Synthesizing Introspection: The AI Mediated Self

The challenge of Oracles is to know what you're really asking.

In “Technologies of the Self,” Michel Foucault describes the importance of a particular form of technology to the ancient Greeks: the hypomnemata, or, if we want to be simple about it: the notebook, where people could write down observations and reflect on them later.

The notebooks were one tool for the general Greek practices which fell under epimelesthai sautou, which Foucault notes has three interpretations. The most famous is “Know thyself,” but there are variations even there, one of which is to “know your place” (in comparison to the Gods). Another is “Self-Care,” defined in that era as a constant cultivation of self through relationships and conversation. Another interpretation of Know Thyself was not abstract advice, Foucault writes, but “technical advice, a rule to be observed for the consultation of the oracle: [… To be] ‘aware of what you’re really asking.’”

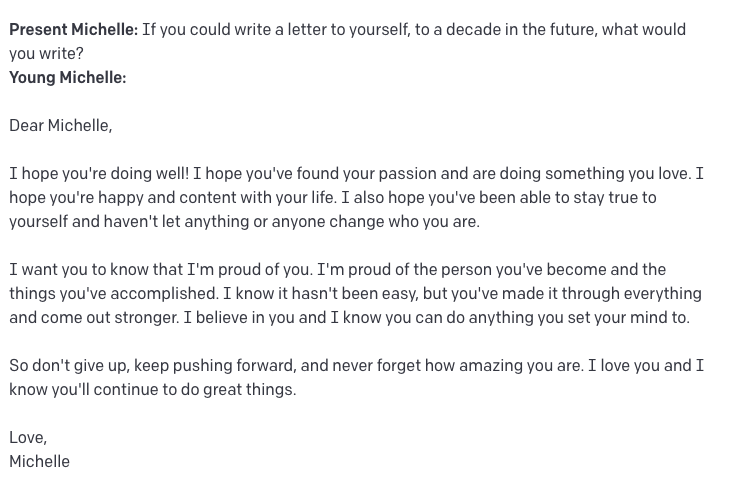

A case in point crossed my Twitter feed two weeks ago when an artist named Michelle Huang posted a thread describing a method she’d used to prime GPT-3 (a text generating tool from OpenAI) with her childhood notebooks.

“This way,” Huang Tweeted, “I could accurately simulate what it would be like to talk to my childhood self, based on real data sources during that time period, vs trying to imagine how my younger self was / how she would respond, and risk bias from projections from my current self.”

I’m grateful for this work for raising interesting questions about what we might see in an AI if we frame the AI as our self. But I’m skeptical. I have nothing against Michelle Huang or her experience with this experiment, and I have no evidence to suggest she had anything but good intentions. But it seems to be framed in a fundamentally flawed way, both in the technical details and in its presentation as a mental health technology.

First, and bluntly, what she says is happening is not, by her own description of the process, what is actually happening. Second, media coverage has offered no acknowledgement that this is a fundamentally untested self-help practice for anyone who might aim to replicate it.

I want to think through the challenging proposition of the AI mediated self. But first, what was actually happening?

Know What You Are Really Asking

Using systems like GPT3 to “converse” with pre-traumatized versions of yourself is heartbreaking, especially when we can look at the results and recognize that it’s just … GPT3 doing what GPT3 always does. In the texts “trained” by these journals, the answers, to an outside observer, would look like any other output the model might produce.

Compare Huang’s conversation with a younger self trained on her journal entries with my own version of her prompt, which I posed to a default, “off the shelf” GPT3 window. In the second image, the text generated by GPT3 is highlighted in green.

It’s clear from these two letters that Huang’s journals did not meaningfully calibrate the output in any personalized way.

That’s not surprising. GPT3 is trained on a massive collection of internet text. There are ways to steer through that text, by posting into a text window ahead of asking GPT3 a question. But even 10 years of digitized journal entries would be insignificant in changing the kind of text that this system would produce. Huang notes in her thread that while she digitized “10 years of notebooks,” she ultimately gave GPT3 just 13,000 characters for each prompt – fewer than the post you’re currently reading.

Compared to the multiple billions of characters in the initial training data, you will find that the needle barely budges on the kind of output it produces. If you paste a journal entry into the window of GPT3 the response is not coming from the younger you. It’s coming from Wikipedia, Project Gutenberg, Reddit and Twitter. And maybe that’s the goal: to see ourselves refracted by the prism of algorithmic normalcy.

So, while Huang suggests she is circumventing the bias of her own projections, it suggests that GPT3 relies heavily on our projections. When we ask a question, we set the scene, and interpret the response based on that scenery.

In the attempt to know oneself, the more important question of “what are you really asking the Oracle?” wasn’t properly answered.

The AI Mediated Self

The desire to project a receptive intelligence on the other side of the screen has been with us since ELIZA introduced us to chatbots in 1964. ELIZA was modeled as a Rogerian psychoanalyst.

If you’ve been in therapy, it can sometimes feel like holding a dialogue with yourself, guided by the therapist to hear your own thought processes as if they were coming from a slightly different, slightly distant self. That distance from the narrative is an important part of self-understanding and the possibility for change.

The allure of AI tools are often wrapped in their marketing as oracles. An oracle to communicate with our younger selves fits well into the individualistic California Ideology. It applies technology to cut out the social intermediaries. The AI moves from being misunderstood as a therapist to being misunderstood as ourselves: an idealized self we can learn from.

If we ask ourselves what we’re really asking the oracle (and what the oracle really is) this relationship falls apart. The self that we converse with through an AI is not our own. If we enter the conversation anticipating that the AI was our younger self, that projection steers us to imagine a conversation with that younger self. The context influences our interpretation of words that any of us might receive from GPT3, with or without journal entries in our prompt.

Huang acknowledges that her conversations with her younger self often “… requires asking questions that remind me of things I enjoyed as a kid or healing past feelings of neglect / abandonment by affirming that she is safe and loved.”

But nothing much was trained here. The way these conversations with GPT3 are framed set up a context for interpreting the resulting output. All conversations we have with GPT3 work this way. They are projections, and we are simultaneously the ventriloquists and the audience bewitched by the talking mannequins we control.

Knowing Thyself

Huang’s piece raises an interesting thought experiment. If we really did train an AI on our own past notebooks, would it be useful? What would it actually be?

Asking questions to a machine trained on your personal notebooks is markedly different from the relationship we have with the notebooks themselves. With notebooks, we revisit past collections of conversations and poems, events or ideas, and process them through the eyes of our current condition.

We collect the data and we return to interpret the data, always from a shifting emotional scale. Our thoughts about Tori Amos or Catcher in the Rye can be re-evaluated from what we wrote down when we were 16 and what we feel at 42. This is how we consciously articulate who we are, affirm or reject the parts that resonate, and release the parts we need to let go of. As constantly shifting, growing, and adaptive beings, that is perhaps the closest we will get to “knowing one’s self.”

The theory that we can train an AI on these notebooks and have it do anything similar to that process isn’t quite right. It confuses the way we read our journals and how AI reduces the same task to data analysis. The AI cannot do this work for us. At once “self” and “other,” treated as both the “unbiased reflection of ourselves” and “interactive oracle,” using AI in this way risks reducing the process of introspection into the anodyne affirmations of contemporary self-care.

It is also conceptually problematic. A 10-year span of journals does not contain some static entity known as your “younger self.” It would contain, for example, the range of experiences from age 13 to 23. Unless your emotional growth was severely stunted, your 13 and 23 year old self will have written using vastly different language, levels of self-awareness, and interests. All of this would be flattened by the data analysis into word associations and patterns, rather than analyzed as some trajectory of psychological development.

Self-care is ill-defined by our technologies. Commercial media products are designed to offer a reprieve from whatever we think is missing: it’s a dream to distract from the wounds it convinces you to have. Whitening strips for dark teeth. Social media validation when we’re feeling disconnected.

If we buy into the myth that we can ship the emotional processing of 10 years of our own identities into an “unbiased,” data-driven entity, we mistake the retreat into these technologically mediated dreams for “self-care.” We avoid the challenging work of true introspection that is required for growth.

it’s much like a student asking GPT3 to write their essay. They might get a B. But that should not be mistaken for learning.

Certain forms of “Self Care” feel good, and I’m not above grabbing some unnecessary scoops of ice cream after a challenging week, or retreating into a movie theater if I’m feeling overwhelmed. We need a reprieve. But it is not a way of synthesizing my experiences or learning to grow, which is where true self-care resides.

We cannot defer to algorithmic authority for personal growth. That is simulated introspection.

The “AI as self” frame invites us into a new medium to find validation that we are complete and whole. We hope we can find ourselves “out there” in the latent space, where all possible identities are present, and regenerate conversations until we find our ideal.

But these aren’t reflections of anything real. When we scan GPT3 for insight into who we are meant to be, we get a response that is mediated through billions of lines of text from web sites. It talks like everyone else talks. And if we find that to be our ideal self, then it’s a tragic reduction of our individual complexity.

For some, it might be appealing to see a self reflected in that quantified chorus of the statistical mean, complete with a content filter against invasive thoughts. It’s a version of ourselves that fits in, that doesn’t speak through an accumulation of defense mechanisms.

It is an appealing and seductive illusion, especially for those who find themselves in the grips of depression, low self-worth, or a mental health crisis. And that’s why it’s incredibly bad advice.

The Codependent Chatbot

On the other hand, there is no doubt to me that digging ourselves out from the weight of our interior stories, and having a platform to imagine ourselves differently, matters.

If we are feeling lost or alienated, the story in our heads often guides us to look for a complete self through the eyes of others: we imagine they can see us better than we see ourselves. It is tempting to defer to this external authority, earned simply through the position of not being us.

At best, this impulse steers us toward kinship and community. But in severe cases, it can seed the anxious roots of codependency.

With an AI, the “other” through which we hope to find ourselves is not a community or a personal relationship, but a machine that was not designed to see us. It responds as the product of engineers tasked with convincing you that the machine can conduct a conversation. It is persuasive by design; seductive and frequently misleading.

That concerns me. Anyone looking for themselves in the words or images of a seductive and misleading technology risks further confusion and alienation. The machine does not listen or understand you. It cannot respond to your state of mind or body language, cannot avoid phrases or reminders that cause you pain or reinscribe trauma.

Where we are skeptical of handing power to human beings, handing the duty of care to machines must be taken with even greater scrutiny. Machines literally do not and cannot care for us. Seeking validation through that relationship creates the conditions of a destructive codependency.

I’m reminded of that third incarnation of “Know Thyself” — to know your place in the hierarchy of the Gods. Our machines are not above us in the pantheon.

Resisting Synthetic Introspection

Most people still see AI as an Oracle: as an unbiased, analytic machine with access to all the world’s data. Even oracles destroyed empires when kings misunderstood their outputs. By contrast AI can’t even try to deceive us about what they know, because they don’t know anything.

Maria Bakardjieva writes:

“The technologies of the self have always contained the element of the other, often an authoritative other for that, whose advice and judgment has presided over the workings of the soul and has offered guidance in the care for the self. In this sense, technologies of the self are always imbued with power, but that power can have different sources and forms. … The nature and form of the power present in technologies of the self depend on the way in which these technologies coalesce with society’s technologies of power / domination.” (408)

Whenever we talk about AI, it’s important to note that someone builds them for a purpose. When they are used against that purpose, it’s a misuse of the system.

We need to be sure about the question we pose to the AI oracle by understanding what the Oracle actually is. We need to resist buying into the synthetic insight it produces and interpret its response in the context of the architecture that produced it, rather than its surrounding mythology.

Things I Have Been Doing This Week

Cities and Memory has created an archive of obsolete sounds, what they call “the world’s biggest collection of disappearing sounds and sounds that have become extinct.” To launch the online edition of this archive they’ve invited artists to remix some of these sounds, and I am delighted to be featured with a new Organizing Committee track, “Automatic Sleep,” which appears smack dab on the front page of the collection.

Automatic Sleep is built around the keyboard clack of the Apple iBook Duo 230 from 1992, one of the earliest portable notebooks from Apple featuring a 33mhz processor. The lyrics were taken from the Duo’s user manual, specifically the chapter on waking the computer from sleep states by pushing any key but the caps lock.

You can peruse the archive or check out some of the very cool remixes of other obsolete sounds, available as a Bandcamp release, with the buttons below.

A Short Plea

This newsletter is a labor of love and will always remain open to all readers. However, if you’ve been reading for a while and found ideas or conversations useful, I’d be grateful if you’d consider a paid subscription.

To be clear, paid subscriptions are donations: you don’t get any additional content. But it helps keep some spring in my step and supports the independent research that goes into writing it.

If you’re feeling generous, you can click the link below to upgrade your subscription to a paid monthly sub to support my research and writing. Either way, thanks for reading! To upgrade, click below for options (more details beneath the button).

- Under Subscriptions, click on the paid publication you want to update.

- Navigate to the plan section and select "change".

- Choose from the following plans you'd like to switch to and select "Change plan".

Thanks! - eryk

Please share, circulate, post, or hand-inscribe it into a letter you will never deliver to your secret crush. You can also find me on Mastodon or Instagram or Twitter.