The Zero Has Traces of the One

A Conversation with Michèle Saint-Michel

Michèle Saint-Michel (web) is an intermedia artist, filmmaker and author. Her genre-bending works encourage healthy coping and recovery from difficult experiences. She describes her films, books, and sound works as a way to “cross physical intimacies and conceptual distances — power to surrender, joy to trauma, nature to technology, and analog to digital, creating a conditional and reactive multi-temporal space where new futures can be imagined.” She's the author of three books, Grief is an Origami Swan (2020), Saint Agatha Mother Redeemer (2021), and Liner Notes for Getting Out Without Catching Fire (2023).

Michèle and I connected a while before collaborating on a musical companion piece to her latest collection of poems, Liner Notes from Getting Out Without Catching Fire. The album, Getting Out Without Catching Fire, collects musical responses to poems and themes in the book. It features a diverse roster of artists, including Sheena Dham, Hermon Mehari, Lina Dannov, Arun Sood, Sylvia Hinz, James Fella, Silvia Cignoli, myself, and three tracks contributed by Sophie Stone.

This interview covers a range of topics, from the tensions of technology as poetic metaphor to links between trauma, grief, and artmaking — and whether or not generative AI is a remix, or something else.

We talked ahead of the book and album launch on August 3 — and if you’re interested in attending a listening party, you can find details here.

The Department of Defense is a Metaphor

Michèle Saint-Michel: Over the last year, my work has explored the sympathetic nervous system and trauma responses like flight or fight, and the lesser understood fawn and freeze.

I’m touching on heavily emotional topics like grief and mourning, trauma, gender-based violence, and violence in the home. All those words will bring up flags on any kind of social media page, so I like to talk around them if I can. I like to go for the head fake in all my work. It's important to me and my survivorship to talk about these heavy subjects, so having a creative approach allows a lighter touch and more nuance.

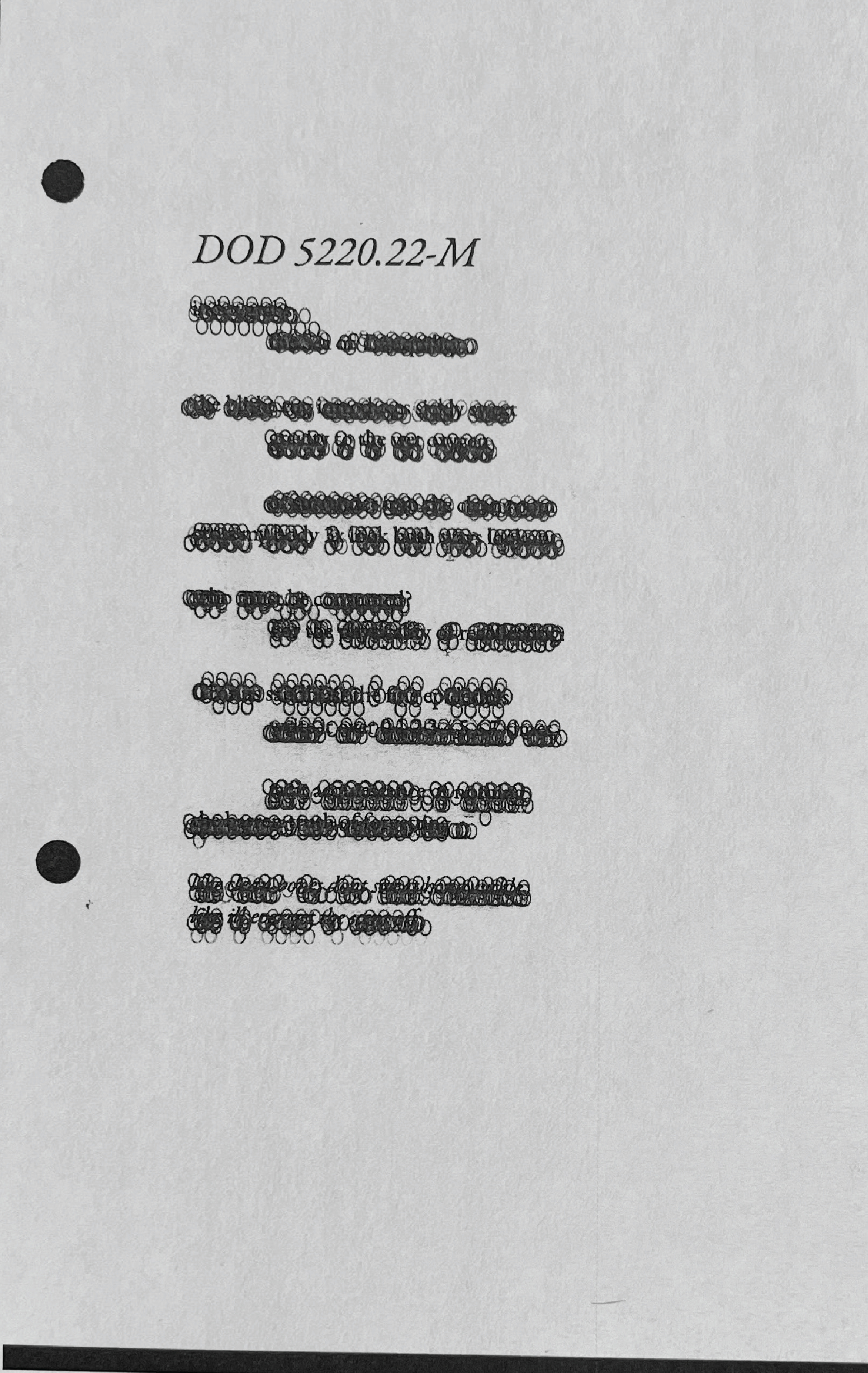

Eryk Salvaggio: You explore a lot of technological processes in your work, as kind of an additional layer of your poems. Maybe we can start there, with the point where our collaboration started, a poem called DOD 5220.22-M.

MSM: The title comes from a Department of Defense protocol for erasing documents. It’s a multi-pass method that overwrites data with a series of zeros, ones, and random characters to ensure that the original data cannot be recovered. I've presented the work as erasures, so you can't see it. It is all blocked out with zeros. In this case, I've gone over it seven times with an analog typewriter. But on the backside in the book, you can see the text carried through. I love to play with this digital interpretation of the analog and subvert this ease and speed that we come to associate with technology, to make it meaningless by digitizing analog. In this case, I'm typesetting this in a software, I'm printing it out, I'm getting a physical typewriter and I'm typing over it. I'm then scanning it and digitizing it again.

ES: Your work is invested in process, and the work that we see is always deeply informed by the steps you’ve taken to make them. How does the process inform the meaning here?

MSM: It's about trauma and it's about memory. A lot of times when you're thinking of trauma and experience, if you go to therapy, they'll talk about this idea of hardware and software. When you have a traumatic experience, how the brain functions can best be described as wetware, in which what is happening and where it is happening are completely intertwined. Trauma gets locked into what they might call your reptilian brain. You can't access it directly and often those traumatic experiences are, or become, unknown to you.

So I wanted to create a work that was there but wasn't there. Just like a lot of traumatic experiences are locked away, but they'll be with us all the time. They take up space, but on this inaccessible plane.

The front side of that piece has been all typeset with zeros. It's the erasure going over it seven times, referencing Department of Defense protocol. I’m taking that and making it a personal practice. But on the back of the page, I've reversed the typeset so you can see what would be there, bleeding through the page on the opposite side. It’s an analog version of this deeply digital process that I've used. It took ages to align everything in the physical book. It is really rich in contradictions, and I love exploring that in the work.

ES: In a digital medium, the zero would be erasure — the absence of information — in the sense that there would be nothing there. But by printing it, you're actually building up this density of zeros, a density of nothing over time. These layers of absence are actually a presence, which I thought was really moving.

MSM: And you brought that into your response.

ES: Yeah, as I was trying to articulate a response to the work, I also engaged in the quantum themes in your poems, particularly superposition. If there’s a zero in the space where a zero is being written, it stays a zero. Only the ones are erased. In the audio piece, it’s generative audio — two tracks, left and right, which start with the same random number sequence but evolve in two different directions. On the left is one set of possibilities for that number sequence, on the right is another. But the track on the right has information slowly removed, becoming distorted. So there are two parallel paths coexisting for that initial sequence, but one is being erased and one is uninterrupted. The listener connects both of them: the presences and absences play off of each other, forming an audio representation of that entanglement between information and its absence. Then, finally, the tracks do reconnect. The distortion stops. But the pieces are radically divergent.

I was interpreting your original work in terms of mourning. With mourning, there is a split. There were two possibilities: something continues or something ends. But time can be complicated with mourning and acknowledging loss.

MSM: There's this great book from a neurologist about grief. She talks about how, after someone dies, your brain literally takes weeks to rewire. It's expecting that person to walk through the door. There's a physical process that your brain goes through to unlearn that, or learn over that. You literally are still expecting to experience this person who has passed away in their life, because your brain doesn't know any better. It hasn't figured that out yet, even though you know they are gone. The circuitry hasn't figured it out.

Traces of One Within a Zero

MSM: Liner Notes for Getting Out Without Catching Fire is straddling this idea of leaving and not leaving. When we think of leaving a bad job or relationship, the default is that you're wanting to go. And we often champion people who leave. We call them brave but this is based on the presumption that there is a choice — I think that’s a false dichotomy. Many times what’s happening is we are being forced to accept the least-worst option. So maybe we can't leave this job because we need the money to go to school, or to put our kids through school. And maybe we can't leave this relationship because it's not safe to do so, and we'd be putting ourselves in even more danger if we left.

That’s at the heart of every piece in this collection. I think it's the thread that holds the collection together. The collection also lifts up feminine relationships in all their iterations: sisterhood, mother-daughter, aunties, friendships, sorority, and all the myriad relationships between and among women.

It's also heavy on quantum physics and superposition. So this comes back to what you were saying, about this idea of two things crossing themselves out. That is a theme that comes up again and again in the book. One minus one isn't the same as always having zero. Like, one minus one equals zero. But it's not the same as never having something. Because having something and then losing it is a different psychological weight, a principle of loss aversion

One minus one equals zero. But it's not the same as never having something.

ES: Right! You have traces of the one.

MSM: Yeah! And the book, it’s about music, of course, and art. Most of the titles are plucked from artworks or other songs. And there's lots of music and color field paintings throughout the book in the language, even though the book is black and white. The language is incredibly colorful and it's taking you on this color story of a bruise healing: we start with purples, and we go through, yellows and blues and ending in reds and oranges and kind of that soft pink.

Xerox: Set The Page Free

ES: Tell me about the Xerox machine.

MSM: This Xerox machine idea has been the bane of my existence. We were clear in saying that this book was made on a copy machine. Some of the pages are unreadable. For example, in the poem we were just talking about, that poem has all these zeros. But we can’t distribute it! We just received an email, actually, right before this. They are saying that I'm violating their terms and that they will not distribute this book because I made it on this Xerox machine.

ES: Ah, yeah, algorithmic flagging in the physical world. To be clear, too, this is an artistic decision, to use this machine, right? There’s thought behind it!

MSM: Absolutely. I made it on the Xerox machine because it's referencing The Real Book. Which, for people who don't know, The Real Book is a collection of jazz standards. It's really expensive to buy all the sheet music, but to be a real jazz musician they say you have to “spill four cups of coffee” on the sheet music in this collection, go through the whole thing and know it back to front. So musicians just go into Kinkos and make copies. They distribute them as bootleg versions and they call it The Real Book of Jazz Standards or whatever. I love that.

This book references so much music and jazz. Some of the poems are set in Kansas City, and I was born in Kansas City, so I wanted to have that as a visual backbone of the book. It's really causing me a lot of grief. But I don't care. It looks amazing.

ES: It's technology raising a flag again, where the motivation for your work is kind of secondary to whether it looks like something that violates an arbitrary term of service.

MSM: No, it is. I hate it. I think that AI has come in and they have some kind of scanning process, where before it was just a person who could see the context. I have tripped the trigger somehow. I'm very grumpy about it. They've said, this is our decision and it's final and we won't respond to this any longer. It's a hostile vibe.

Everything is a Remix (But Not Like That)

ES: So The Real Book served as inspiration for this book of poems, which has served as the inspiration for this collection of sonic experiments, which is where we ended up collaborating. Where did that decision come from?

MSM: All of these poems are directly referencing art or music or sometimes other poems. From the beginning, I knew I wanted to have the option of remixing ideas for the collection. That's why it's called Liner Notes, because I wanted to have the actual album be Getting Out Without Catching Fire. The poetry collection would be the liner notes for this album.

ES: Which couldn’t exist until you wrote the liner notes.

MSM: Yes, but also the album has always been there. It's difficult to find enough musicians and find people who have the time and inclination to work on these poems, that have challenging subject matter — I knew it would be a hurdle. But it has been there from the beginning. I'm obsessed with music, especially experimental music and jazz. I think it brings something to the work that I couldn't bring alone.

ES: How has that process been?

MSM: By calling the poem and the song, for example, “The Death of Cleopatra”, I’m creating a multi-meaning. If you were to search for the phrase, you will have the event, the artworks, the Edmonda Lewis sculpture, and now Hermon Mehari’s song, and my poem. They are now in conversation. So it's a remix of the remix. It's exciting, and it made a lot of sense in this particular case when quantum superposition is already in play.

ES: So I am constantly thinking about issues of generative AI. But I don't want to drag you into that conversation unless you want to be —

MSM: Do it!

ES: OK! So, I think superposition, as a metaphor only, can be a lens to look at generative AI. A generated image exists as this fragment of in-betweenness, it’s a particular state before you move to a new possibility in almost any direction. Is that a kind of superposition?

MSM: Maybe because I am a filmmaker, I think of it a little bit more visually, where superposition is like one thing happening on top of the other.

ES: Yeah, OK. Or not even on top, but in simultaneous space, in a way.

MSM: Right. And then it leads into something happening and not happening at the same time. I was trying to make Superpositionism a thing for a while. I was mostly using it in my film collection called The PTSD Suite, where each of the works addresses a different symptom of PTSD. They're meant to be shown in any order and in any combination, which doesn't work for most screening situations. It's for a theater that doesn't exist yet. I'm using archival footage and footage from my personal archive and new footage. I was trying to create three places at once — kind of how it works when you're having a flashback. You're in your current state, but you're having this other experience in your mind. I always think of superposition and trauma. But you're using it in reference to grief.

ES: I risk trivializing grief or trauma in a way, but that experience of superposition and the remix and generative AI is, I think, still important, specifically because that range of possibilities is so personal. If we look through the lens of remix culture, then all these possible versions of a thing are dormant inside the thing itself. An object, a song, a painting exists in itself. But simultaneously, so do an enormous number of possible alternatives. This has always been the case, but the AI lens is perhaps mainstreaming that view of the world.

But let’s talk about the remix first. You just described taking a sculpture, turning it into a poem, and having that become a piece of music. That form of remix seems to insist that something unique survives even when it’s obscured, which I think ties into a lot of the work that you're talking about. In connecting process to a metaphor, there’s something really hopeful and optimistic about that, something that gets lost when we automate it.

MSM: When I am talking about superposition, I'm thinking of one thing being in several states at once, and this is because when I'm talking about that, I am pointing at trauma. Or grief or this emotional overlay that we're having. I think it is a really nice metaphor, and maybe not even a metaphor. Maybe it’s a good descriptor of what is going on with us at all times. We can feel grief and joy, right. And it doesn't mean because we're feeling joy that we're not also grieving, but that looks different from the outside, but it feels understandable from the inside.

We understand it intuitively. And of course, all of these things you described — just calling something a remix — is conveniently forgetting all of the real work that happens in all of these things. “Everything's a remix,” is hiding all the real work and human connection and interaction that had to happen. For example, in our collaboration, right? All the emails and all the back and forth and all of the oh, this didn't work out, and oh, this is going to be the one. And is it this version or this other version? That was a lot of work that no one will ever see.

ES: It’s attention.

MSM: Yes, attention! I don't know how you represent that. You can't. I'm not sure why it's interesting to hide that, actually, but it feels like it's a meta-interpretation of reality, right? Of this superposition. We are operating in these different ways and all you see is this external person laughing, but you don't know that they're having these other experiences at the same time.

I like this idea that you're saying that there was a point where it didn't exist and now suddenly, because of generative AI, it is now existing. The remix has existed, it's just meant a different thing, but we don't have a different word for it. When I think of remix, what I'm thinking is: here's this thing, and it was either so good or it was missed somehow. I want you to give it more attention. It's an offering.

I did this with my second book, actually. Saint Agatha Mother Redeemer is a really dense, small, experimental, concrete poetry collection and it's meant to be difficult to open. It's so thick and small. But I wanted a more joyful, lighthearted opening into the work. So I made it into a coloring book; this huge 8.5x11, black and white, big font, so people could give it more attention if this other way wasn't it. If the first one doesn’t work for everyone, then let's offer up this remix and let's get more attention to it.

It is attention, and I guess that's what they say: it's the attention economy.

ES: Maybe there’s an inattention economy. What can we not pay attention to? How do we hide and obscure that labor? From workers cleaning data to artists making conscious efforts to reshape material in meaningful ways. But also, what we’re not paying attention to can be the work itself. My fear is that people stop seeing and thinking about an artwork and start seeing the absence of an artwork that they’d prefer to be seeing. That the effort required in expressing ideas, and the attention required to receive them, becomes secondary to “what can I do with this?”

MSM: I think what's interesting about all of that is just the veil that we're putting over the work that's happening behind the scenes. I'm not sure how anyone can communicate that, because what we want is we want to see things that are slick and we want things to seem like magic and without effort. That probably points to class and privilege.

ES: Yeah, it has a lot to do with privilege, to say that effort doesn't matter. People really believe effort doesn't matter only if they’re able to get whatever they want without it. For example, people presenting AI-generated artworks don’t want to say that, literally, millions of people made this possible. There’s a lack of attention to things inherent in these patterns around technology.

By contrast, when you, and I mean you, look at artwork and think so deeply about process, that attention comes out in your work. But digital technology often breaks our ability to perceive that in the work.There's a tendency to act like things just happen.

MSM: It's magic! It's for me.

ES: And for certain people, having access to ways of telling their own story through another story is deeply meaningful, there’s lots of great, subversive art. I don't mean to minimize that, but there is also the flip side of that. For example, using an AI tool to create images in someone else's style. It's very simple, and inattentive, to be someone who says “well, the artist can do it, now I can.”

But there's something from the statue of Cleopatra that makes it into the poem, something that then moves into the musical performance. It's these linkages, they're very hard to trace, but they are now part of this really big conversation that we're having around generative AI and art as “remixes.” In fact, AI images are not remixes: it's vast collections of data being scraped up and autonomously analyzed, and then these patterns are digitally reproduced into new images.

And so it's a different kind of remix from the human act you described. Where, on the one hand, there's a flow of intention, a meaning, that moves from one piece into the other. There's a human moving these pieces from one form into another and grappling with that original form and then reproducing a new form. Art is a very powerful process, a personal process. A crucial point of remixes is attention. If we act like that’s an automatic process, it’s as if everything has always been a remix machine that is just spitting out remixes.

MSM: All that effort disappears.

ES: There’s a link of that phenomenon with the flags we mentioned around grief and around trauma, or around your book. The algorithm flags it because it doesn’t “get” what you’re doing with the Xerox machine. Trauma is getting flagged by social media and hidden because it doesn’t know what a human goes through. It’s protection without attention. Sometimes it's because it’s triggering, and people don't want that.

MSM: I also think the reason that these words are flagged in social media is because social media's goal is to keep you on social media longer. Once you start thinking about that, you start getting existential. You might shut down social media and take a walk. I'm sure that they have figured this out in the data. That's absolute conjecture.

Unless you're involved in a grief community or something like that, where people do spend a lot of time engaging with that kind of discourse, if it just pops up, then people bounce. I wish that it were allowed. Especially if you could just fine tune it using your own filters. To me, it's a little overbearing and maybe tending towards some other kind of, maybe we could say fascism, or something, to just block and suppress those things. It really shouldn't be happening.

Bunraku Intelligence

MSM: My question to you is what is the antidote to this problem? What is the antidote to this hiding all the work? How do we show the work? Is it that we create more behind the scenes content? There's this Japanese notion of wabi-sabi, where you leave a little fingerprint or a dent from your knuckle into the pot because you don't want a perfect pot. That’s the wabi. You want to know that a human made it. You want it to have some kind of soul.

If it's really slick and perfect, then the humanity disappears. But if it's got that little imperfection, then it acknowledges humanity and the person who made it.We're saying it comes from privilege. But what do you think the antidote to that would be?

ES: I think that's an interesting artistic question. One of them I'm thinking about is also from Japan, which is Bunraku puppets. You can see the puppet masters on the stage, which shows the work. Barthes writes about it, that if you can see what’s behind the artistry, you don’t make the artist into a God. It disrupts the illusion that the puppets move on their own.

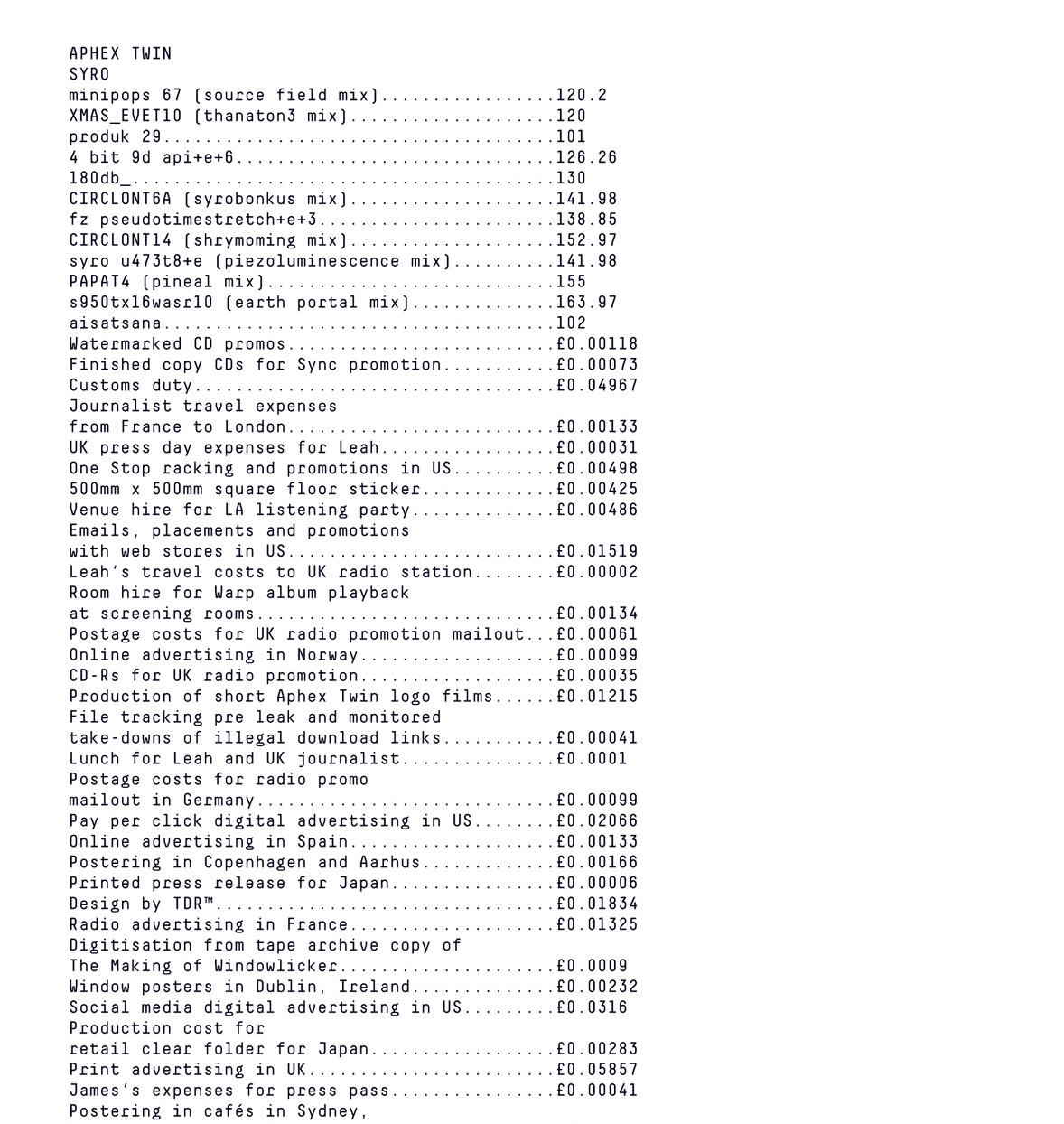

I also think about the Aphex Twin album cover for Syro. Every expense related to the production of the record was itemized - that's the album art, the list of expenses, in terms of where the money spent on the album was going. The fingerprints of production and marketing teams! So there are different strategies to that, which say different things.

MSM: And then what's the appetite for that? How much of that before overwhelm sets in and viewers can no longer engage? Which is the whole reason why I like to use the head fake. Because that overwhelm can take over if you're being a little too honest or a little too upfront about what's going on there. That's the whole reason that we don't only write books. That's the whole reason that we make films and we make music, because we're trying to get at something that's underneath all of that.

ES: Yeah. And there is that element of, I don't know if I want to say, like, seduction of the viewer. Then — surprise! It's actually all scaffolding!

MSM: It’s the Truman Show.

ES: Is there a parallel to this with the way that people often feel that they have to respond to their own trauma, to their own grief — as in, not to reveal it? There's nothing wrong with privacy. I’m talking about social pressure or shame. There is a commonality between those pressures, the polish that you get on social media algorithms, and the polish you get in flat generated artworks that don't have process behind them. Everyone must get along well, for everything to seem smooth, it has to be polished and presentable, as opposed to the complexity of superposition that you've been bringing up, I think, where things can be simultaneously polished and painful.

MSM: Right. Things can be multiple things at once. And we're so bad at that. I mean, how do we hold things up in a matrix? It's so difficult. We need the thing, we need not the thing, and we need the third place, which is both of the things and maybe the fourth place, which is neither of the things. We need all of those at once.

ES: And the thing that was there that has been removed, that is different from the thing that has never been there.

MSM: The reality of the history. It's the people's history and the reality. We don’t do this because it’s overwhelming. It takes up so much brain power and we're not used to it. We want stories to be straightforward. I’m reminded of “The first sentence is five words. The second sentence is five words.” It’s this formulaic copywriting tool. People use this because of this particular formula. Who wants to write like that just because it works and just because we understand it? Or even if the story gets across better that way. Why are we forcing ourselves to present our work in this way?

It's the struggle that artists have because more than anything we want to get our work in front of more people, but we want to be authentic to ourselves. And being authentic to myself means that even though I have a page dedicated to my first book, Grief is an Origami Swan, I cannot engage with that every day. It's too much for me. And so for me, that's my messiness. That's my being human. But I get punished for it by the algorithm. Fewer people see the work because I'm not able to engage with it every day.

ES: To “get it out there.”

MSM: There's no bolstering that any of these platforms, or any of us, can do to help each other out. Maybe it's also cultural because we're such an individualistic society in the West. Because of that individualism, if we fall behind, there's not a lot of community built into our systems. And that's what we would need to succeed. That's what we would need to show up.

I don't know that I believe in this idea of authenticity, but that's the way that we would be able to show up for ourselves in an honest way that was honest to some of these states that exist all at once in ourselves.

ES: There's a politics to that. There's definitely something in most technology that says things are messy, and when they aren't messy, that's ideal. When things are messy, you should get away from them. That definitely gets in the way of the messiness of coming to a community decision, or the messiness of figuring out what kind of emotional support or resources people need. Silicon Valley individualizes everything. With GPT4, you don’t need a crew of people to write a policy proposal, you can do it yourself. Something really important gets lost when we have the power not to pay attention to people.

MSM: That speaks to ways that we have to come to in transformative justice and restorative justice. All of that is super messy. But, to me, it's like what they say, how do you heal? It's so much easier to heal a wound that's jagged. That messiness is productive.The mess of collaboration helps us work out the kinks and it helps us spend more time with each other in community.

ES: The “work in progress” is political.

MSM: I love that.