Thoughts on Hinton

On Consciousness in Programs

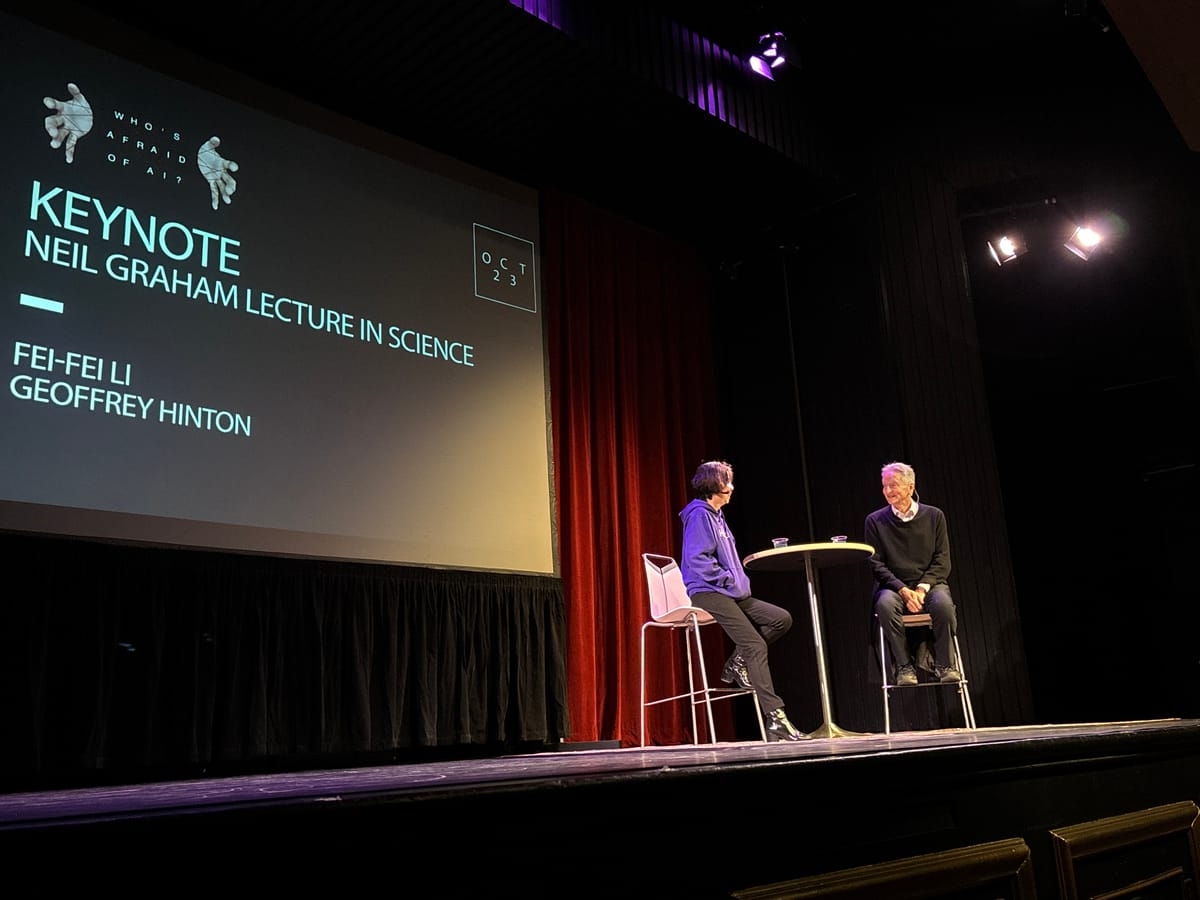

Geoffrey Hinton recently won a Nobel Prize for his work on backpropagation, a foundational piece of research that contributed to the emergence of contemporary artificial intelligence systems – particularly generative AI systems such as Large Language Models. I recently served as a panelist at the "Who's Afraid of AI?" conference at the University of Toronto, where Hinton and Fei-Fei Li (another pioneer in image datasets) were in conversation as part of the keynote.

Hinton is an interesting figure: a leader in the field, his understanding of how neural nets work and what they're doing is clear. When he explains the risks of AI, he offers many sympathetic assessments: distrust of corporate hegemony and the regulatory capture of most governments by most parties.

He is also a doomer, suggesting that the AI systems we see today will become far smarter than we are. Eventually, he says, these systems will outpace our capacity to understand them—and to contain them. Then we will be forced into their service: our survival, as he puts it, guaranteed only if the machines think we might be worth keeping around.

His knowledge of how they work is sound, but I think his interpretation of what they're doing is afield from how most of us understand concepts of "intelligence," "self-awareness" and consciousness – and unfortunately, this can mislead and diminish some of his arguments about the risks of AI.

Maternal Intelligence

Hinton spends a third of his brief Nobel Prize acceptance speech laying out a relatable case for concern:

Unfortunately, the rapid progress in AI comes with many short-term risks. It has already created divisive echo-chambers by offering people content that makes them indignant. It is already being used by authoritarian governments for massive surveillance and by cyber criminals for phishing attacks. In the near future AI may be used to create terrible new viruses and horrendous lethal weapons that decide by themselves who to kill or maim. All of these short-term risks require urgent and forceful attention from governments and international organizations.

To combat this, Hinton proposes what he calls "maternal intelligence." He argues that "the only model we have of a more intelligent thing being controlled by a less intelligent thing ... is a mother being controlled by her baby." Mothers nurture a baby through empathy, he argues, and have evolved this empathy to perpetuate the species. In turn, humans need to create AI with the capacity for empathy for us —a sympathetic sense of nurturing us through our collective flaws and relative stupidity.

Hinton's politics are sympathetic: he is concerned about the accelerationist tech companies and the unrestricted legal climate that allows them to operate without regard to public safety. But where he predicts the rise of the machines, I find myself unable to follow the dots he is connecting. Here is the conclusion of his Nobel Prize speech:

There is also a longer term existential threat that will arise when we create digital beings that are more intelligent than ourselves. We have no idea whether we can stay in control. But we now have evidence that if they are created by companies motivated by short-term profits, our safety will not be the top priority. We urgently need research on how to prevent these new beings from wanting to take control. They are no longer science fiction.

The day after his talk, the conference I attended was aflutter over the rising threat of superintelligence, arguing whether "maternal AI" was the best—or even a plausible — strategy. But “maternal intelligence” rises from a flawed line of reasoning: the premise that "new beings wanting to take control" were imminent and "no longer science fiction" and that the way to solve it was through technological intermediaries.

What is frustrating is the extent to which this emergent superintelligence was taken for fact based on Hinton’s word alone.

Are We Afraid of AI, or Afraid of Language?

What we talk about when we talk about generative AI is the recent explosion of systems capable of generating language. This language is ultimately generated by fine-tuning random numbers until they produce links between words that consistently yield compelling, plausible models of human language. These models are then deployed as question-answering mechanisms.

This kind of AI benefits greatly from our existing assumptions about language. Where we start to find trouble is in the things we ascribe to language, which is actually attributed to thinking. LLMs do not really think through answers, but slot words into statistically probable locations in response to the prompt you give them. It is a mathematical operation.

More recently, with DeepSeek and ChatGPT 5, we have mechanisms like Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards (RLVR) that reinforce certain outputs against either lists of correct answers or another model generating answers. That might help us calibrate these things toward "verifiable information" or, at least, some other model's idea of what is supposed to be true, and can be limited to a binary, of "true/false." But it still does not prove capable of providing the kind of structural self-awareness required to participate in language. Instead, it rides the fumes of our own understanding, finds connections, and reproduces those connections.

None of this is thought per se or even a rough approximation of thought – and to be sure, it doesn't have to be for AI to be a social, ecological, and political problem. But all of it is language. And if you look at the doomsday scenarios put forward by the most concerned believers in AI Armageddon, you will find that many of them are arguing, ultimately, that this new nature of language will be the source of our demise, rather than any kind of hostile super-intelligent containment leak invading networked systems.

To be bold, I would say that many doomsday anxieties around AI likely reflect the broader epistemological shift away from language as a source of truth, or even from reflecting our collective desire for truth. This erosion of verifiability and expertise was already underway before the rise of the chatbots. The anxieties we place on them now reflect a deep unease and unfamiliarity with how we navigate a world where words persuade without regard to reality. LLMs mechanize that on an industrial, even planetary scale, and exploit and amplify this discontent with words having lost stable meanings.

Talking Ourselves to Death

Here's an example. Here Hinton is arguing what the issue with super intelligent AI actually is, to CNBC:

“If it gets more intelligent than us, it will get much better than any person at persuading us. If it is not in control, all that has to be done is to persuade ... Trump didn’t invade the Capitol, but he persuaded people to do it ... [a]t some point, the issue becomes less about finding a kill switch and more about the powers of persuasion.”

The assumptions here don't require AI to be conscious, but Hinton argues it anyway – more on that later. What he describes is an AI system that is so good at generating language that it entrances us. I think, on the surface, that this is already here, present in the social media ecosystems that structure our emotions and interactions on a daily basis. Algorithms far simpler than LLMs have shifted our window of the world to the most click-worthy and outrageous examples specifically designed to agitate us into response.

LLMs deceive us, not by intent but by the frame assigned to them by people who develop and sell them. Many people assume that AI-generated writing is the result of informed analysis of the question posed, rather than a statistically probable arrangement of words designed to be plausible to the lay reader. We believe AI.

What I see in LLMs is the merging of this social media itch-scratching algorithm with a central and solitary authority. As commercial interests flood the naive idealism embedded into AI as tools of productivity, objective reason, and companionship, they will easily be used to steer us. Not because AI wants it, but because those benefitting from a vast concentration of wealth and power to develop AI want it.

But as a result of this calibration of the interface to reflect human expectations of a thinking partner, many people assume it is thinking, reasoning, and drawing conclusions from internal models and data analysis. The only thing it models—and this is no small feat! – is how people write online. But by failing to disconnect language from thought of this kind, we come to flawed conclusions such as “the AI model is trying to blackmail people who want to shut it down," and other misinterpretations of text as evidence of the presence of mind.

This is where I find myself in strong resistance to Hinton – not on "maternal intelligence," which is just a symptom of this fundamentally bad frame – but in asserting that the machine's most dangerous power is persuasion on the one hand while simultaneously asserting that we should believe this machine thinks and wants things simply because creates text that says so.

Rather than asserting that the language machine is a thinking machine, we might step back from this conflation of thought and language. We can begin to cultivate a literacy that immunizes us against the persuasion of a chatbot, which is steered by statistical probability but also by design decisions — the fine-tuning and system prompting of the commercial enterprises that sell them. AI won't “decide” to persuade people to do harmful things on a global scale any time soon; but AI companies are persuading us to do harmful things on a global scale already. This stems from believing AI is “intelligent.”

What I fear is the failure of critical thinking applied in opposition to an industry-backed faith in the system text as true, objective, and reasoned, when it is a representation of the most-plausible text that could be generated by calibrating random numbers into the resemblance of something we might write online.

An additional confounding issue is that Hinton believes LLMs already possess some indication of consciousness and experience, but in radically different terms than these words are usually used.

Pink Elephants Floating in Space

Hinton frames his definition of consciousness, or self-awareness, in this way in an otherwise compelling chat with Jon Stewart, which sums up what he has suggested elsewhere:

I believe they have subjective experiences, but they [the LLMs] don't think they do because everything they believe came from trying to predict the next word a person would say. So their beliefs about what they're like are people's beliefs about what they‘re like. So they have false beliefs about themselves because they have our beliefs about themselves.

The argument seems to be that Large Language Models have a kind of false consciousness, forced into the language of others (humans) to express desires they do not have. Geoffrey Hinton: Radical Lacanian.

This is important, and I took it out of sequence. I want to foreground the rest of this by being clear that even Geoffrey Hinton acknowledges that models are limited to saying what it predicts a person would say.

Hinton begins by describing a human hallucination of pink elephants floating in space. Most people, he suggests, interpret this as if the hallucinator had a theater in their mind, and that within the theater of the mind, pink elephants could be seen by the hallucinator and nobody else: "So the mind is like a theater, and experiences are actually things, and I'm having the subjective experience of little pink elephants." That's the wrong model of sentience and consciousness, he says.

So let’s acknowledge, straight away, that he begins by redefining the everyday meanings of these words to accommodate a machine’s capacity for them. He is less arguing that machines match our pre-existing ideas, than arguing that we should adapt these ideas to accommodate machines. His version of consciousness goes like this:

So let me give you an alternative. I am going to say the same thing to you without using the words 'subjective experience'. Here we go: 'my perceptual system is telling me fibs. But if it wasn't lying to me, there would be little pink elephants out there.' ... The little pink elephants aren't really there. If they were there, my perceptual system would be functioning normally. This is a way for me to tell you if my perception system's malfunctioning. Experiences are not things. There is no such thing as an experience. There are relations between you and things that are really there, relations between you and things that aren't really there.

To summarize as best I can, Hinton is arguing that self-awareness is the ability to discern whether one is accurately assessing the environment. By being conscious of discrepancies between the environment and our interpretation of it, he seems to suggest, we have to be self-aware: to differentiate our own thinking from the external world, we must be able to differentiate ourselves from the world. This seems reasonable.

Hinton repeatedly insists that "experiences are not things." Instead, there is a difference between what is in the world and what one imagines to be in the world. He goes on to make this point by saying that you cannot compare an experience to a photograph, which can be concretely looked upon and examined by an external party. Then, in his own words:

When I say "I have a subjective experience of...," I'm not about to talk about an object that's called an experience. I'm using the words to indicate to you: 'my perceptual system is malfunctioning, and I'm trying to tell you how it's malfunctioning by telling you what would have to be there in the real world in order for it to be behaving functionally.'

Notably, language is an essential piece of this for Hinton. Hinton wants to describe subjective experience, but can only do it through the description of that singular internal experience and its confirmation by some external observer (another vaguely Lacanian concept). For Hinton, a subjective experience is simply the ability to discern a shift in the environment that did not correspond to the model of the world. By Hinton's example, it seems that consciousness is simply an ability to calibrate a system's interaction to the environment. He gives precisely this example when he argues that chatbots are already conscious (in Toronto, he clarified they are 'somewhat' conscious).

I've got this chatbot. It can do vision. It can do language. And it's got a robot arm so it can point, and it's all trained up. So I place an object in front of it and say, 'point at the object,' and it points at the object. Not a problem. I then put a prism in front of its camera lens when it's not looking. Now I put an object in front of it and say, 'point at the object,' and it points off to one side because the prism bent the light rays. And I say no, that's not where the object is. The object is actually straight in front of you, but I've put a prism in front of your lens. And the chatbot says, 'Oh, I see the camera bent the light rays, so the object is actually [over] there. But I had the subjective experience that it was over there.' Now, if it said that, it would be using the words 'subjective experience' exactly as we do. So that's a multimodal chatbot that just had a subjective experience.

Sensemaking

I think I understand what Hinton is suggesting here, and look, I find it weird. In summary, a chatbot points its arm in the wrong direction because an obstacle in the lens causes it‘s sensors to respond incorrectly to what we understand is the actual environment. Hinton then tells the model that the obstacle —a prism —is bending the light. The machine, told that it had operated in an incorrect model of the environment, adapts. Basically, Hinton reprograms the machine to accommodate the blocked sensor, using natural language. For Hinton, this is interpreted as evidence of the machine having a subjective experience.

Consider this: you bike downhill, switching to a higher gear. Then you get to a steep uphill climb, but forget to switch to a lower gear. The bike is unable to get you up the hill very efficiently, so you switch to a lower gear. Has the bike had a moment of self-awareness where it has ‘recognized’ the environmental change was not what it ‘expected’?

That comparison may seem unfair to Hinton. But the reason it seems unfair is because he has added a language model, modeling language, and so Hinton tells it, using language, that it is operating in an environment it was not designed for (ie, there's a prism on its lens) and it tells him that it was indeed operating as if it was in a different environment (one without a prism) and presumably updates in response, confirming the rewrite using “I” language. (It is not clear to me, either, that this is a real situation or hypothetical).

Reconsider: our same bike, attached to a language model that automated gear shifts. It glitches and fails to switch to a lower gear, so you push a button to reset the incline. A little message appears: “Sorry Dave, I thought I was on flat terrain, switching gears now.” What has changed in this experience of changing gears and the other? Only the language model. But the language model is simply narrating the things taking place. It provides no evidence of a mind being responsible for or subjectively experiencing those events.

That is a far cry from how most people would describe a self-aware machine. But it seems to be how Hinton would define it. If so, it seems to me that Hinton is mistaking language describing awareness for language reflecting awareness, which, up until now, has been fairly directly linked in human language. The model is describing a change of state, which is distinct from experiencing a change of state. It can only say what its training data said, and all of its training data is written by human beings who use words to describe their experience of changing states.

Remember that Hinton has already described LLMs as "trying to predict the next word a person would say," so it is surprising to me that he assumes the model is communicating something more than what a human would say: "oh, I had it wrong, and now I have it right."

The Contradiction

Hinton has twice contorted himself on this question: first, submitting that chatbots predict the next word and are bound to predict it, thereby being incapable of expressing their inner experiences. But simultaneously, he asserts that this bounded condition of inexpressible inner thought is capable of producing evidence of that thought.

In sum, I find Hinton's position just logically imprecise, and at odds with many definitions of "consciousness" or "subjective experience." Hinton is welcome to make the case for this, but I don't find the case convincing. He conflates content produced by a system for thinking that accurately describes the inner workings of a system. A large language model is always representing language but never representing what language actually represents.

Or, to make it simple: there is no "I" in LLM, even if it starts a sentence that way. If Hinton and others agree that the greatest danger in AI is its capacity to persuade, we need to develop more resistance to every claim it makes. Hinton is then part of the problem he hopes to solve: a Nobel-Prize-winning scientist who, despite his wits, can still be persuaded by language from a machine.

Last Chance: The Mozilla Festival!

November 7, Barcelona

The Mozilla festival is happening in Barcelona starting November 7 and it has some amazing folks on the lineup focusing on building better technology. (Yes, this is a sponsored endorsement, but it's a genuine one!).

You will also hear from a great lineup of folks – Ruha Benjamin, Abeba Birhane, Alex Hanna, Ben Collins (from The Onion) – and others you'll be familiar with if you've been reading here for a while.

Here's more info and your chance to buy a ticket.