The Intimacies of Mechanical Things

A conversation with sound artist and writer Bani Haykal

examine the heart of those machines you hate

before you discard them

and never mourn the lack of their power

—Audre Lorde (1973)

Bani Haykal is an artist and musician living in Singapore, whose work explores human-machine intimacies through the media of interfaces, poetry, and sound. Bani’s music can be found on Bandcamp and Soundcloud, and you can find more on his website.

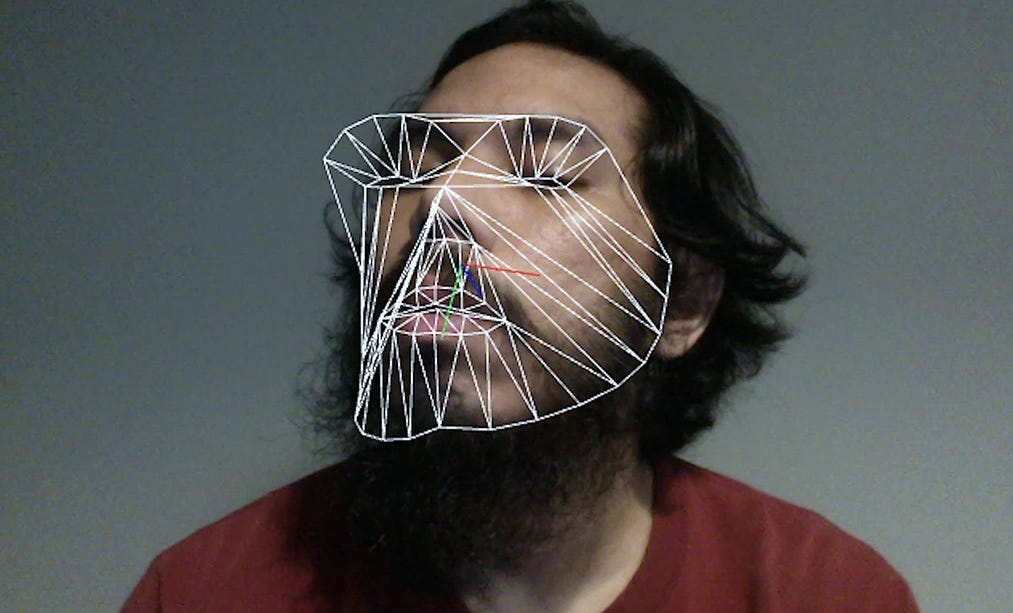

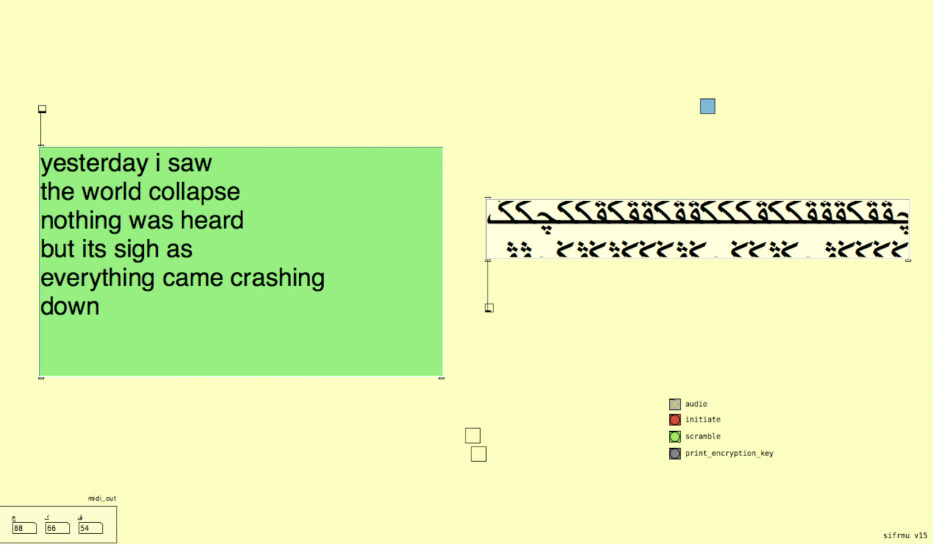

In this interview we focused on an ongoing piece, Sifrmu, developed in 2020 as a mixed media installation and instrument. Sifrmu (from ‘sifr’, Arabic & Malay for zero, suggesting also “cipher”, and ‘mu’, meaning you / yours) addresses questions of human-machine kinship and intimacy through the interface and interactions of a mechanical keyboard and software that encrypts text into the languages of Jawi and MIDI values, producing encoded poetry and sound work.

Bani: If you write something in plain text, it encrypts that plain text into ciphertext. My process at the start of it was thinking through the process of encryption: what does it mean to encrypt information, in general? Not just the process, but where else do we find encryption in our day to day life?

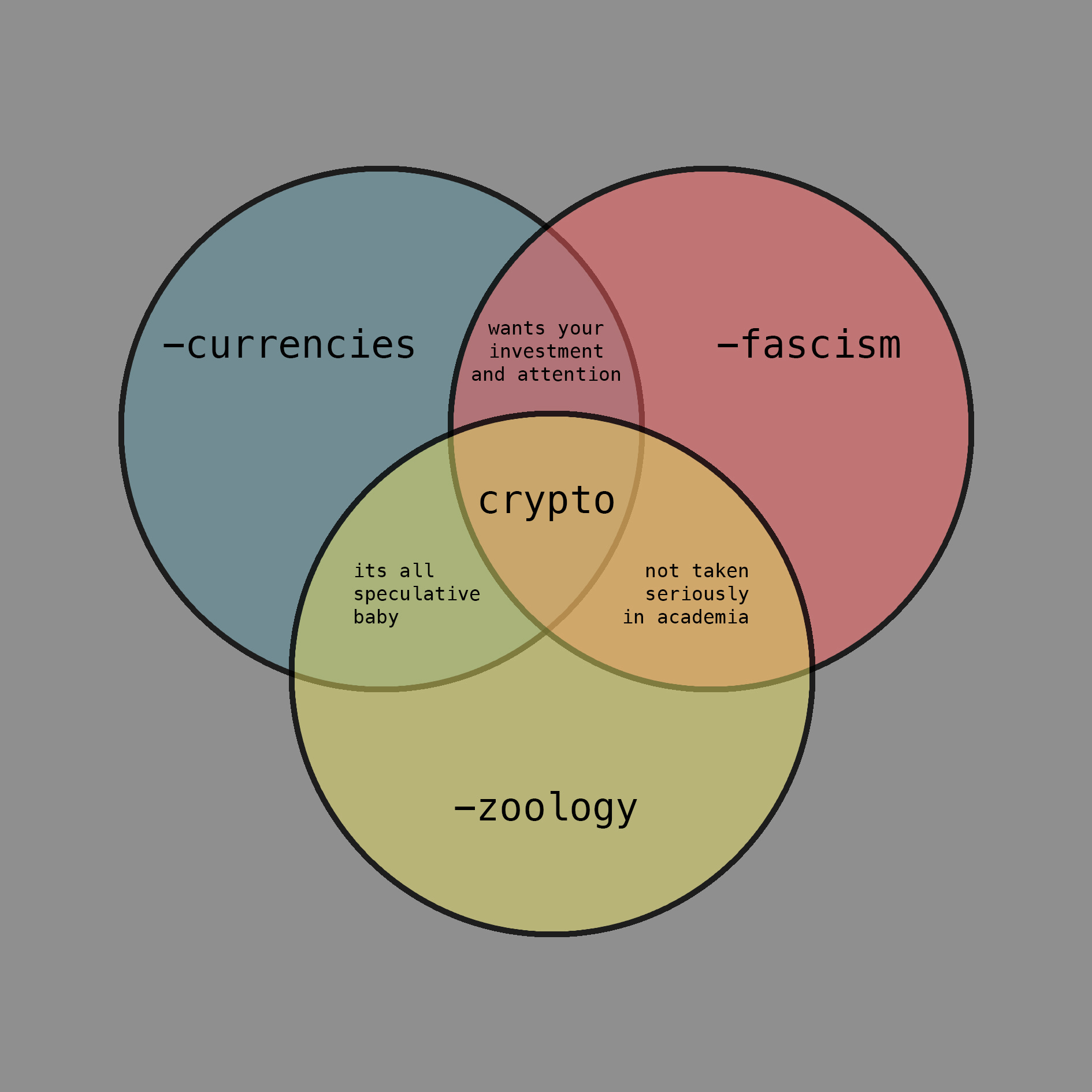

One of the first things that got me intrigued was crypto communities that dated back to the Spanish Inquisition. We had Muslims who had to practice their faith in secrecy, at the risk of being persecuted. What the crypto-Muslims did was develop their own writing form, a transliteration of Spanish using Arabic script, which was later known as Aljamiado. So you have a whole corpus of literature, books on Islamic teaching, Hadiths, for instance, Practices of the Prophet, all encrypted in a text which would not be decipherable.

The whole nature of practicing, of being who you are, had to be done in secret. That became a point for thinking about how encryption is embodied — how it manifests beyond what we know encryption to be. There’s a resonance there, because my mother tongue is Malay. One of the written forms we had before the Roman alphabet was Arabic script as well. It’s also a transliteration of the Malay language in Arabic script, Jawi. So there’s this interesting relationship shared, with very different political histories. Aljamiado and Jawi are kin; both languages adapted into Arabic script.

Eryk: Walk me through your project, how does it work?

Bani: You write plain text, which then gets encrypted. This work — on the left, plain text is written, and it’s converted through a real-time encryption process. And it generates this sonic piece. This work is an interactive work, you can write anything and the machine encrypts the information in Jawi ciphertext. There’s another layer of encryption; the sound that you hear corresponds to the letters, a visual and audio cipher. There’s an enmeshing that happens, through the digital hardware and software.

Eryk: You mentioned intimacy as a starting point of this work, how do you think about that idea?

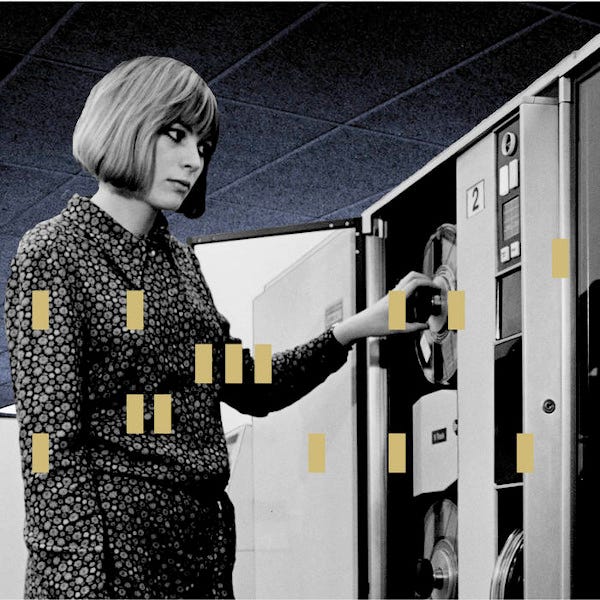

Bani: It started by obsessing over mechanical keyboards — this relationship between hands and keyboard. I think of the keyboard as an entity that is the first layer, that meets and greets all the information that eventually passes through into the computer. It’s a physical bridge. Everyone’s keyboards you would see different letters faded out, these characteristics that tell us about the uses we have for our devices. There’s still an importance in that physical presence, of how we intimate into these digital spaces. The keyboard is a mediator between all the information that passes into it and becomes data.

Eryk: There’s the keyboard too, and the musical production, but you’re producing text and information through translation...

Bani: Not translation, really. If you see on the screen, there’s an option to shuffle the algorithm around, generating a new key for each letter’s corresponding cipher. Every alphabet has its own value in the encryption process. It’s a very old encryption technique: a polybius square, which basically assigns a midi value to each letter. That generates the sound, triggering a unique sample. The combinations create these patterns, and we time the keystrokes for rhythmic values.

Eryk: What led you to structure this relationship in the way you did?

Bani: Registering the keystrokes was the important element of it — it was originally a basic sine wave synth, based on how fast you typed. An instrument that reacted to type. After that I wanted more elements of surprise for my own performances with the instrument. So the rhythmic element of typing was preserved, but as it plays new words, it changes from what it played before. It gives me a different response — and that’s fun for me.

The Sparest of Signs and Gestures

Eryk: You’ve talked about intimacy between machines and devices, I wonder how you place that intimacy in this work?

Bani: A lot of it was looking at our relationships with devices. I started with intimacy, thinking about intimacy and grasping at straws about what it means. The late Lauren Berlant writes that “to intimate is to communicate with the sparest of signs and gestures,” and that got me searching. I started to think about what this intimacy is with digital devices, platforms, applications, computers, instruments.

That’s where my interest with language steps in, because I didn’t find a resolution with the way that this intimacy is defined in English. I found it in Malay. In Malay, we have an Anglicized version of the word intimacy, intim, and it means pretty much what you understand ‘intimacy’ to mean. But a more vernacular way of talking about intimacy is mesra. Mesra can mean joyousness, that closeness that people have with one another. It can mean between friends, platonically, but also something closer and more sensual.

Mesra’s main use, though, is used in cooking. Usually you would find it as in, you’re making pancake batter. You have flour, you have salt, water, eggs, and then you mix. You mix until mesra. It speaks to a process of blending and absorption, of transformation. Intimacy, or mesra, speaks about different entities coming together to become something else. Intimacy as a process of transformation, as opposed to a description of closeness that we have with someone or something.

This framing of intimacy for me became a lot clearer in how we are becoming closer with all these devices, applications, instruments, computers, spaces, platforms... it’s not just about how close we are but how it transforms us, we transform one another and become something else. This is where this intimacy sits: not just about closeness, but transformation.

Eryk: It seems similar to the cyborg, in that the keyboard is a way of having a relationship to a machine, and the machine is changing us and we change the screen. There’s a cybernetic circuit, where we share this space, and influence one another in that shared space. But I see what you’re saying is different than a fusion taking place in there, but a blending. Less cybernetic circuit, more cybernetic pancake... looking at the pieces individually, but also as the whole that they produce.

Bani: Something I wrote about is the evolution of typing machines. It started very piano-like, tall keys and all that. Now we have wearable keyboards — no keys at all, and there’s this blending process where things become something else. I’m in this process now, with bicycles and other machines I’m close to and dependent on for urban life and functioning. My current obsession is urban planning, urban infrastructures, traffic and mobility. That intimacy we have with places as opposed to spaces. For example, our reliance on GPS — no one should use GPS. There’s a distance we have from places, how we think about sights and cities. That distancing is something I am working through this lens of intimacy. The body’s relationship with commuting spaces, for example.

Eryk: Bicycles and mechanical keyboards are these analog, mechanical technologies, what appeals to you about those?

Bani: First it’s the sonic component. Mechanical keyboards are an entire world to be immersed in. I was curious about what different configurations sounded like, what different acoustic properties felt like, the tactility of switches. As someone who started playing electroacoustic instruments, the tactility of music making has always been central. I have no virtual instruments, I don’t know how to use them, they’re very strange. I enjoy interacting with different objects.

The Intimacies of Mechanical Things

Eryk: The mechanical and the tactile are tying together a lot of ideas around intimacy and data. There’s a digital system, and you have bodies, analog systems and mechanical thinking, and then there’s the processing... and then there is the whole of it, the holistic system that emerges. How do you conceptualize the intimacy of mechanical things — or the mesra rather? And do you have a different way of seeing computers, or artificial intelligence, because of this orientation?

Bani: It’s a good question. Going back to bicycles, avoiding dependencies with GPS, for example, my question is, do I need computational processes to help me mediate the way I navigate or encounter my lived reality? How much computation do I really need? I came across a short lived movement, minimal computing — how much computational processing do we really need, how much hardware is required? That hasn’t left me. With artificial intelligence, it sits on the periphery. How much I think about it is determined by how it would make itself closer to us. How much mediation do we actually need? A lot of our encounters online are already mediated through these things.

I’m in the midst of reading Matt Tierney’s book, Dismantlings. In the first chapter he references Audrey Lorde. I found a misprint in the book and he wrote to me and I freaked out. But anyway, I really loved this part —

“Dismantling rejects the prelapsarian fantasy of a humanity that preceded machines, and it does not have much to do with the romance of a harmony between humans and machines. It is instead in search of non technological, or differently technological, human life in a world full of machines. It is also a call to examine which habits of the body or which clichés in historical narration can contribute to, and which are destined to interrupt, a culture of coalition and mutual obligation. It is an unmaking of reactionary traditions as if they were breakable machines, and a bricolage of the remaining parts into usable histories. Dismantling partakes not only of philosophical approaches to technology, but also of approaches that develop across disciplines, outside the academy, among activists, and in the formal language of literature. Lorde notes that dominant institutions and knowledge formations have been the tools of historical violence. To end that particular violence, therefore, is to break and remake institutions and knowledge formations. To do so, different tools must be applied than were designed and constructed by those institutions. And yet, it remains, you must “examine the heart of those machines you hate / before you discard them.” (Tierney 2019, 37)

This has been ringing and resonating with me through my work. A lot of it requires us to truly know, inside out, what the things are that we are being told to interact and interface with in order to refuse and discard them.

Eryk: Is hiddenness, secrecy, a part of that? Evading data surveillance, for example. If we are in the data, in the ecosystem of data, isn’t it important to be hidden?

Bani: I suppose so, but I think the element of encrypting, to hide, it’s a double-edged sword. On the one hand one hides, as the crypto Muslims did, to avoid persecution. And while there were crypto Muslims in their time, we also have to acknowledge that crypto fascists, the rise of neo-Nazis, is the result of crypto fascism. How we use these tools such as encryption methods, how and what we hide, they allow for multiple things to thrive. Encryption has been a necessity for what seeks to survive. But at the same time, what does it preserve, and what happens when it surfaces? There are still lots of these complexities to unpack.

Things I’ve Been Up to This Week

Neural Magazine, the Italian digital art & culture magazine that has been in print (yes, print!) since 1993, shared their review of “The Day Computers Became Obsolete” this month (it appeared in print in the Fall). Read the lovely review and find links to the album.

Meanwhile, Wire (UK) magazine has reviewed Worlding, also in print:

“Salvaggio’s pieces are concerned with the optimism of Worlding and the positive potential of symbiosis… the idea that they might also contain mushroom messages makes them even more compelling.”

Support the Newsletter!

Cybernetic Forests is a labor of love and will always remain open to all readers. However, if you’ve been reading for a while and found ideas or conversations useful, I’d be grateful if you’d consider a paid subscription.

To be clear, paid subscriptions are donations: you don’t get additional content. But you would help support the independent, art-driven research that goes into it.

If you’re feeling generous, you can click the link below to upgrade your subscription to a paid monthly sub. You can also support the newsletter by sharing it with a short note on your social media feed to help likeminded people find it!

Either way, thanks for reading! To upgrade, click below for options (more details beneath the button).

- Under Subscriptions, click on the paid publication you want to update.

- Navigate to the plan section and select "change".

- Choose from the following plans you'd like to switch to and select "Change plan".

Thanks! - eryk

Please share, circulate, post, or hand-inscribe it into a letter you will never deliver to your secret crush. You can also find me on Mastodon or Instagram or Twitter.