In the coming weeks I'll be writing about the works in the exhibition and some of the relationships they speak to concerning noise & signal (and everything in between).

Signal to Noise

Signal to Noise was curated by Emily Siddons, Joel Stern and Eryk Salvaggio. It runs 12 April to 11 September 2025 at the National Communications Museum, Hawthorne, Melbourne, Australia. More details at the NCM website.