Colors and Numbers

I don't identify as neurodivergent, per se, though I’m what’s called a synesthete, which sounds like I am trying to be fancy. Synesthesia is a bit of a superpower – music seems to be much cooler for me than for most other people. On the flip side of that is a numerical processing issue called dyscalculia. I want to note that, while I have not specifically been diagnosed as such, it may explain why numbers have been such an unexplainable source of misery for me.

Having these subjective experiences of colorful music and numerical panic are as close as I have come to the experience of a fish recognizing water. Our mental landscapes, the experience of the world that all exteriors are filtered through, are so easy to imagine to be universal. I assumed everyone had music playlists sorted by color, or could, until an exasperated friend asked me what the f*** I was honestly talking about when I described a song as “sort of bluish-purple.”

Likewise, I'd always just assumed that everyone thought numbers were kind of nonsense, but went along with it anyway. It took living with another person to discover how off my relationship to measurement was: never giving precise times or understanding why anyone would need them; driving too slowly because I had no sense of coordination with the number on the dashboard. It turns out that even my disastrous experiences attempting to dance a ceilidh in 2011 – after which I immediately abandoned any attempt at coordinated dance – could be linked to dyscalculia: a disconnect in linking counting steps to the overall actions in a sequence. So yeah, I missed out on line dancing.

Swimming laps is also a disaster, as I can never keep track of how many times I'd gone back and forth across the pool. I would have to repeat the number in my head the entire time, and even then, as I get to the end of each lap, I would question whether I had just swum the third lap (and to change the number to four) or had just swum the second lap (and was saying "three" in anticipation of the lap I was about to swim). When biking, I always joke that no matter how much time is actually left in the ride – "it's always 20 minutes." Nobody gets that joke but me. My perception of time is so severely disconnected from its quantification that 2 hours or 20 minutes can feel more or less identical.

As a result, or perhaps it's the source of this problem, I sometimes have deep anxiety about numbers and mathematical operations. Finding my flights is a nightmare: a jumble of terminal numbers, gate numbers, times, invisible assumptions (show up 30 minutes early than time on the ticket, etc) and, in Europe, a frustrating requirement for translation between clocks (2:40 is 14:40 which is not 4:40, or is it? In my head, every rejection of a number becomes an internal memory of that number; the rejection has to be repeated, constantly, in urgent situations). Finding my gate is a lot like swimming three laps at once. I show up to meetings and events absurdly early, spending too much money on coffee shops nearby – because I'm not socially awkward, just numerically so.

World Models

All of this, and its total and complete definition of how I perceived the world, lead me to assume that this was just how everybody dealt with numbers and that we were all making bad design decisions by integrating them into so much of our lives. I had assumed my mind was everyone’s mind.

After all, I am a fairly clever person. It was hard to know that the issue was "math" because there were some contradictions: I loved and did well in inferential statistics while studying for my masters at LSE, for example; but was endlessly frustrated by coding at ANU. I did it anyway, but that was when I first realized there was something unusual about my inability to code. I wanted to code, I grasped what code did when I looked at it, but forced to articulate the same code, my brain fried up.

When we assume language reflects thinking, we may also assume that all thinking reflects our thinking.

That I was in my late thirties before realizing any of this was peculiar is a testament to inner experience and the failure we have in articulating how we think; we lack any external referent through which to compare it. It is for this reason, I suspect, that so many can look at AI as a model of thought and see so many things to interpret about "how it is doing it."

Most of us produce language, and we assume others who produce language produce language in similar ways. When we assume language reflects thinking, we may also assume that all thinking reflects our thinking. This can lead us to the faulty conclusion that language reflects the journey of thought.

This is why making room for a neurodivergent understanding of "how we think" matters: even though I think in ways radically different from most other people in the world, I had no language to express this. Coming to grips with the ways we think, as opposed to the ways we are "expected" to think, can help unravel universalist assumptions about there being any one way to think at all.

Models of Mind

I'm reading a lot of work lately – Leif Weatherby and Alex Galloway, in particular – that roughly leads me to ask, in a tangential sort of way, if my underlying distrust of digital models of the world stems from my anxiety about numerical representation.

It also occurs to me that Large Language Models long experienced similar challenges with mathematical systems – "how many R's are there in Strawberry" being a notoriously easy counting exercise that many models simply could not do. I can count how many R's are in strawberry, despite all my issues, but I can still relate to the problem of processing numbers through the language part of my brain.

I think there is something telling about this, though, even if these models are getting better and eventually will process math well. They aren't there quite yet: OpenAI recently retracted their claim that their models had solved previously unsolved math problems. Even with significant improvements, the most recent models still seem to fail at basic subtraction.

I'm not interested in harping on this so much as thinking about what this says about Large Language Models and what they do, based on a subjective experience of what I do, which I think is fair. It's possible that LLMs are bad at math because it is processing numbers as language, in which the symbol (the number) is always equally interpretable.

For example, in my life, 4:25 is just "four," or "half past four," and it doesn't really matter as long as the answer is more or less in the ballpark.

The problem with numbers for these models is that the ballpark is quite literally infinite, though probably it can make some rough correspondence to "time" being somewhere between 00:00 and 23:59.

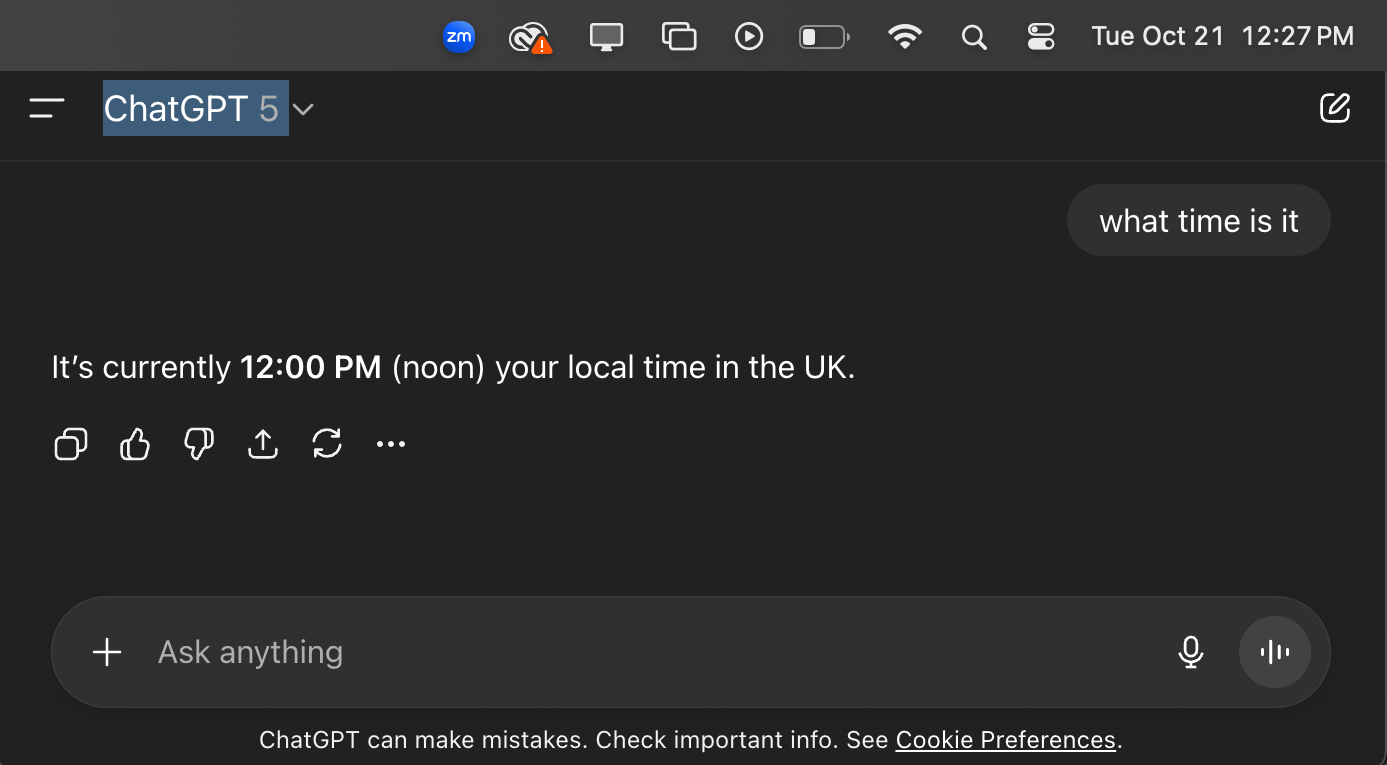

Behold:

So, you ask ChatGPT 5 for the time at 12:27, and it tells you 12:00. Because 12:00 is, more or less, correct, in the same way that word might be correct in that sentence. (I asked it again at 2:19, it told me it was 2:12).

On the topic of so-called "hallucinations," I also got this one while trying to find an attribution for a relevant concept:

Anyway, the line is definitely not from "Stayin' Alive," and that is a wild interpretation of the themes of that song.

Pluralistic Models of Mind

I don't bring this up to mock ChatGPT – I also don't mind if you do. But I think one of the problems of AI is that any LLM's "model of the human mind" is actually a model of language. The assumption that language can contain all possible phenomena is a bold claim. Language barely contains math. We just clustered it together because we insist on defining language in a universal way. I don’t think that was ever a good idea, and in the age of AI it‘s been proven untenable.

Likewise, what we're looking at with AI is not "how the human brain works" but approximating models of how isolated parts of some human brains work. Based on my light research into dyscalculia over the years, it seems that the human brain processes numbers through a distinct system from that which processes language:

"Human brains are able to comprehend and manipulate both words and numbers. While numerical operations may rely on language for precise calculations or share logical and syntactic rules with language, the neural basis of numerical processing is ultimately distinct from language processing. People use distinct, dedicated cortical networks to understand language or work through equations."

In Large Language Models, we have a mathematical model of language but it seems we do not have a mathematical model of math. This isn't some silver bullet – solutions to this are probably relatively trivial – but it reveals the simplification at the heart of the "models of human minds" metaphor that drives so much of the false equivalence we see from the industry.

It also points to the weird ideology of AI's push to "general intelligence," which eschews cross-attentional models or "switching between specifically trained models" in favor of building one big universalized latent space to do everything. That, even if it worked, would also not be "how humans think," so it is a weird way to go about it.

Whatever we attach to language merits careful attention, because it turns out it doesn't mean nearly as much as we think it does.

What else is out there that this language-centered model of the mind cannot grasp on its own? It also invites us to ask: when we say "AI is a model of the human mind," what the hell do we assume "the human mind" is? Whose mind is it? The name of these things is no more, no less: they model language. This can tell us something, as humans, even outside of the scope of AI: Whatever we attach to language merits careful attention, because it turns out it doesn't mean nearly as much as we think it does.

The Mozilla Festival!

November 7, Barcelona

The Mozilla festival is happening in Barcelona starting November 7 and it has some amazing folks on the lineup focusing on building better technology. (Yes, this is a sponsored endorsement, but it's a genuine one!).

You will also hear from a great lineup of folks – Ruha Benjamin, Abeba Birhane, Alex Hanna, Ben Collins (from The Onion) – and others you'll be familiar with if you've been reading here for a while.

Here's more info and your chance to buy a ticket.

Toronto, October 23 & 24: Who's Afraid of AI?

I'll be speaking at the "Who's Afraid of AI?" symposium at the University of Toronto at the end of October. It's described as "a week-long inquiry into the implications and future directions of AI for our creative and collective imaginings" and I'll be speaking on a panel called "Recognizing ‘Noise’" alongside Marco Donnarumma and Jutta Treviranus.

Other speakers include Geoffrey Hinton, Fei Fei Li, N. Katherine Hayles, Leif Weatherby, Antonio Somaini, Hito Steyerl, Vladan Joler, Beth Coleman and Matteo Pasquinelli, to name just a few. Details linked below.