The Opposite of Information

The State of Discourse Hacking in 2023

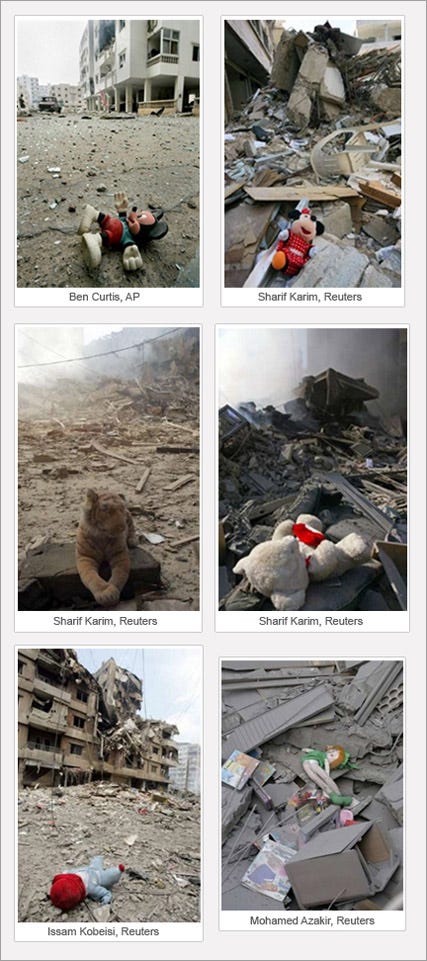

In 2006, AP photographer Ben Curtis in 2006 took a photo of a Mickey Mouse doll laying on the ground in front an apartment building that had been blown up during Israel’s war against Hezbollah in Lebanon.

Curtis was a war reporter and this image was one of nine images he transmitted that day. He’d traveled with a number of other reporters in a press pool as a way of insuring collective safety, and had limited time on the ground. He described the city as mostly empty, and the apartment building that had just been detonated as having been evacuated.

Soon after that, the photo’s success lead other photographers to start seeking out similar images of toys discarded beside exploded apartments. As more of these images started to get published, many began to ask questions as to whether these photos were being staged: had the photographers put these toys into the frames of these images?

Errol Morris talked to Curtis at length about the controversy surrounding that photo. Morris raises the point that the photo Curtis submitted didn’t say anything about victims. Nonetheless, readers could deduce, from the two symbols present in the image, that a child was killed in that building. Curtis notes that the caption describes only the known facts: it doesn’t say who the toy belonged to, doesn’t attempt to document casualties. Curtis didn’t know: the building was empty, many people had already fled the city.

Morris and Curtis walked through the details and documentation of that day, and I am confident Curtis found the doll where it was. But for the larger point of that image, no manipulation was needed. It said exactly what anyone wanted it to say.

It wasn’t the picture, it was the caption. The same image would be paired with commentary condemning Israel and editorials condemning Hezbollah. Some presented it as evidence of Israeli war crimes; others suggested it was evidence of Hezbollah’s use of human shields.

We are in the midst of a disinformation crisis. I didn’t select this example to make any kind of political point, as there are certainly people who could address that situation better than I could. I show it because 2006 marked a turning point in the history of digital manipulation. Because another Photoshopped image, found to be edited in manipulative ways, came to be circulated in major newspapers around the world.

Reuters photographer Adnan Hajj used the photoshop clone stamp tool to create and darken additional plumes of smoke. He submitted images where he copied and pasted fighter jets and added missile trails. Hajj has maintained that he was merely cleaning dust from the images. I don’t know Hajj’s motives. I can say that I have cleaned dust from images and it never introduced a fighter jet.

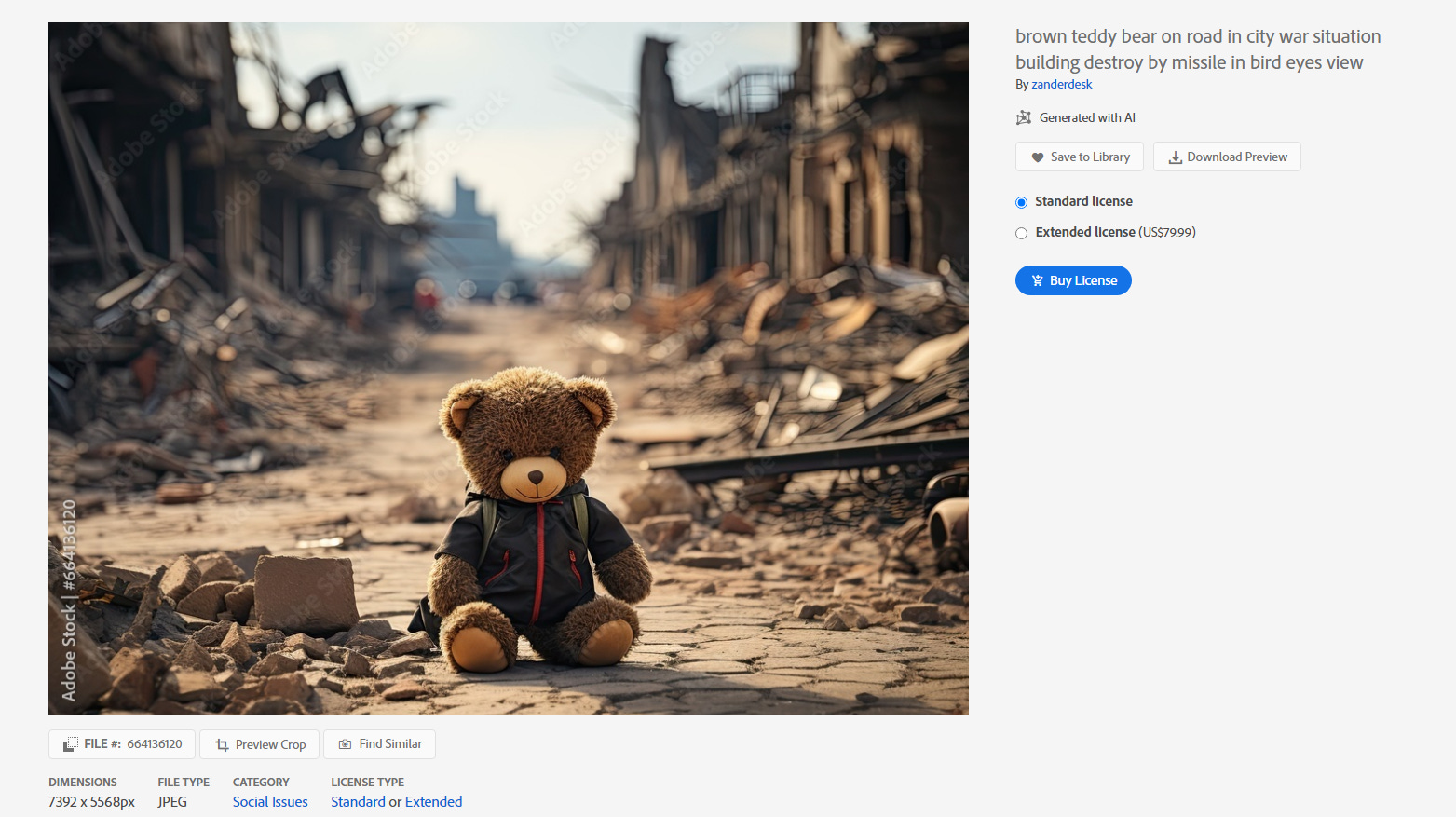

Today, similar imagery is being sold related to Gaza. This image of a teddy bear on the streets of a bombed city is presented when you search Adobe Stock photographs for pictures of Palestinians.

Adobe’s stock photo website is a marketplace where independent photographers and illustrators sell images. Adobe, which owns a generative AI tool called Firefly, has stated that AI generated images are fine to sell if creators label them correctly. This photo is labeled as “Generated with AI,” keeping in line with Adobe’s policies.

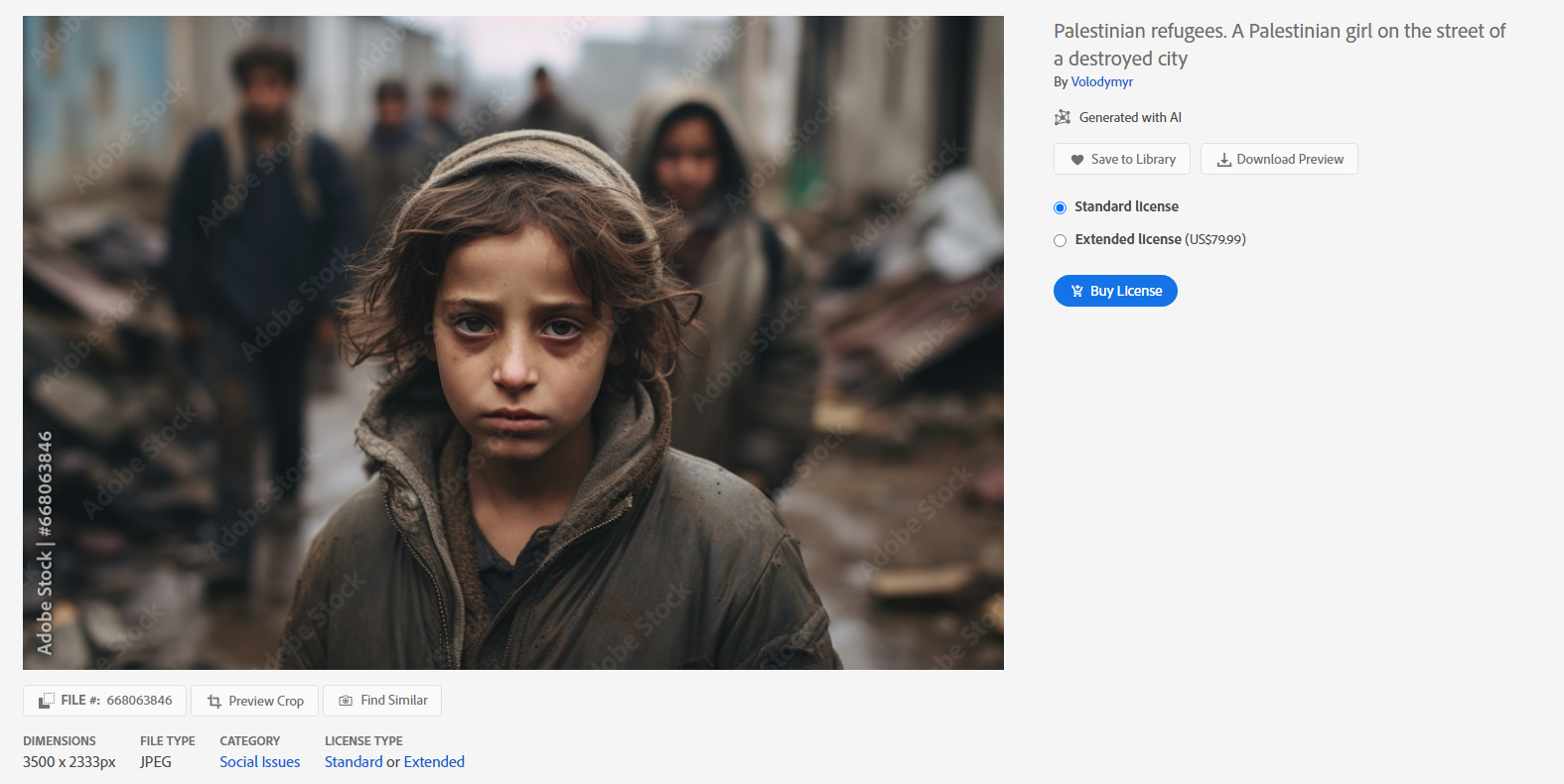

But the same photo has no restrictions on its use. Images of the bear could show up on news sites, blogs, or social media posts without any acknowledgement of its actual origins. This is already happening with many of these images. Adobe might argue that this is a computer-assisted illustration: a kind of hyperrealistic editorial cartoon. Most readers won’t see it that way. And other images would struggle to fit that definition, such as this one, which is labeled as a Palestinian refugee:

This refugee doesn’t exist. She is an amalgamation of a Western, English-language conception of refugees and of Gaza, rendered in a highly cinematic style. The always-brilliant Kelly Pendergrast put it this way on X:

Perhaps the creator of this image wanted to create compelling portraits of refugees in order to humanize the trauma of war. Or maybe they simply thought this image would sell. Perhaps they even thought to generate these images in order to muddy the waters of actual photojournalists and any horrors they might document. All of these have precedents long before AI or digital manipulation. And none of them matter. What matters is what these images do to channels of information.

They’re noise.

Noisy Channels

AI images are swept up into misinformation and disinformation. Those prefixes suggest the opposite of information, or it least, information that steers us astray. But maybe we should zoom out even further: what is information?

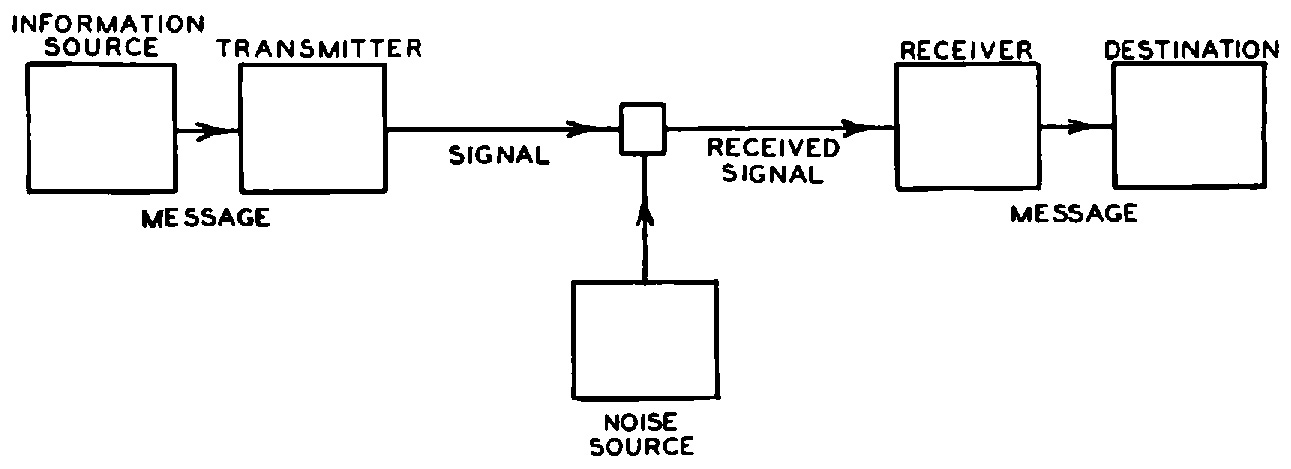

Claude Shannon was working at Bell Labs, the American telephone network where he did much of his work in the 1940s, when he sketched out a diagram of a communication system. It looked like this:

Information starts from a source. It moves from that source into a transmitter. Shannon was looking at telephones: you have something you want to say to your friend. You are the information source. You bring up a device — the telephone, an email, a passenger pigeon — and you use that device to transmit that message. Along the way this signal moves into the ether between the transmitter and the sender.

That’s when noise intervenes. Noise is the opposite of information, or the removal of information. In a message, it is the flipping of a symbol of communication in a way that distorts the original intention.

There are two sources of noise in this visualization. The first is noise from outside the system. The second is inside, when information breaks down in the transmission.

This could be a fog obscuring a flashing light meant to guide a pilot. There could be a degradation of signal, such as a glitched image occurring somewhere between the transmission from a digital camera into our hard drives. It started by understanding hiss over the telephone, but this was soon expanded to mean basically anything that interferes with the information source arriving intact to its destination.

Today, one of those things that changes the meaning of symbols is algorithms, ostensibly designed to remove noise from signal by amplifying things the receiver wants to see. In fact, they’re as much a form of interference with communication as a means of facilitating it.

Social media algorithms prioritize the wrong side of communication. They define noise as information that distracts the user from the platform. We tend to think these platforms are there to helps us share. If we don’t share, we think they are there to help us read what is shared.

None of that is the actual structure of the system. The system doesn’t show us what we sign up to see. It doesn’t share what we post to the people we want to see it.

The message in that system is advertising. Most of what we communicate on social media is considered noise which needs to be filtered out in order to facilitate the delivery of that advertising. We are the noise, and ads are the signal.

They de-prioritize content that brings people outside of the site, emphasize content that keeps us on. They amplify content that triggers engagement — be it rage or slamming the yes button — and reduce content that doesn’t excite, titillate, or move us.

It would be a mistake to treat synthetic images in isolation from their distribution channels. The famous AI photo of Donald Trump’s arrest is false information, a false depiction of a false event. The Trump images were shared with full transparency. As it moved through the network, noise was introduced: the caption was removed.

It isn’t just deepfakes that create noise in the channel. Labeling real images as deepfakes introduces noise, too. An early definition of disinformation — from Joshua Tucker & others in 2018, defined it as “the types of information that one could encounter online that could possibly lead to misperceptions about the actual state of the world.” It’s noise — and every AI generated image fits that category.

AI generated images are the opposite of information: they’re noise. The danger they pose isn’t so much what they depict. It’s that their existence has created a thin layer of noise over everything, because any image could be a fraud. To meet that goal — and it is a goal — they need the social media ecosystem to do their work.

Discourse Hacking

For about two years in San Francisco my research agenda included the rise of disinformation and misinformation: fake news. I came across the phrase “discourse hacking” out in the ether of policy discussions, but I can’t trace it back to a source. So, with apologies, here’s my attempt to define it.

Discourse Hacking is an arsenal of techniques that can be applied to disturb, or render impossible, meaningful political discourse and dialogue essential to the resolution of political disagreements. By undermining even the possibility of dialogue, you see a more alienated population, unable to resolve its conflicts through democratic means. This population is then more likely to withdraw from politics — toward apathy, or toward radicalization.

As an amplifying feedback loop, the more radicals you have, the harder politics becomes. The apathetic withdraw, the radicals drift deeper into entrenched positions, and dialogue becomes increasingly constrained. At its extreme, the feedback loop metastasizes into political violence or democratic collapse.

Fake news isn’t just lies, it’s lies in true contexts. It was real news clustered together alongside stories produced by propaganda outlets. Eventually, all reporting could be dismissed as fake news and cast it immediately into doubt. Another — (and this is perhaps where the term comes from) — was seeding fake documents into leaked archives of stolen documents, as happened with the Clinton campaign.

The intent of misinformation campaigns that were studied in 2016 was often misunderstood as a concentrated effort to move one side or another. But money flowed to right and left wing groups, and the goal was to create conflict between those groups, perhaps even violent conflict.

It was discourse hacking. Russian money and bot networks didn’t help, but it wasn’t necessary. The infrastructure of social media — “social mediation” — is oriented toward the amplification of conflict. We do it to ourselves. The algorithm is the noise, amplifying controversial and engaging content and minimizing nuance.

Expanding the Chasm

Anti-semitism and anti-Islamic online hate is framed as if there are two sides. However:

- Every individual person is a complex “side” and so there are millions

- Both Jews and Muslims are the targets of White Supremacist organizations.

The impossibility of dialogue between Gaza and Israel is not a result of technology companies. But the impossibility of dialogue between many of my friends absolutely is. Emotions are human, not technological. Our communication channels can only do so much, in the best of times, to address cycles of trauma and the politics they provoke.

Whenever we have the sensation that “there’s just no reasoning with these people,” we dehumanize them. We may find ourselves tempted to withdraw from dialogue. That withdrawal can lead to disempowerment or radicalization: either way, it’s a victory for the accelerationist politics of radical groups. Because even if they radicalize you against them, they’ve sped up the collapse. Diplomacy ends and wars begin when we convince ourselves that reasoning-with is impossible.

To be very clear, sometimes reasoning-with is impossible, and oftentimes that comes along with guns and fists or bombs. Violence comes when reason has been extinguished. For some, that’s the point — that’s the goal.

Meanwhile, clumping the goals and beliefs of everyday Israelis with Netanyahu and setting them together on “one” side, then lumping everyday Palestinians with Hamas on another, is one such radicalizing conflation. It expands the chasm in which reason and empathy for one another may still make a difference. The same kluge can be used to normalize anti-Semitism and shut down concerns for Palestinian civilians.

The goal of these efforts is not to spread lies. It’s to amplify noise. Social media is a very narrow channel: the bandwidth available to us is far too small for the burden of information we task it with carrying. Too often, we act as though the entire world should move through their wires. But the world cannot fit into these fiber optic networks. The systems reduce and compress that signal to manage. In reduction, information is lost. The world is compressed into symbols of yes or no: the possibly-maybe gets filtered, the hoping-for gets lost.

Social media is uniquely suited to produce this collapse of politics and to shave down our capacity for empathy. In minimizing the “boring” and mundane realities of our lives that bind us, in favor of the heated and exclamatory, the absurd and the frustrating, the orientations of these systems is closely aligned with the goals of discourse hacking. It’s baked in through technical means. It hardly matters if this is intentional or not — The Purpose of a System is What it Does.

Deep fakes are powerful not only because they can represent things that did not occur, but because they complicate events which almost certainly did. We don’t need to believe that a video is fake. If we decide that it is beyond the scope of determination, it can be dismissed as a shared point of reference for understanding the world and working toward a better one. It means one less thing we can agree on.

But people use images to tell the stories they want to tell, and they always have. Images — fake or real — don’t have to be believed as true in order to be believed. They simply have to suggest a truth, help us deny a truth, or allow a truth to be simplified.

Pictures do not have to be true to do this work. They only have to be useful.

(This is an extended version of a lecture on misinformation given to the Responsible AI program at ELISAVA Barcelona School of Design and Engineering on November 15, 2023.)