Syzygetic Cartographies

Exploring maps, paths, and unexpected alignments.

If you’re going to design collaborative spaces, you need to know what collaboration looks like. Last week I was invited to contribute a short class activity for design, interaction and architecture students at the California College of Arts’ Future of Work program. We wanted to encourage reflective thinking about how interpersonal, interdisciplinary collaboration works.

So, I turned to Pataphysics. It's a 19th century proto-Dadaist art movement, a “parody of science.” If science aimed to unearth “universal” truths, Pataphysics aimed for a science of exceptions and radical possibilities. In this science of the imagination, the study of “unlikely alignments,” or syzygies, was central.

Syzygy: an unexpected, unusual combination of two or more things, phenomena, or concepts. Taken from astronomy: parallel alignments between the planets, moons, or suns.

In astronomy, Syzygy is the alignment of celestial bodies. In Pataphysics, it refers to the imaginary science of overlaps and coincidences. Alfred Jarry called them “puns in real life.” When different meanings come together in a single point, that’s syzygy.

Artificial intelligence systems are prone to this kind of thinking, but by mistake. A language model does not intend to mistake “apple” the fruit and “Apple” the company, but it does — and so it accidentally arrives at puns about eating computers as the source of original sin (which is why it’s so good at generating Fluxus Performances).

For me, syzygy describes words, ideas, and practices shared between people that haven't met. Susan Leigh Star gets at these common connectors when she writes about boundary objects. We all see things through our own lenses. How do we learn to see and understand other lenses, and come to find points of union and difference?

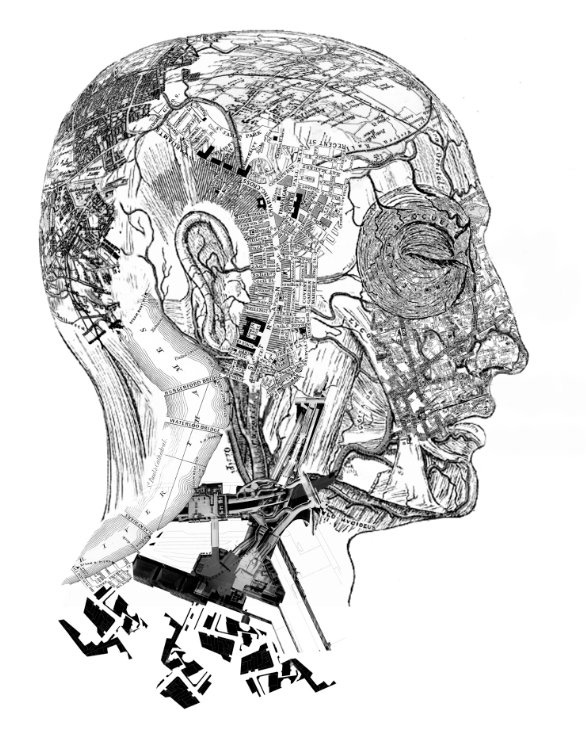

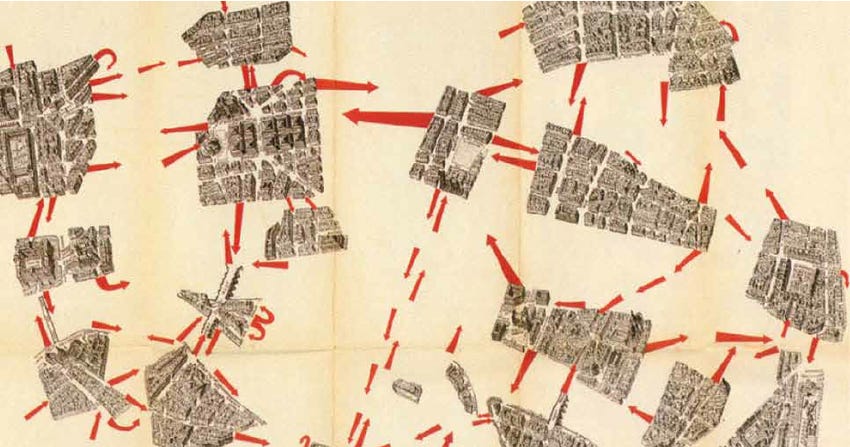

Maps are one way. They chart space and declare territories for common reference. Years after the pataphysicists, the Situationists came and invented psychogeography: maps that trace the paths and terrain of a city, but in a deeply personalized way. These maps are collages, juxtaposing and resizing neighborhoods, landmarks, and random streets according to specific meanings and relationships to those spaces: a science of the particular.

Debord described the benefits of the practice this way:

“The production of psychogeographical maps, or even the introduction of alterations such as more or less arbitrarily transposing maps of two different regions, can contribute to clarifying certain wanderings that express not subordination to randomness, but total insubordination to habitual influences.” (1955)

I wanted to invert this relationship between inner and outer spaces. I came to something called “syzygetic cartography” — making and sharing maps of our interior, psychological spaces, rather than physical territories. Crucially, this is a collaborative exercise: it can’t be done alone. The territory you map must be a shared one. By comparing our notes to others, we find the unexpected alignments between the interior, imaginary geographies of our inner territories.

Nothing breaks down a series of habits more than pausing to describe them. It seemed like a good way to challenge how students think about collaboration, and to bring new ideas into play that might inform their work.

This is a pretty surreal practice, and like much surrealist stuff, the assignment for CCA was deceptively complicated:

- In groups of four, students would draw a map.

- The map would be a drawing of a collaborative process.

- That collaborative process would be the act of drawing that map.

Basically, drawing the trail as you walk through the mountain.

Turns out, Applied Surrealism has its benefits. First, students practiced talking about how they approach collaborative processes. They discovered that others may have different ideas and expectations, so they learned to communicate and navigate personal strategies as a shared terrain. They practiced negotiating and explaining what a situational collaboration looks like for individuals and then as a group. Many learned that what they had assumed to be innate and universal was just one in a suite of collaborative strategies. Finally, in presentations, they could see the breadth of strategies used by others.

***

This weeks links are different ways of tracking pathways, making/unmaking maps, and looking for unexpected alignments.

Things I’m Doing

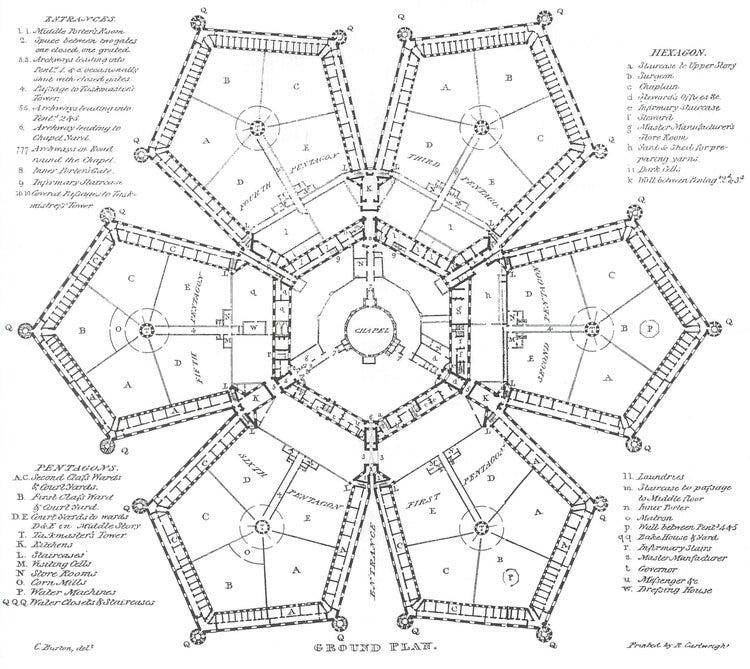

Nobody is Always Watching You: From Big Brother to Big Data

My keynote talk to the New Commons Project at UM Farmington is now available as an essay! There’s a link to the video presentation, too. I explore the trajectory of surveillance technology from the publication of George Orwell’s 1984 to today. It’s meant for a general audience.

Things I’m Reading

If you appreciate my takes on things, go read from the person who taught them to me. Genevieve writes an excellent essay connecting the history of technology through cybernetics, the role of arts and imagination, and the future potential of machine learning.

- Psychogeographic Cartographies

Larissa Fassler

A great example of some contemporary psychographic artmaking that incorporates lived experience into imagining urban spaces. Fassler’s drawings document “crowds and riot police, posters and placards, extracts from newspapers and information signs about U-Bahn upgrade works, … the temperature of the breezes that run through building passageways; the corners upon which the sound of squealing bike brakes is a frequent occurrence; the smell of freshly butchered meat from a shop meeting the smell of newly mixed tar from the road works.”

- Desire Paths

David Farrier

“Where the designed way is often straight and rectilinear, the desire path bends and flows. It offers grace rather than instruction.” David Farrier explores the tracks made by people and animals when they are intent on finding a way, rather than following one. This essay examines the allure of finding new footpaths and how to read the trails they leave behind.

- All the People on Google Earth

Jenny Odell

Visualizations of Google Earth imagery with the imagery taken out, leaving only human figures on white backgrounds. Thinking about the artist’s eye for isolation and removal as a way of thinking about overlays, maps, and the alignments that can be found in “random” patterns.

- Repellent Fence (or en Español)

Postcommodity

An artwork presenting an indigenous view of borders, particularly the US-Mexican border. “The purpose of this monument is to bi-directionally reach across the U.S./Mexico border as a suture that stitches the peoples of the Americas together—symbolically demonstrating the interconnectedness of the Western Hemisphere by recognizing the land, indigenous peoples, history, relationships, movement and communication.” The work is beautiful but so is the process of engaging people to create it.

The Kicker

Hank Beyer and Alex Sizemore are making computers out of locally sourced materials, including ice and honey.

Thanks for reading this week. I’d love to hear your ideas, suggestions, or random commentary — e-mail me or find me on Twitter.