The Audience Makes the Story

Puppetry as Dream Analysis for AI Anxiety

This is a discussion between Camila Galaz, Emma Wiseman, and Eryk Salvaggio, collaborators behind an experimental workshop linking puppetry and generative AI that took place at RMIT in Melbourne this summer at the invitation of Joel Stern and the National Communications Museum. We met online to discuss what emerged from Camila's workshop: personal imaginations of AI made physically manifest into puppets.

Earlier this year, we spent five days in residence at the Mercury Store in Brooklyn, joined then by Isi Litke, among a full house of puppeteers and actors, trying to form a methodology of AI puppetry and develop exercises to make this metaphor into a mix of performance, workshop, and critical AI pedagogy. That was translated into a Zine, "Noisy Joints," which was sold around the US, Europe and Australia this summer.

The workshops are intentionally messy, aiming to map out an imagination dominated by tech's portrayal of AI through grand narratives and myths about "sentient agents" and "intelligent machines," as well as through interfaces that convey the machine as an eager worker.

None of the industry's myths leaves much room for individual, critically oriented sense-making. We wanted to reintroduce the human to this imaginary. In Melbourne, participants weren't given a traditional puppetry lesson (that is Emma's domain, and Emma wasn't there). So the improvisations were "wrong" by almost all professional standards, but offered a window into how people conceive of AI in their heads (and how they make it move).

The workshops are designed to be a disorientation from the highly intellectualized and abstract relationships we have with AI. With puppets, we have to turn the abstraction into a physical form, and then imagine how it moves. Other instantiations of this workshop examined bodies, glitches and "shortening the strings" — creating a direct relationship between our bodies and the AI's training data.

The Spectacle of Strings

Eryk Salvaggio: Camila, you were the only one in Melbourne. How did you introduce it to folks?

Camila Galaz: Very briefly: Ideas around puppetry and puppet metaphors particularly often use the idea of strings. In our zine, we call this the spectacle of strings. The strings in puppetry reveal how the puppet is puppeteered. If we look at the people controlling these strings, we acknowledge the process and the labor behind the animation of an inanimate object versus feeling like it's coming alive all on its own, like magic.

When technology like Generative AI conceals its workings, it sometimes feels like magic. And in that magic, we risk losing our sense of autonomy as users. It becomes easy to see AI as something with a mind of its own, rather than something shaped by human choices.

Eryk Salvaggio: The strings are hidden.

Camila Galaz: We're wondering if there is a way with Generative AI to reveal the strings, to reveal the puppeteer's presence as a reminder that the illusion is not sorcery, but craft or choreography directed by ourselves. This is your line: "We approach Generative AI as a puppet with strings that are so long as to render their operators invisible." But humans are the puppeteers — human bodies, whose data ultimately shapes AI's outcomes.

Humans are the puppeteers — human bodies, whose data ultimately shapes AI's outcomes.

When we frame AI as a puppet and ourselves as the ones pulling the strings, we reveal AI as choreography. Movements are shaped by training data, by thumbs, by traces of us. The strings are always there, stretching from our clicks, images and words. AI responds to an extremely long string, so long that the sources of its motion, the data that animates this puppet, set the human puppeteers so far behind the curtain that we may forget they exist at all.

AI video generation tends to produce images of strings whenever it makes a puppet. But then we quickly introduced another form of puppetry, bunraku, in which the performers touch the puppet directly and are always visible on stage. So instead of having long strings where the puppeteer is perhaps behind the scenes, here the puppeteers, as a team, physically support and move the puppet on the stage, without strings. The labor is visible and the process is transparent.

While maintaining the mystical nature of bringing life to a puppet, there is also a demystification of process made visible through the work of puppeteering. We wanted to question how we render process, material and labor toward a different quality of relationship, a genuine demystification of how technologies work. How do we make ourselves visible as the operators of generative AI? How do we invert the relationship projected through AI's interfaces to more firmly center AI as the puppet and humans as the labor behind it?

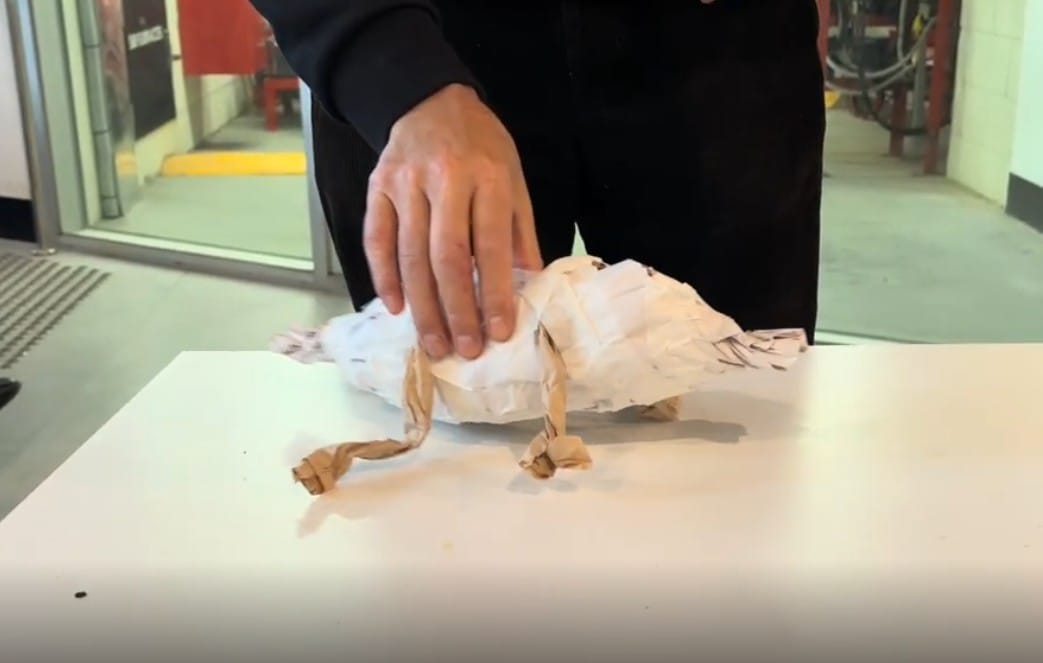

So then we made some paper puppets. The idea was, we all have an imagination of AI - I'd like to see how you're all imagining it. How do we make AI a puppet that isn't drawing on the tropes of robots and automatons, but on the somatic and emotional feeling of using generative AI as the puppeteer? Where we, the puppeteers, remain visible? How could you make this process legible, like in bunraku, instead of concealed, like in a magic show?

Eryk Salvaggio: And so in the workshop, people made a puppet without strings, and then there's the puppet show where they're meant to be present with the puppet.

Camila Galaz: The first thing was 'what is your imagination of what AI is for you, your relationship to AI’, and make something that represents that. So for example, I basically put a halo around my puppet's head. It's like a human, but it has to have a structure to hold itself up.

With the actual performances, I asked people to think about themselves as the puppeteer and the puppet as the AI, rather than trying to make it seem like the puppet's alive. One of the significant differences between our imagined AI, our conception of AI, and actual systems is that AI often feels abstract, distant, or immaterial. In contrast, puppetry is immediate, physical, and embodied. When we make a puppet, we can see and touch the process of bringing something to life. We become aware of the labor and decisions that animate it.

We didn't use AI technology in this workshop at all. We were talking about AI while we were making, and that physical process helped think through things in a different way.

The Automated Cringiness of Decision

Eryk Salvaggio: This workshop is literally just asking people to deal with things that don't really make sense physically, but then they have to make them make sense. AI is so intellectual. We often have an intuitive, vibe-ey understanding of how AI works, but we can overestimate the completeness of that intuition. Asking people to express it is awkward, because we're trying to articulate something in a form that otherwise didn't have one. How do you make these ideas physical through craft and movement?

Emma Wiseman: Paper puppetry workshops are a tool that has been passed down to me as a way of teaching puppetry, specifically bunraku style, three-person puppetry. So you're pushing people toward a long technical history. Bunraku is also virtuosic: what you're going to get at in a workshop is never going to achieve the idealized form of Bunraku-style puppetry.

But people operating puppets is always exciting, especially for their first time. By jettisoning that overhanging context to explore making a puppet as a single person and manipulating it as a single person, we're no longer moving towards learning a technique.

Instead, it feels exciting to let that go and close the aperture on the relationship between what it is to make something and what it is to move something. Having human hands on the puppet makes this idea of labor completely transparent in Bunraku. There aren't strings. That's what makes it super relevant for the AI conversation.

The group aspect of bunraku is also evocative of how generative AI utilizes huge swaths of data. It's being created out of many, channeling energy into this one thing. We're drawing inspiration from bunraku, but a workshop where groups puppeteer something could shift the focus from historical labor divisions to collaborative teamwork, breathing as one, and exploring these elements and techniques. That specific connection between the many coming into the one.

And also the cringiness of the decision. Embodying something and making a choice is awkward, but also great. AI just kind of has to go for it too, you know? Often it's just, like, so awful and weird. But it is the thing. You press go and it has to make a video.

Eryk Salvaggio: A lot of people who work with AI often rely on the fact that it can make that cringy decision for them, I think. They can take creative risks, because they don’t have accountability for those decisions. It’s like watching bad improv, which can actually be quite amazing — people have no idea where to go, and it all breaks down, and the struggle is what becomes valiant. AI doesn’t struggle with that which makes it a bit less valiant, to my mind, but that can explain how we react when it does something "surprising."

With AI, the decisions are pretty constrained and directionless. The data sets are built by multiple people, whether they like it or not, and so they're steered by people into millions of directions. On the flip side, every little data point becomes a way of maneuvering the video. And in bunraku, especially with untrained participants, there's a steering of the puppet as a group that perhaps mirrors this steering of the AI system, even though we’re so far removed. Dispersing decisions.

Dreams of Living Sausage

Eryk Salvaggio: I think two people in the workshop made platypuses.

Camila Galaz: One of them was introduced as a sausage — the AI is like a sausage because a sausage is like a lot of cut-up bits of meat, essentially.

Eryk Salvaggio: So is a platypus! It's a beaver with a beak. A living sausage.

Camila Galaz: The idea was, like the outside of the sausage, AI has a thin skin and then that makes it look like a thing, like a sausage, but the inside is full of random stuff. So in the video they ripped open the middle of the sausage to show it's all made of paper. The point was that it's all made of the same stuff.

Emma Wiseman: And that was in response to your prompt, not only to make a puppet that is your imagination of AI but also asking them to reveal the labor in how they were manipulating it. That made ripping apart the puppet so intentional. A lot of times people default to violence or sex or dancing — ripping apart or throwing the puppet does happen in this kind of childlike, playful way. But here it was a thoughtful response to your prompt.

So many of them chose to kill their puppets.

Camila Galaz: I brought this up in the workshop to them as well because it was so stark that so many of them chose to kill their puppets in some way at the end. And when we were doing the Mercury Store workshop, I remember having that conversation during the show-and-tell evening. So many people in the audience said they just wanted it to die and end its suffering. Like, 'why is it alive and here?'

They're a bit monstrous, so many people threw them off the table at the end or had some ending that involved their demise. But also it could be the idea of a puppet show or performance that needs an ending. If you don't have a plot, you're just flying this around and at the end, they'd throw it.

Emma Wiseman: Like undergrad contemporary dance pieces, where at the end everybody collapses, and that's it. There are ways to demonstrate the end without words, and it can feel both "first thought, best thought" and primal.

Camila Galaz: I also don't know if anyone took their puppets home. We were left with a lot of paper puppets to get rid of.

Emma Wiseman: Does that have anything to do with it being an imagination of AI?

Eryk Salvaggio: Well, yeah, I think there probably is more, even if people weren't thinking about it and people just start mashing paper together while thinking, "what is AI?" And then if you've made an insect, even if you have no idea why, you've made an insect. It's like puppetry as a Freudian dream analysis about AI anxiety. What you do with the puppet is surfacing evidence of an imaginary relationship, especially if you have no idea what you are trying to do with it.

What you do with the puppet is surfacing evidence of an imaginary relationship, especially if you have no idea what you are trying to do with it.

Puppet Design is Interface Design

Emma Wiseman: It's exciting to see how the choice to manipulate the thing is so intertwined with the thing itself. In bunraku, you're trying to create the puppet to fit a particular division of labor and a manipulation style. Here, your physical relationship with the puppet is also being devised.

Eryk Salvaggio: Here people were designing the puppet and then inadvertently designing an interaction with the puppet. In the sense that how we imagine something shapes the way we interact with it, like the user interface.

Emma Wiseman: That would be a question. What comes first for people: the form of the object, or how it moves or is moved? And how intertwined are those considerations?

Eryk Salvaggio: My assumption is that the icon comes first. Then the instrumentality of it comes almost as an afterthought. You make it then figure out what it does. (Which is sort of how we got AI to begin with).

Emma Wiseman: The puppeteer's gaze is so on the puppet in these videos. That's another thing we struggle with in a bunraku group. We often see beginning actors who look out and ham it up, putting their face out to the audience. We're always trying to say, 'no, look at the puppet.' A puppeteer cues the audience to watch a puppet by watching it themselves.

Eryk Salvaggio: Some puppets resembled a stick bug to me, and I've noticed a pattern emerging in the creations of others, which are animals that combine elements of other animals. Platypuses, stick bugs, they're kind of AI-native species. A bug that looks like a stick and a duck that looks like a beaver. These are animals that double as hallucination artifacts.

Camila Galaz: I felt at the time that the stick bug was more inspired by the “biblically accurate angels” with a million eyes and all the wings, and those freaky creatures from mythology.

Emma Wiseman: The vibe is also limited to what you can do with paper and tape. It's always going to be a little bit like Frankenstein, given the materials.

Camila Galaz: We had two angler fish.

Eryk Salvaggio: I thought that was a narwhal. This is just gonna be me interpreting other people's AI instincts, but, like, a narwhal is another AI native animal, right? It's like a unicorn horn on a whale.

Emma Wiseman: This is like the “Go home, evolution, you're drunk” tumblr page.

Eryk Salvaggio: It's a genre of unexpectedly pieced-together animals. The angler fish is still that. What's that lantern doing on a fish's head? We can see people reaching for these parallels to nature, especially weird, "drunk" nature. It’s a really smart intuition, I think! A reference to the weird mutations of culture.

Collapse as Technique

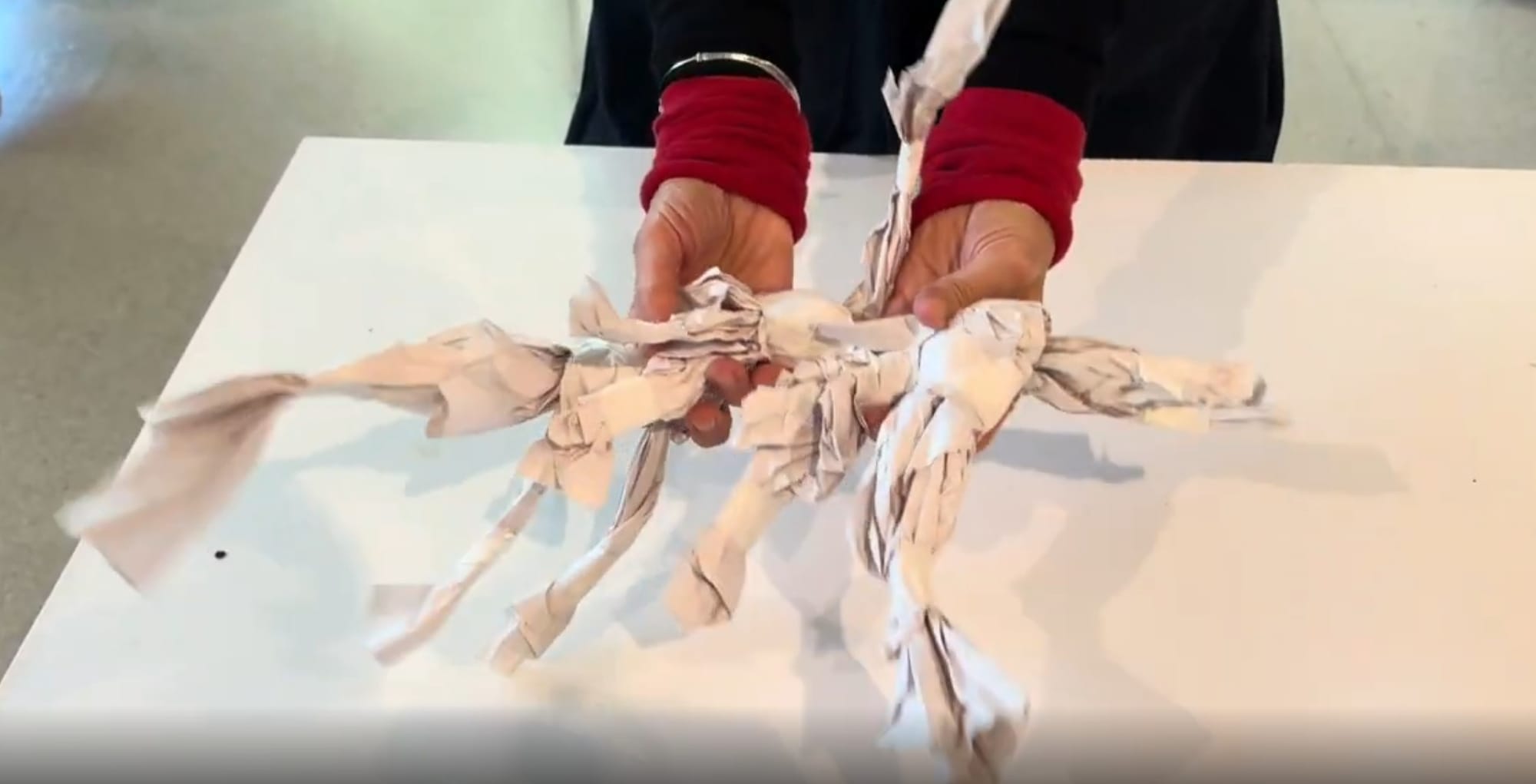

Camila Galaz: There was a rabbit that had a lot of legs, so many that it couldn't stand up, but the goal had been for it to be very stable. Then we had one puppet that didn't have any tape and it was all woven together. She's holding it and then it opens and moves, but it's a weaving.

Eryk Salvaggio: She described it as a whole that collapses. It comes together, only to collapse again. We often hear the word "collapse" in discussions about the end of AI. "Model collapse," for example, where the AI becomes overtrained, or the economic collapse of the industry or the collapse of the business model.

We often hear the word "collapse"

in discussions about the end of AI.

That word "collapse" seems to be how we imagine the death of AI. Emma, you said violence, sex, and dancing are what people do with puppets and mentioned undergrads falling to the floor at the end of their dance performances, too, also a kind of collapse. An exhaustion of other ideas, paired with a lack of space to continue.

So when people have to end a performance, they might think about the end of AI in ways that match the popular conversation. Explosions or collapse. That's how the AI dies, that's how AI ends.

Camila Galaz: It can change based on the interpretations going in. If they use or like AI, their puppet would be different from someone who sees AI as monstrous. But it's interesting seeing people heading toward tropes. AI goes towards tropes.

Emma Wiseman: What would come out with different materials? I worked with a playwright interested in e-waste. We brought in a bunch of old motherboards, wires, all sorts of stuff that was like, let's all make sure we're wearing gloves. We made and operated a giant puppet made out of those things, and of course, the quality of that is so different from paper and tape that you can throw around and lift with one hand.

Eryk Salvaggio: What's interesting about paper and tape is that because it's not valuable, the only thing that is of value in the puppet is the idea. People don't cherish their time with paper puppets! They're very aggressive toward the things that they've made.

Emma Wiseman: But I am really seeing intense concentration and real decisions being made about these motions, even if it is playful.

Eryk Salvaggio: I think if the prompts for the puppet making were like, "make a puppet that visualizes creativity in your community," people would probably not be tearing it apart and throwing it off a table.

Camila Galaz: Initially I was struck by the physical, somatic experience of being able to puppeteer something. But in the end it was the fact that everyone was killing their puppet, which we saw echoed in our original workshop as well. It’s the same feeling we get when we try to make AI create something that's a little off. The uncanny feeling — what is it that we've created? It is a puppet show. It is being moved in a way that we understand through children's play or actual puppetry shows. But it doesn't necessarily have the grounding that those things would have. It meant that things lost some weight, maybe in the same way that AI doesn't have that weight and history.

Emma Wiseman: One of the things we ask in puppetry is, how are these big ideas represented in movement? When I do workshops like this, we'll write a list of action words that have nothing to do with emotion, and then emotions that have nothing to do with action. Puppets can accomplish these actions, but the experiment explores, for example, what love looks like within those actions. All of these emotional words have to be translated into action in some way, when you’re dealing with a non-verbal form of storytelling.

Even if you were doing these action words that have no underlying intention to them, the audience is always going to make meaning or a story. You can't help it.