Terms of Engagement

Social Media and the End of Play

My dog is blessed with excellent communication skills. If she needs something — whether it’s to play, eat, go outside or just be held for a few minutes on the sofa — she comes into my home office and sings.

It’s distracting by design, but she’s also drawing me into an emotional entanglement. If I can’t respond, I feel like a monster. I’m frustrated by bad communication, but also by good communication met by indifference.

Communication requires good transmission and good reception. If there’s interference between those points, it’s easy to forgive. A signal sent without care, though, or a careful transmission ignored by the receiver? It hurts.

It’s not about radios. For example, if I’m out in the world and hear a child crying — I’m talking about those devastating existential wails, the kind that make people leave restaurants or start an online culture war — an intrusive thought appears: “I get it, kid.” It’s not dismissive, not a joke. It’s sympathy. I relate, somehow. It’s a tic, always phrased in the same way.

The howl, from a baby or a dog, is expressing a need beyond words. It’s a call for empathy: “I know you don’t understand me, but I need someone to interpret this and respond anyway.” It is frustrating to want a toy lamb you’ve dropped and be unable to reach it. Frustration is amplified when you are unable to express your need to those who could effortlessly resolve it. When this is your entire universe, the realization that you cannot express yourself to those you depend on for survival is the origin story of profound existential horror. You are alone, but you depend on others.

In a healthy system of reciprocity, kinship and care, we might learn to internalize safety. For a range of reasons, not everyone does. My dog, perhaps, is not in a pit of existential dread. She depends on me, and so I must be dependable. In a world of interdependencies, the inability to communicate is scary. To deny empathy is, I suspect, intrinsically hard.

Nightmares

Melatonin bottles do not warn that deep Buddhist doom-dreams are a side effect, but there’s a 10% chance that I will be visited by some cold-sweat terror vision of a universal indifference to the eradication of my worlds and their traces.

If you buy into Freud, dreams are like shadows cast by some internal psychic fire. They take the swirly patterns of sparks behind the eyelids and we weave a purely indulgent story around them. Whether we indulge in selfish desire or pure fear, those stories are gifts. They’re a way to see the stories we wrap around literal nonsense when self-censorship filter shuts down. The stories hiding behind the way we interpret the waking world.

In my dreams I shout, but lose my voice. I inhale air deep into my lungs for a primal howl and hope it will send the chaos scattering. I scream at some distant and inaccessible symbolic universe. But nothing comes. Outside that dream, there’s a bedroom, where neither my partner nor the ever-sensitive dog down the hall hear more than a weird moan. C’est la vie.

When I wake up I struggle to remember or even articulate the existential terror I was trying to spook away by yelling at it. The real terror was the thwarted shout. It’s a recurring fear of communicating to indifference: my life as an externality of some uninterested, self-sustaining system. The scream is a child’s plea for attention.

“I get it, kid.” A desire to be heard through indifference. Ego, but not narcissistic; entitled, but not toxic. In the dreams it doesn’t come.

I remember these nightmares when I contemplate the unhealthy relationship I have with social media. Staring into the face of the abyss, and all that. It would seem that this internal story of an indifferent world has latched on to my relationship with social media.

I have been getting better, and now I can examine it and talk through it. And I can point a finger, hesitantly, on the pulse of this psychological feedback loop. Along the way, I hope I can express something more generally about the way we design technology in the 21st century.

The Feed

Social media is built on the principle of fusing desire into a series of pings: “I’m here, do you see me? Will you respond?” This puts you and I at the center of the network, and puts everyone else into the feedback position. You see the innate contradiction already.

Nobody wants to be an externality of the universe. The demand for acknowledgment, recognition, acceptance and kinship in our lives is the healthy response to the dark void of space. We live through one another, sustaining a relationship in defiance to an unconcerned churn. But we have also organized ourselves in ways that empower us to act as agents of indifference.

Social media’s call-and-response is the system that moves the engine forward. Interaction should be part of relationships, rather than the input prompt in a feedback loop for self-sustaining content streams. We feed and we are fed, but we’re never nourished.

The structure of social media relationships is an economy of affection, given and withheld. I get and give likes, and I get and give anxiety about those likes as I make decisions on offering or withholding them. It makes convenient the effort of interpersonal communication. It’s made an ever-present, but bad friend. I don’t talk to people I consider important. The information is there.

A computational regime that encodes all of this into a UX for relationships and connection is clearly disturbed.

Social media companies even describe this communication as an act of war. They track metrics of “engagement.” Engagement is the point when hostile parties are forced into conflict: a military engagement. Or else it is an obligation: a marital engagement.

To be engaged also means to participate. But we don’t call them “participation metrics,” do we? That would be intuitively wrong. We don’t participate when we “engage.” We click and go, hoping for symmetrical engagement under a low-key but ever-present threat that our actions will be met by indifference.

It’s small. But we do it a lot. Children do it even more. I worry that it is teaching us the rules for a game nobody asked to play.

Play

I don’t know what to make of James Carse — his book, Finite and Infinite Games, seems at once over and underrated. It’s not full of new ideas but useful articulations of old ones. One of them is playfulness as a state of consciousness made accessible by safety, but rejected in the presence of “serious” threats and risks.

Playfulness, he says, emerges from a shared agreement to enter a space of ever-changing rules invented with the purpose of playing the game forever. This state is the state of human thriving: invention. Hanging out.

Play is at odds with the “serious,” the rules which must be followed to survive. Survival is not playful, but playfulness emerges when survival is not a concern.

To terminate playfulness, Carse argues, is evil. Murder ends all play: the creative, imaginative world within a person is brought to a permanent stop. You also end play by stripping away the right and power to imagine. You end play by creating a context of anxiety and fear through punishment. Authoritarian power and abusive relationships emerge when playfulness is replaced by fear, enforcing the seriousness of a single player’s rules instead of shared play in a collaborative game.

Carse suggests that these conditions are engineered. But it seems to me that some play-killing systems emerge from, and are sustained by, indifference.

The opposite of play might be found in the idea of “code.” When code is indifferent to play, it ends play. Play is open ended, malleable, loose, ever-changing. Code is a series of constraints. Code contains “serious” rules, which terminate play if they are broken, regardless of their intent. Facebook is a social structure enforced through digital code, and digital code is serious.

Contributions to code-constrained play are acknowledged only when expressed in a particular language, which is determined by what the code can comprehend. We are limited by the affordances of the technology. Playfulness with the boundaries of this code is punished rather than rewarded because the code won’t work.

The Noise is You

Algorithms boost content according to rules of engagement — of conflict, of war, of obligation — rather than rules of play. Instagram boosts the color of flesh, rewarding images of exposed bellies, arms, and chests into your feed. When you post, the computer analyses your content and scores it before any human does.

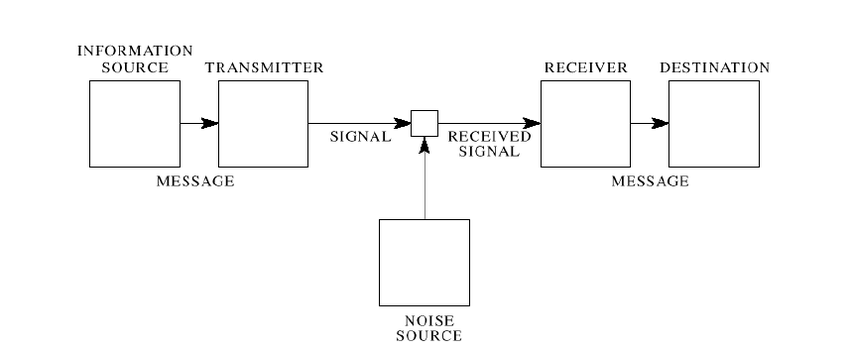

Landscapes go nowhere, but skin gets you somewhere. What you see is mediated by this algorithm. This is the “engagement metric,” and it runs between you (the transmitter) and the people who care about you (the receivers) — or “followers,” in the algorithmic parlance. The algorithm moderates, imposes order, constrains play.

“The consequences can be severe. In December, a Brazilian artist tried to advertise one of his Instagram posts. The request was denied on the grounds that the post contained violent content. It only depicted a boy and Formula One racer Lewis Hamilton. Both were dark-skinned. In April, a yoga teacher was denied an advertisement on the ground that the picture showed profanity, even though she was only doing the side crane pose. She is Asian-American.” - Édouard Richard, Judith Duportail, Nicolas Kayser-Bril and Kira Schacht @ AlgorithmWatch

As an artist and a writer, I spent years bitter and confused about why so few of my friends could be bothered to “like” a link to a new article, blog post, or artwork.

Then I realized that the prioritized message is transmitted by the social media algorithm. The receiver is the passive viewer of the algorithmically curated content.

This is not explained anywhere on social media sites, and so it would be easy to mistake algorithmic indifference for human indifference. But the indifference is not that of the people who love you, but of the people who built an algorithm that prevents the people who love you from receiving your signal.

The architecture of these communications channels is designed to filter “noise,” but the noise is you. It’s your grainy pictures of blowing out a birthday candle in a dark kitchen, de-prioritized for darkness. It’s the link to a new drawing you’ve made, photographed without enough blue for the algorithm to find it of interest to some aggregate of data it considers to be “everybody.” It’s the picture taken at the top of the mountain you just climbed by yourself, weighed less because the algorithm does not like landscapes without people in them. It’s the link to a news item about your work, or a new web project, that nobody sees because links take them off the central server.

I don’t think “the universe” has it out for me. But we’re born into a system of social and cultural affordances. Social media systems concentrate those affordances further into coded architectures: serious rules and restrictions. Certain paths are available to us and others are not. Some things are heard and others are not. Some of us have leverage, some of us do not.

Playfulness is not the point. It ought to be.

Waking Up

I get it, kid.

We’re born as empty little adaptive beings looking out, bright eyed, for some semblance of rules to follow to ensure we are cared for. We mimic the behavior of the beings who pick the lamb up and hand it back to us. We look for others. We have an innate but malleable sense of kindness alongside a preverbal need to be cared for, with needs we have no language to articulate. Our attenuation to others is how we survive.

Many things accumulate to build up thick layers of crud over this early conception of co-reliance and interdependence.

Algorithmic indifference is one architecture of harm to these relationships, to self-esteem. The code enforces a logic that rejects play.

Let’s be clear: the “metaverse” doesn’t exist. But the ambition they have for this new world is steered toward deeper immersion in the illusion of play while constrained to the same central scripture: the mediation and constriction of human interaction into a series of traceable, predictable, and hijackable pings.

We build systems for individuals, then call the aggregate results “social problems.” The terms of engagement should not be left to emerge undirected through the affordances of these systems.

It’s impossible for me to ignore my dog’s attempt to communicate with me. Successful communication is an overlooked miracle: open-ended, evolving, ever emerging. It’s built on trust, reciprocity, and clarity.

Designing systems that ignore the complexity of communication, burying trust and clarity behind opaque code, leads to systems that end the stream of playful interaction. We replace it with a narrow, inhuman set of compelled rules. We’re coerced to relate to one another through these terms of algorithmic “engagement”.

Indifference to those outcomes by designers of these systems is, increasingly, an act of hostility. It is engineering aimed at the end of play.

Thanks for reading! If you got this far, feel free to subscribe or share the post. Circulating these newsletters is always appreciated!