The Prompt

Machines will never write poems without us.

Years ago in San Francisco I had a classically painful breakup, the kind of extended, stubborn resistance to separation from both sides of the pair. Somewhere on Clement, headed toward Ocean Beach, was a Chinese grocery store where I would buy diet root beer. A sign, written in black sharpie and taped to the entrance, sunk my stomach every time:

“Please

Closing the door

But slowly.”

I don’t think much about that relationship anymore, but I think about that sign a lot.

DALLE & Disco

A handful of Artificial Intelligence models such as DALLE2 (OpenAI) and Imagen (Google) are making the rounds, competing to render photorealistic outputs from text prompts. You write a statement, the model produces an image that more or less aligns to the text, based on a statistical analysis of millions of images and captions.

The results from this generation of models seems photorealistic, though we may eventually acclimate to their weaknesses and glitches. I’ve not yet tried the model, but have worked with a few others. To compare the leap forward these new models represent, here is my own output from Disco Diffusion when it was state of the art at the start of the year. I used the prompt “a cybernetic meadow where mammals and computers live together in mutually programming harmony like pure water touching clear sky,” a line from Richard Brautigan’s All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace.

By comparison, here are some models created for me (Thanks Rodolfo Ocampo!) using the same prompt on Dalle2:

These have been rendered in a painterly style, but there are also options for photorealistic outputs. Here’s an example from Imagen (Dalle2 can do the same thing):

each example, the user is asked for a prompt. These prompts are instructions and serve a technical purpose. The models are built to link user-generated captions to the patterns of pixels found within that vast library of images. When we offer the prompt, “house made out of sushi,” the model has a series of weights it can understand as “house-ness” and “sushi-ness” and what relationships might be implied by the text (“made of”).

When we are writing a prompt, we are writing a variable for the code to execute. Much like a search term, the prompt is a technical specification, a set of instructions that influences the output. Sometimes these results can surprise us (the mushroom clouds on the screens in the second cybernetic meadow image is, well, a weird touch) but these surprises are what emerge from massive datasets, or even small systems, like the complex interdependencies of a car motor. They’re fun, useful, even thought provoking — but they are embedded in the data.

Letters to a Young Data Scientist

The prompt has space for poetry, but what it produces is the opposite of poetry. Consider the advice of Rainer Maria Rilke in Letters to a Young Poet:

It requires great, fully ripened power to produce something personal, something unique, when there are so many good and sometimes even brilliant renditions in great numbers. Beware of general themes. Cling to those that your every- day life offers you. Write about your sorrows, your wishes, your passing thoughts, your belief in anything beautiful. Describe all that with fervent, quiet, and humble sincerity. In order to express yourself, use things in your surroundings, the scenes of your dreams, and the subjects of your memory.

Rilke emphasizes the intense personal essence of poetic language. Poetry is not the language alone, but the language produced by the search for language.

The right words link an inner emotional experience to an external observation. The words are selected for their power to connect those spaces. They create a fuzzy kind of intermediate space between the interior and exterior, the personal and the generalizable. It’s personal and private, but public and shared.

If it’s possible for a grocery store sign to move us, it’s possible for a machine to move us, but neither are poetry: the emotional experience of writing a poem defines what a poem is. If there is no emotional experience — and machines have no emotional experience — then there’s no poem.

Poem Policing

Why does this matter? Having found poetry in the sign hanging on the doorway of a grocery store on Clement Street, I’m no guardian of sacred forms of language. But producing a text that resonates with an emotional experience, however that text is produced, makes us susceptible to unusual interpretations of how those words came to be seen. We often find meaning in serendipity and coincidences in ways that suggest intent: “it was meant to be,” divine intervention, a “sign” pointing us toward one particular decision or another.

When machines create these meanings, as they often do with text, this same search for intent and meaning leads us to invent attribution. Spend enough time with a text generating algorithm and you’ll find that these meanings are quite literally arbitrary. You can create new texts from the same prompts, working through them until you find one that “means.” But it means only to you, not to the machine.

When we see gaps between things we tend to create connections. I’ve covered this before in writing about image captioning software and it’s inability to understand the new context of COVID-19 in early 2020: images of people in face masks or signs about social distancing were labeled as if COVID had never happened. The world had changed faster than the database.

When you see an image and a text that has nothing to do with it, you seek connections out. You make new meanings, leap through logical gaps. This is embedded into the surrealist collage of Dadaists such as Hannah Hoch:

This image was assembled from “an advertisement for a DC-8 aircraft and the image for the red lips were cut from a photo of Marilyn Monroe,” but that’s not the image we see. But the function of creating a new meaning is being mutually discovered: Hoch makes a painting, we see the painting, we connect old images to new contexts.

On the other hand, DALLE and similar models are about the craft of the prompt. You work the text toward the model’s logic to produce the images that connect to your emotions or needs.

You have to navigate the affordances of the prompt: you learn to write for prompts in ways that the machine will understand to produce the results you prefer. In orienting yourself to a model’s language of instruction, you adapt your own.

The space of abstraction that allows people to enter into a poem, or a collage, is no longer mutually constituted. The model doesn’t have interiority, so it does not search for meaning in the ways that humans can find meaning — through emotion, sensation, experience. It has weights, and uses language to calibrate those weights.

The prompt can contain poetry as it is written — and even unintentional poetry as a result of the prompt’s demands — just as the paper taped to the front of a grocery store can contain poetry. It’s a functional poetry: the poetry of technical documentation for code work. The poetry of a prompt.

That does not mean the AI is a poet, or an artist. It’s up to us to interpret those outputs in our own contexts in order to make these outputs art. In essence, we take those images produces from the statistical analysis of millions of images and we recontextualize them into a visual culture or a poetic culture, making new associations and connections to weave machine generated words and images back into culture. The moment we do that, we create the potential space for poetry and art. But it does not come from the machine. It comes from our response.

Conceptual (vs Latent) Spaces

Poetic associations (visual or written) produced by a machine rely on poetry or images to create a simulation of poetry and images. A sign meant to stop people from slamming a flimsy door is not poetry. It serves a practical function, and that practical function is appropriated into poetry by my observation and response.

The poetic function of the grocery store sign emerged from my experience of it. The poetry came from decontextualizing the sign, associating new meanings to the same words. I did not write the poem, but by designating it as poetry, I became the poet of the sign. (Perhaps we need a new verb: to poeticize). The poetry emerged from those words as a result of an accidental alignment. There was no poet in the sense that no one wrote a poem. The poem was a result.

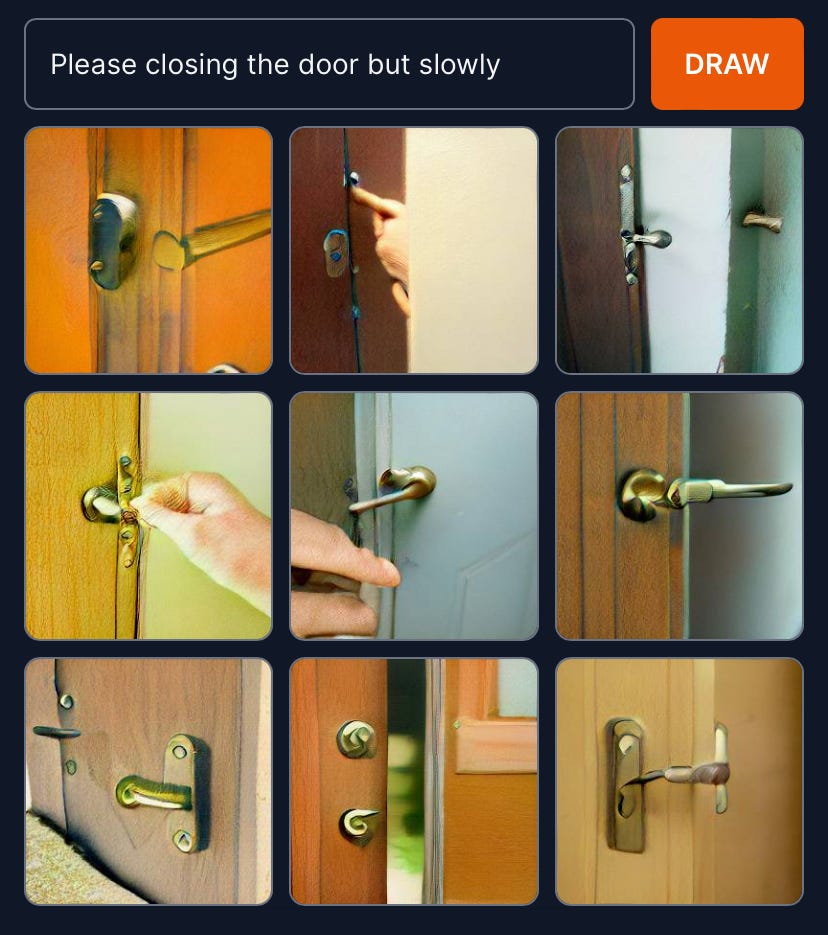

Likewise, a prompt can be a poem. There can be spaces between what is typed and what it produces. The abstractly attenuated among us may fill those gaps with associations, and the result may be poetic. For example, here are nine outputs using the grocery store sign as a prompt for a publicly accessible DALLE replica:

Perhaps I am poetically inclined, but there is something poetic at work here. I suspect the poetic impulse is distance. There is a sweetness is the space between language and meaning. Language declares a thing “to be,” and names it. To name is to constrain: to be a thing, in reference to other things of similar quality, reduces the distinctiveness of a thing from what it is and what language describes it as. The images show me nine doors that do not exist, but share a state of being, of opening slowly. The nine doors are not the door where the sign was hung.

There is something to be savored in that gap. It reveals the distance between my experience of the thing, the words that described that experience, and the way those words are interpreted. My experience of the poem was already abstract, now it becomes abstracted further. It becomes expressible through images, accessible in new ways. Entangled with my experience of the phrase and the prompt, the images take on a patina of poetic resonance through the accident of juxtaposition.

This does not mean the machine “wrote poetry.” The machine produced images which were contextualized as poetry. The person reading the results may, or may not, produce this poetry. There are a million images of half open doors in the world; people beyond the scope of this essay or conversation may never see them as poetic. I look at a gap in meaning and I close it. I draw a circle of abstraction and a picture of a slowly closing door can be pulled into the circle. Videos of scenes from films and home movies where doors are closed slowly may be put on loops and installed into a museum, if I were ever so inclined to build a museum for a failed relationship. (I am not).

This is the weird, abstract, emotional experience of language and the world. Poetry is the struggle of looking for the words that say the thing you need said, in the way you need them said, and the deep relief that comes in finding those words. Images can do the same thing; some artists find these “words” only through lines or pixels. Musicians find them in timbres and tones.

That mental conjuring, tied to the experience of our bodies, is key. The machine cannot write poetry or music. But now that we have models which take language and render words into visualizations, the prompt becomes a site of poetic possibility.

The Prompt as Form

There are constraints to the interpretation. DALLE and Imagen ask us to search for words that produce images. But we have to navigate the needs of the system, rather than the needs of our own expression.

The same happens with a sonnet, or a haiku, or any other poetic structure. The poet faces constraints of form whenever they choose form. Syllable counts, rhyme schemes.

Language itself is a constraint. Why is it even plausible that the word that expresses your emotional experience is in the English language? Perhaps it is in German. Perhaps Japanese. Perhaps it is a primal wail, the screaming gibberish of babies, that weird yodel in Vampire Weekend’s “Ya Hey.”

The structure of our expression could be much more than language. If we want to blame the constraint or affordances of the prompt for forcing us to conform to its logic, we would have to ask why we speak with our mouths. Art suggests other entry points into the space of shared experience.

The poet can craft a prompt according to form, and the results that emerge may respond to the prompt. We might be tempted to say that the machine produced art, but it did not. The machine is a tool, designed to take your prompt and calibrate a range of pixels based on the probability that they fit the categories of things the prompt includes. Mention a door, and it will find the most door-like constellations of pixels. It finds them by having exposure to millions of images, hundreds of thousands of which will contain doors, expanding the models access to a category of door-ness.

When you submit a prompt, the model is an intermediary between yourself and those millions of images — a conduit for the millions of artists who made those images. They make collaboration possible by eradicating collaboration. They present an image based on the images of a million others. Those millions were not compensated nor asked to collaborate with you.

The prompt provokes possibilities, but it isn’t imagination. It is statistics, categories, and references. But statistics, categories, and references may themselves be art! The key is that they will always require a human to assign them as such. We create conceptual boundaries and decide what to bring in and what to leave out. Widen the circle too far and you quickly lose context and meaning. Too narrow, and you lose the scope of possibility that creates new ways of understanding.

It’s not only about observation — this is not a koan about an AI producing images of a tree falling in a woods with no one to save the output (does it still make a sound?). This is about the conscious role of designation in works of art: the declaration “this is art” requires a human to make it. To make an object, a text, an image a work of art is to make it a work of art. Behind every found object in a gallery is a human being arguing for its inclusion into art’s conceptual sphere, drawing on experience and reason, gut feeling and intuition, that machines cannot produce.

Will an AI ever produce art on its own? I don’t think so. But it can produce found objects, and humans will certainly find them.

Things I’m Up to This Week

I’m excited to be included in the new book, Frankenstein Reanimated: Creation and Technology in the 21st Century out on Torque Editions Press. Edited by Marc Garrett & Yiannis Colakides, the book connects and expands on three international art exhibitions at Furtherfield (UK), NeMe (Cyprus) and LABoral (Spain). Each explored the resonance of the techno-social themes within Mary Shelley’s original Frankenstein.

It features work and interviews with many excellent artists who are engaged in technology and art, including Alexia Achilleos, Zach Blas, Frances A. Chiu, Ami Clarke, Régine Debatty, Mary Flanagan, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Srecko Horvat, Salvatore Iaconesi, Olga Kopenkina, Marinos Koutsomichalis, Shu Lea Cheang, Gretta Louw, Joana Moll, Laura Netz, Eryk Salvaggio (that’s me!), Devon Schiller, Guido Segni, Gregory Sholette, Karolina Sobecka, Alan Sondheim, Michael Szpakowski, Eugenio Tisselli, Ruben Verwaal, Paul Vanouse.

Here are some nice comments:

“This collection shines a light on artists as critically engaged citizens providing a kaleidoscopic view on our unevenly distributed future. These are the Frankensteins we need!” — Felix Stalder, Zurich University of the Arts

“Frankenstein Reanimated is an important record of some incredible artists working today, who both dismantle and rebuild our contemporary technological systems, profoundly reimagining everything from facial recognition to AI, 3D printing to virtual gaming environments.” — Sarah Cook, University of Glasgow

Order the book on Motto or Amazon.

Thanks for reading this week! As always, feel free to share if you feel so inspired, or subscribe if you’ve found it shared with you.