The Art Machines of Zagreb

Looking back at New Tendencies, an exhibition of computer art from 1960-1971.

The gold standard in referencing cybernetic art — roughly speaking, art that is built on interactive feedback between humans, animals, and machines — is the 1968 exhibition, Cybernetic Serendipity, which premiered in London as the first interactive computer-art show in the UK. The show went on to the Palace of Fine Arts in San Francisco and heavily informed the hands-on, “interactive science” philosophy of the Exploratorium.

While groundbreaking, and one of the best exhibitions of the work underway at the time, I’ve been skeptical that it was the first.

You might argue that another exhibition, with a very different set of priorities, took the mantle. New Tendencies, opening in Zagreb from 1960-1971, and a corresponding magazine, Bit International, were dedicated to the idea of breaking down the lines between research, science, and art. The exhibition was within a decidedly socialist framework: "art as research and the establishment of new forms of distribution beyond the art market, which should be accessible to every man."

To this end, one of the prizes was for works that could be distributed to be reproduced in homes, not as an art object (which would have been capitalist!) but as DIY art projects. An emphasis was placed on the work being reproducible: this would democratize art away from the exclusivity of the art market, and more toward accessible aesthetic experiences.

The exhibition, imagined to be permanent but ever-evolving, was set inside a Zagreb department store. While computer-based works were included throughout the years, in 1970 the exhibition moved entirely to computer art for "New Tendencies 4." A partial catalogue remains. This catalogue includes a number of manifestos for cybernetic art, all quite political in nature, and oriented toward the artist as a researcher.

The Anonima group’s manifesto is a particular favorite:

On the other hand, the work and its catalogue seems quite defensive of its position as research. In Margit Rosen's book about the events — "A Little-Known Story about a Movement, a Magazine, and the Computer's Arrival in Art: New Tendencies and Bit International, 1961-1973" — there is a transcription of the exchange organizers had about the selection of the 1970 jury. In it, five organizers debate whether an artist, or art critic, should be involved at all, given that the aim of the exhibition was to "abolish the difference between research and art." For that reason, it would only be researchers on the jury — rather than an artist, they opted for a "graphic design expert or architect" to fill the fifth seat, because an artist “would not let anyone else get any work done.”

I’ve been reading The Two Cultures, CP Snow’s book about the segregation of science and humanities, wherein he argues (in 1959) that the scientist and researcher were undervalued compared to artists and humanists — at least in the sense of the respect of the general public. Artists were more famous, he said. They found more prestigious work, and their names were connected to their products in ways that wasn’t true of scientific research.

I wonder if this same sense influenced that defensiveness among the New Tendencies crowd, with the artist “giving up” their privileges as artists to work under a research regime. Other aspects of “research-ifying” the artists included early demands for anonymity and an emphasis on the work being “objectively produced” as an answer to a research question, rather than the romantic or subjective whims of the creators.

This strange push for an “objective” form of scientific research, declared to be at odds with the “subjective” minds of artists, is of course impossible. Objectivity, as Donna Haraway writes, is “the god trick of seeing everything from nowhere,” the idea that work can be carried out by a person who is absent as a person from the research they conduct. As a provocation, New Tendencies is interesting, but they blur the line of art and science in a way that preserves this myth of the “impartial” scientist.

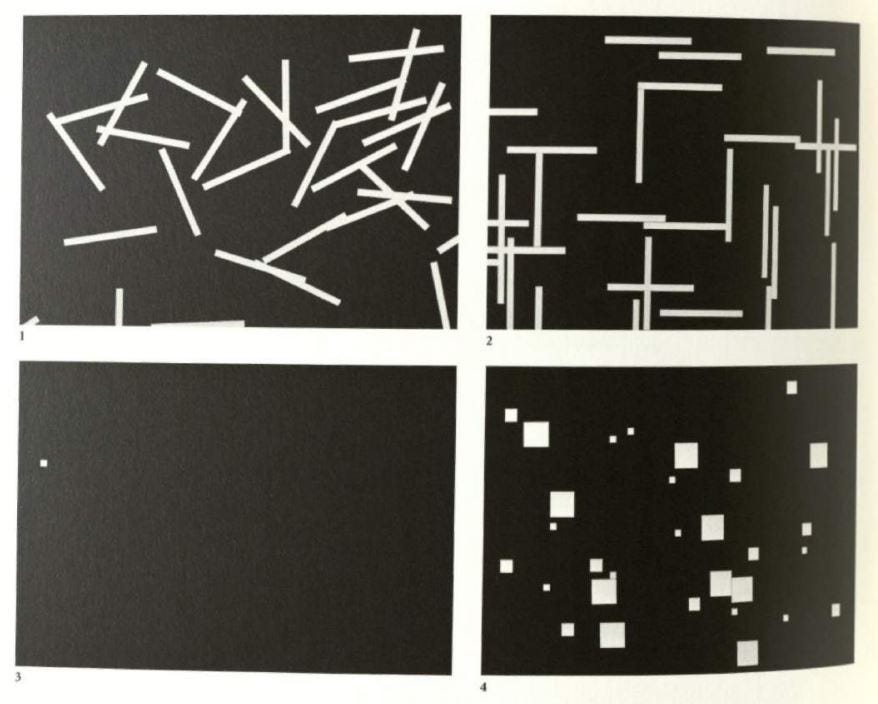

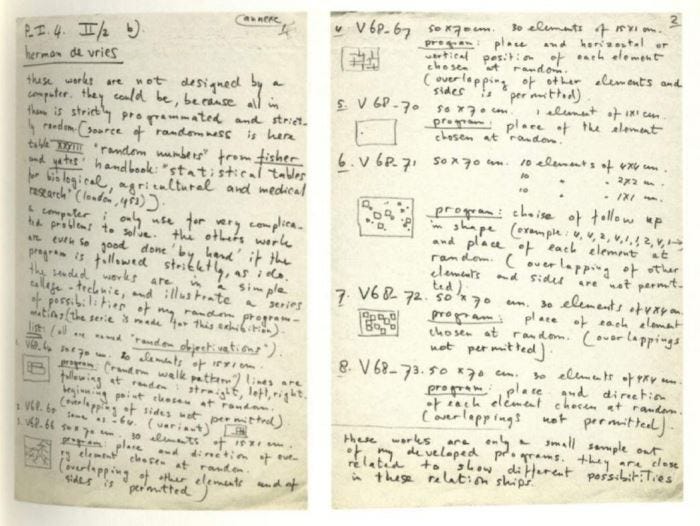

For this reason, New Tendencies is a hell of a lot less fun than Cybernetic Serendipity, even if many of the selected works overlap. Nonetheless, there is some clever work, such as herman de vries' Random Objectivation, four panels of art and a handwritten text that serves as a kind of artist’s manifesto for the next century: "These works are not designed by a computer, but they could be," followed by instructions for writing the program that could reproduce his own handiwork.

The good bit about the “research” influence of this exhibition is that the catalogues include a detailed description of how each work was made, so they could be reproduced by anyone with access to the materials. The call for entries also banned computer programs submitted in isolation, emphasizing that the works must have “an interaction with aesthetic reality.” This lead to an emphasis on outcomes — the products of computation — rather than on computation as an artform.

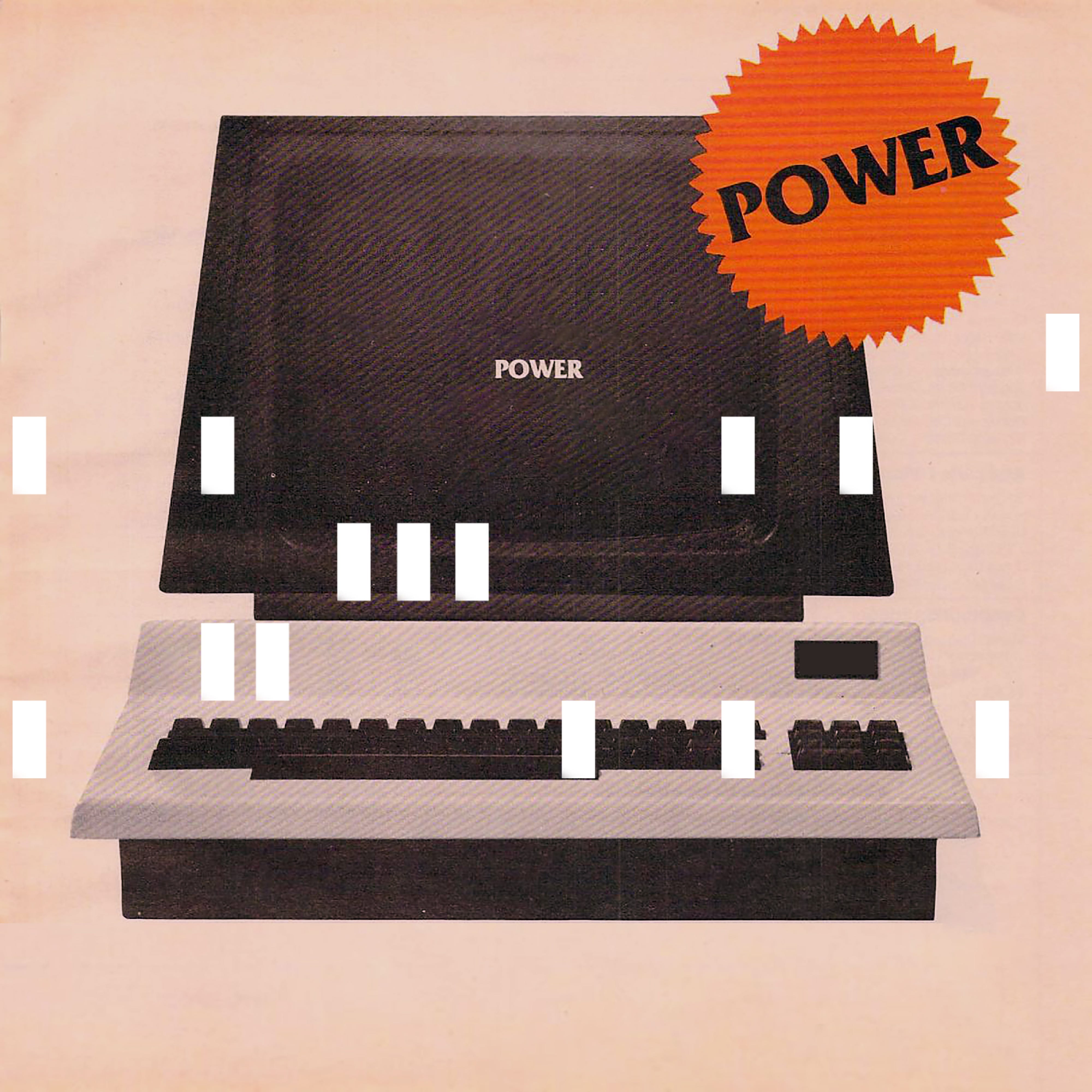

The academic and socialist politics of the catalogue also informs questions about what all this technology is really doing for (or to) us. Abraham Moles, for example, was heavily active in the group. His contributions include things like describing exactly how AI-generated images might work, in a way that, it turns out, is exactly how AI-generated images do work. But he also, in his role as an “early warning system of world-future,” presented a compelling warning nearly half a century before the Googles, Facebooks and Cambridge Analytica would make the rest of us wonder:

“Machines are discreetly conquering our world, i.e., the world of our thoughts. It is certain that machines, the producers of energy, are not too discreet. The car is the most obvious instance. We notice, even too much, its presence, we take it into account in our plans, we make speeches about the industrial revolution and man’s power. But, it is the data processing machines that from now on are determining how we shall act, and this is to such a degree and in such an underhanded way that we are justified to speak about a secret revolution which is taking place without its participants being aware of it.”

It all has me thinking about another question: Why cybernetics? I think these older computer works are little windows that don’t really tell us how to do things, but help us rethink what things we want to do. These are works that seem relatively simple to understand, and demystify some of today’s nebulous, interconnected computer problems. The way these works are described show real nuance about how they work.

In this video, for example, Michael Noll — who’s work is in New Tendencies 4 — discusses his work on computers choreographing ballet. If you were to ask anyone in 2021 “what is a computer program?” I think the answer would be very different from Noll’s — “a computer program is a way for a human to convey an intention to a machine.” But once you start thinking that way, you start to see all kinds of new potentials and possibilities. I sense that today’s computers are too opaque, our visual sphere too overwhelmed and over-developed to cut through. We lose focus, as designers, on the things we actually need to do.

When I look at these old works, that curtain lifts, and these systems and their possibilities become a bit clearer.

Shout out to the Node Center’s course on “Curating in Arts, Science and Technology” run by Isabel de Sena.

Things I’m Doing This Week

I have a new three-song EP, “California Ideology,” released as The Organizing Committee over at the legendary Canadian netlabel, Notype.

The tracks were built around a foundational 1995 essay exploring the origins of Silicon Valley thinking: a blend of hippie eccentricity, libertarian individualism and techno-utopianism. The songs take that essay as a starting point for some machine learning models to spit out lyrics, which I set to music with varying degrees of help by algorithms.

“In the presence of God, we hear electro-acoustics.”

I hope you dig it!

Things I’m Reading This Week

###

The Anthropocene is Overrated

David Sepkoski

The idea of the Anthropocene — that we are in a geologic phase of earth’s history which will be permanently scarred by humankind’s presence on the planet — is a compelling one for framing climate change. But it might be doing more harm than good, argues Sepkoski: “The implication is that people, as a whole, are a problem” — in ways that diffuse responsibility and action.

Proponents of this view argue with some justification that whatever their source, the technological innovations that have produced major changes to the Earth’s climate and environment—carbon dioxide emissions, industrial pollution, artificial radioactivity, deforestation, etc.—have been global in their impact. That is certainly true. But it’s also worth asking whether the responsibility for these consequences—and, perhaps more importantly, the agency in responding to them—is distributed fairly.

###

Automation or Meaning? Socialism, Humanism and Cybernetics in Etarea

Maroš Krivý

Thanks to the Zentrum für Netzkunst exhibition on East German Cybernetics, Soviet cybernetics has been top of mind lately. This paper looks at the Socialist approach to smart cities as envisioned in 1966. Based on a design concept that put “meaning” at the center of the city, it also applied cybernetic theories of equilibrium to create space for machines, nature, and communities to thrive together. Etarea was just south of Prague, and somehow managed to openly sneer at the Soviet-planned economy’s lack of humanity while remaining ideologically aligned with socialist principles. This was par for the course for Czechoslovakia. And, much like its cybernetic-socialist cousin, Project Cybersyn in Chile, the project ended when tanks rolled into the streets.

Etarea was situated amidst a sprawling recreation zone with rudimentary cottages, cabins and camping sites, epitomizing the kind of compensatory recreation that was spurred, according to Lakomý and Nový, by deficient socialist housing. Čelechovský wrote that disfiguring Prague’s hinterland with ‘tasteless cottages’ resulted from the legitimate desire of city dwellers ‘to live in a healthy environment for at least one day a week’.

If you like what you’ve read, please share it! And if you’ve just found the newsletter, please do subscribe. I publish one issue every Sunday.