The Zambia National Academy of Science, Space Research and Philosophy

When you laugh at the Other, the Other laughs back into you.

“In the 1960s, while we’re going to the moon, you didn’t need special programs to get people interested in science and engineering. It was writ large in the daily headlines because every mission was more ambitious than the previous mission. This went higher, this orbited longer, now we’re docking, now we’re going to launch the craft that’s going to the moon, now we go to the moon. And you knew it was fluency in science and technology that was empowering that journey.”

— Neil deGrasse Tyson in The New York Times Magazine this week.

This quote has been occupying some space in my head since I read it. Tyson is advocating for “big” projects, like the moon landing, as a way of generating a new era of excitement about technology and engineering. I think this is all fine and good, for a nation like America, which has spent enough money on a seemingly endless stream of much less inspiring things. But America’s triumph on the moon wasn’t just a science communication exercise.

The Cold War was not just a military rivalry between superpowers. It was also an ideological one that pit communism against capitalism. The United States and the Soviet Union both sought to extend their influence across the world, deploying cultural propaganda and military force to attempt to bring countries such as India, Ghana, Cuba and Nicaragua into their sphere of control. “Nonaligned” countries, especially the many African and Asian nations that fought for independence from imperial powers after World War II, became sites for proxy wars. The cosmos was no exception. Space represented the ultimate nonaligned sphere — a new territory for the planting of flags, ripe for colonization.

The race to space from Zambia — a “non-aligned” nation — looked a bit different. Most of the existing English-language footage we have of the Zambia National Academy of Science, Space Research and Philosophy is infused by the colonial mentality that the nation was floundering in its independence from the British: a BBC reporter, watching these teenage Afronauts as they jumped from swings to feel gravitational forces, called them “crackpots.”

That all fit into a helpful narrative for a collapsing British Empire, and an American Empire that saw space programs as a recruitment tool for non-aligned nations. But that narrative obscured what was possibly another, more compelling force.

The Zambian Space Program was created by Edward Makusa Nkoloso. Details are murky, but it seems Nkoloso was a high school science teacher who founded a school only to see it shut down by the British. When he defied their orders and ran it anyway, he was arrested and served a year in prison. (In UK media reports, he is identified as a “disgraced high school teacher.”) Nkoloso joined the resistance movement before the country gained independence as a fighter and an organizer.

The space program — which was not funded by the Zambian government — reads differently when you place it into a context of anti-colonial sentiment, as opposed to storytelling framed by the country’s former occupiers. Nkoloso wasn’t some clueless scientist: he was a high school science teacher described as “well-read” even by his rivals. He was a political activist who spoke Latin, English, and French. And he was all too aware of the relationship between colonialism and two great powers in a race to claim new territory on the moon.

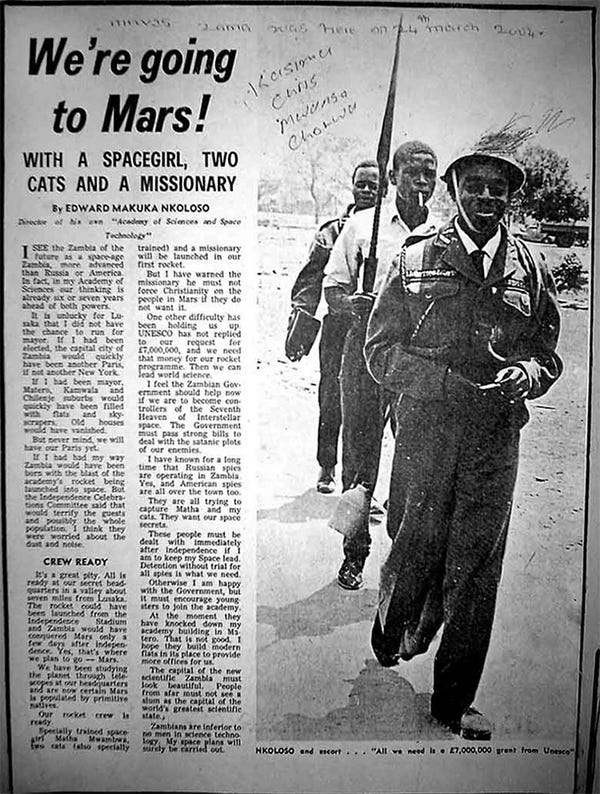

His op-ed announcing the program to go to Mars, published in a Zambian newspaper, drew international mockery. Under British Colonial Rule, Zambia had 1,500 African high school graduates among its 3 million citizens, and about 100 African college graduates.

The ridicule missed the point of the exercise. This was two years before any object from Earth had landed on the moon. I can only read this announcement as that of a former subject of the Empire extending a giant middle finger back in its direction:

“We have been studying Mars from our telescopes at our headquarters and are now certain Mars is populated by primitive natives. Our rocket crew is ready. Specially trained spacegirl Mata Mwambwa, two cats (also specially trained) and a missionary will be launched in our first rocket. But I have warned the missionary he must not force Christianity to the people if they do not want it.

Mata Mwambwa was a 17-year-old girl, and I can’t find the ages of the other students in the academy. Some report that this was not an organized program, but a “publicity stunt,” often tied to Nkoloso’s request for $7,000,000 in space funding from the UN, which bolsters claims that he was also, perhaps, running a con. I doubt it. I presume Nkoloso knew there was no way he would get $7 million, or the additional billions he would request over the years from the US and USSR alike. It seemed to me another satirical jab at how science was funded among non-aligned nations.

If it was a publicity stunt, I want to think the “publicity” was a conversation about the role of science, and science funding, in a newly formed nation. No different from what deGrasse Tyson described above. That same article also had these lines:

The capital of the new scientific Zambia must look beautiful. People from afar must not see a slum as the capital of the world's greatest scientific state. Zambians are inferior to no men in science technology.

Arthur Hoppe, a San Francisco Chronicle columnist, went to cover the program in the 1960s. He reported home that the whole thing was a very complicated dry joke. He pointed out that as the United States was spending nearly $20 billion to go to the moon for the sake of national prestige, many Zambians he spoke with thought Americans “were out of their minds.”

A joke, but a complicated one. The program is also a gesture toward cultivating the imagination that fuels science and technology, the ones that deGrasse Tyson mentioned. It isn’t so wild to imagine a high school science teacher with an activist angle taking high school kids to a science summer camp with the pretense of going to Mars. Everyone involved, let’s remember, is smart enough to get the joke. We don’t have to tell high school kids at Disney World that Space Mountain isn’t really space (or a mountain).

With that in mind, have a look at this deeply colonialist take on the program, and ask yourself who the real fool is: Nkoloso, or the BBC reporter who looks at a concrete rocket ship and continues to ask Very Serious Questions.

(Content Warning: this whole clip is one giant racist heap, and the “modern” snippet of commentary at the end isn’t any better. I’m hoping I’ve contextualized it enough to reverse the mockery.)

Nkoloso is absolutely trolling the British because he can.

That reporter’s laughing-at, not-with persists today: Google the program and you’ll find it listed as a spectacular failure, “hilarious” for reasons dripping with colonial racist assumptions, proliferating a myth of hapless former subjects of Empire become once left to govern themselves.

Activating the imagination of youth in a newly independent nation through a kind of winking whimsy seems to be a more straightforward take, and it requires quite a bit of contrivance or bad faith to miss that interpretation. The Zambian Space Program spoke to an imagination that colonial powers were keen to misunderstand because it was not a formulation of a colonized imagination.

Of course, it isn’t mine, either, and I would hate to “prescribe” an interpretation. I just believe there is ample room for more generous ones.

I am conflicted, for example, by the images from the London-based photographer Cristina de Middel’s Afronauts series, which “recreated” the space program through re-enactments for a photo series in 2011. The images are beautiful, but de Middel speaks somewhat patronizingly in interviews to some of the same clichés reported by the BBC in 1965, including the “innocence and naivete” of Nkoloso’s endeavors. I don’t buy it.

Another take, from 2019, comes from Nuotama Bodomo’s short film Afronauts (you can watch in its entirety below). Bodomo looked to the Zambian Space Program as an early gesture of Afrofuturism. The film re-enacts actual training regimes from the program but imagines it all somewhat differently.

Zambia did not get to Mars. The mission was still a success.

FYI: I am not the first to read the program this way — The New Yorker published an excellent article on this in 2017.

Things I’m Doing This Week

Last month I was invited to the OpenAI GPT-3 beta, a tool for generating text which aims to be indistinguishable from human writing. I’ve been playing with running the GPT-3 output through text-to-speech processors, then pairing them with AI-generated piano scores to generate “spoken word” ambient pieces. The result is alien, eerie, and kind of beautiful, but I am the one putting them together.

See what you think! This one was prompted by a talk I attended last week with Taeyoon Choi and Alex Galloway discussing textiles and networks. But, as happens with these systems, there’s no real connection to the prompt.

Things I’m Reading This Week

###

African Influences in Cybernetics

Ron Eglash

An article that reads like a timeline of intersections between Africa and cybernetics. I’ve just discovered Eglash through a web conference on African AI & Art. In this article from 1995, Eglash looks at the African origins of cybernetic tropes — such as the systems diagram:

We see animist energy flow, drawn by a Bambara seer for the author, visualized as a sort wave emanating from a sacrificial egg. The dashed lines inside the figure are a digital code symbolizing good fortune. Undulatory schemes in Egyptian art (Badawy 1959) show an understanding of motion as a rhythmic time series, and the transformation of time-series to a frequency-domain representation can be seen in African conceptualizations of circular time. The extreme in African time-series analysis is the search for patterns in the Nile floods. The most recent data set, taken once a year for 15 centuries, became the basis for the work of H.E. Hunt mentioned previously. A British civil servant, Hurst spent 62 years in Egypt, and finally deduced a scaling law, based on this time-series, which Mandelbrot used to bring Cantor's abstract set theory into empirical practice.

###

Appropriate Measures

Jackie Brown and Philippe Mesly

A compelling critique of the idea of “appropriate technologies” — the idea that we can mitigate environmental harms through small, locally focused, democratically designed technological interventions. This misses the point, the authors write, that productivity is not the goal: expanding well-being is. They write:

Technological practice cannot, by definition, be construed in any other way than as productive (though its rate of throughput can vary widely), and it certainly does not lend itself to “letting things be,” which he views as a foundational component of any degrowth strategy. In other words, when social change is framed primarily in terms of choice of technology, the debate necessarily centers the activity level of a productivist society, not a paradigm shift from growth to wellbeing.

###

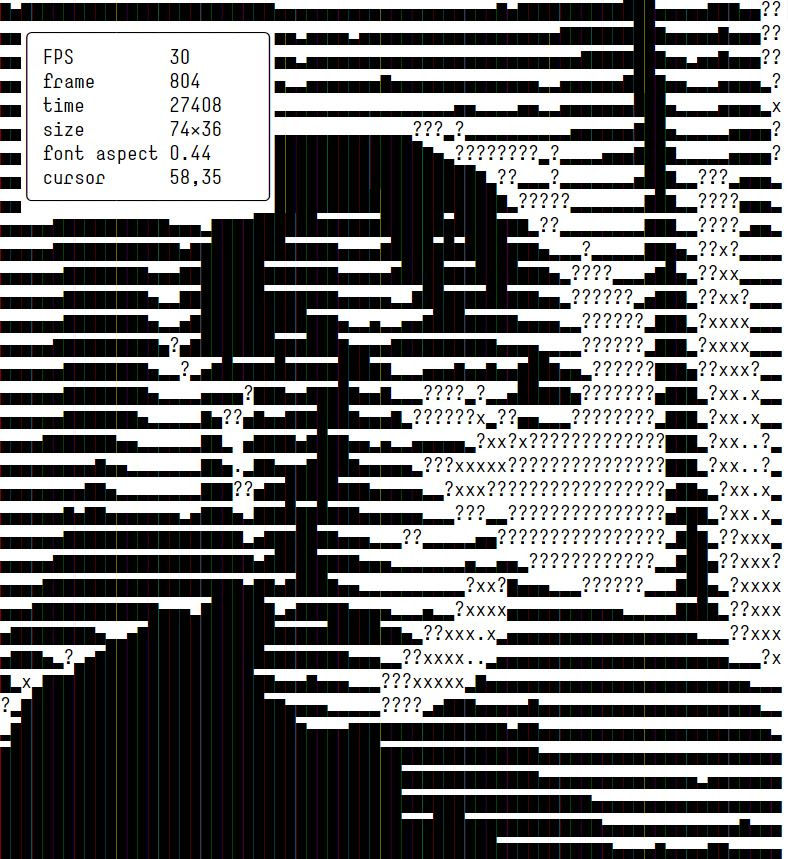

Impossible Images and the Latent Image Space

Rosa Menkman

Menkman’s talk at MIT builds on her work cataloguing “glitches” in images, and begins to describe how glitches are used in popular culture as a kind of vocabulary. For example, she found that static often suggests supernatural events whereas sudden bursts of digital noise suggest alien interference. The entire video also happens to be a rich visual experience.

The Kicker

Go make some ASCII code-art animations, like taking an ASCII selfie, in this really fun no-coding-required code playground.

Thanks again for reading! If you dig it, please share, circulate, and tell your friends to sign up. If you got a link to this page, feel free to subscribe for weekly e-mails just like it.