We Might As Well Get Good At It

A new documentary on Stewart Brand asks where techno-optimism has gone

This week I am in a few places at once. I'm attending a two-week course at the Cambridge Cultural Heritage Data School in the UK. I'm attending South by Southwest in Austin, Texas. And I'm working on an event for Melbourne Design Week in Australia. And I'm walking my dog, often. We’re tired of screens, the mediation of technology, and yet, they have obviously widened the scope of my pandemic life in incredible ways.

This balance of shadow and light in technology is central to the film “We are as Gods.” The documentary, on technologist and futurist Stewart Brand, premiered at SXSW this week. Brand is behind The Whole Earth Catalog and The Long Now Foundation. He's also working to bring Wooly Mammoths and Passenger Pigeons back from extinction.

Brand is controversial, the kind of guy who gets scary music played behind him in Adam Curtis documentaries. He holds unorthodox views on the necessity of nuclear power and biological engineering. Curtis pitches Brand as a naïve tech visionary, and to a lesser extent, so does “We are as Gods.” The title comes from the slogan of the Whole Earth Catalog:

“We are as Gods, and might as well get good at it.”

Here, Brand presents a bewildering argument. He suggests that tech is full of good hearted folks interested in solving problems.

This is the voice of a man who was part of the hacker community of the '70s and '80s. It reflects the kind of internet Utopianism prevalent in the '90s (Brand was there, too, and almost everywhere else). But by 2020, we know what greed has done to ideals. They've commodified them, warping them into drivers of social and environmental harms.

"We are as Gods" suggests that Brand's optimism is more useful than his skeptic's pessimism. It frames the debate around one question: Should we breed elephants with mammoth DNA and restore the arctic biome of the Russian steppe?

In the film, we hear from the critics. Something will go wrong, because something always does. It's hard to disagree. But the easiness of that idea is a good enough reason to imagine things in some other way.

I've heard this argument before. I live in one of the reddest states in America: 60% of Tennessee voted for Trump in 2020. There's an argument I hear from conservatives here. “Government does a bad job at everything, so it shouldn’t do anything.” The idea assumes that we could never create a functional government, so why try?

That's a position of hopelessness. It rejects the very concept of “good ideas.” And it finds surprising parallels in environmentalism. Much of the environmental movement rejects technology as a solution for stewardship. Fearing catastrophic failures of complex, difficult engineering and design challenges, we mistrust any attempt to solve problems with new tools. From there, it's tempting to retreat into a “unbuild” frame of mind. Or to give in to despair, which helps no one.

Technology is not, itself, a solution. Not in our current arrangement of incentives. The problem is not technology, either. It’s the distorting effects of its birth site, emerging from Silicon Valley’s blend of profit seeking, antisocial behaviors cloaked in ideologies of individualist liberation, and a limited ability to imagine anything else could be good. How could we design technology around a different set of positions? What incentives would motivate the design of genuinely safe, autonomous, environment-restoring technology?

I am a tech utopian in the long run, but we need to reroute the train tracks. That requires challenging every tiny step we take to ensure that train is headed in the direction we want. It’s easy to lose myself in cynicism. And while critics dismiss Brand’s tech optimism as “naïve” in the film, it might also be necessary.

We need optimism to imagine new means of designing and scaling these technologies. We need cynicism to protect ourselves from overreaching.

R. Buckminster Fuller and Shoji Sadao, Dome over Manhattan, 1960

Things I’m Reading This Week

- A Bestiary of the Anthropocene

Nicolas Nova & Disnovation.org

A new book (I have only read the review) wherein artists attempt to catalogue bio-technological systems, which leaves me uneasy, and yet, fascinated and hopeful. Examples include the ubiquitous “tree cell phone tower” to eagles that attack and destroy drones. From a review:

Our techno-fetishism has done a lot of harm to ecosystems. Fortunately, some techno-enthusiasts write, more innovation or more living creatures transformed by innovation will solve any spot of bother and humanity will be allowed to breezily carry on as usual. Cue to the worms that digest polyethylene and the fungi growing in Chernobyl’s former nuclear power plant site which are now being used to help shield astronauts from radiation.

The book seems a bit more critical than the review implies, framing its question as “What happens when technologies and their unintended consequences become so ubiquitous that it is difficult to define what is “natural” or not?”

- Defuturing the Future

Andrew Blauvelt

In September 2020 the Walker Art Center opened an exhibition presenting a series of visions about the future undertaken in 2019, before the pandemic hit. In spite (or because) of that, it’s well worth visiting online. It defines “defuturing” as design’s tendency to set us on one track that deprives us of alternatives:

Just as acts of design make the future, they can also unmake other futures. Consider, for instance, the way the design of the automobile affected the design of many other things (landscapes, highways, cities, homes) and led to certain consequences (air pollution, traffic accidents, ride sharing, climate change) that in turn foreclosed other futures. … Design’s propensity to defuture is rooted in its capacity to fulfill present wants with little attention to future needs.

- A Larger Reality

Anthony Dunne

Related:

"With few exceptions, at the heart of most current approaches to design education is a zealous focus on being realistic. By thinking within existing realities — whether social, political, economic or technological — the ideas, beliefs and values that have gotten us into this very difficult situation are reproduced through design, endlessly. Yet the underlying logic driving the labelling of certain ideals, hopes and dreams, as real and others as unreal is rarely challenged or even questioned, leading to the ongoing suppression of the design imagination."

- Queer Muslim Futurism

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto

A look at artists who identify with “Queer Muslim Futurism,” from the SF Bay Area to Berlin and Pakistan.

Queer Muslim Futurism is a reclaiming of our stories. It points out problems and names our oppressors while, at the same time, creating spaces for healing. It is not idealistic; every world we have created may be born of bloodshed, but it’s what we do with those histories of bloodshed that provides the arc of each story.

Marginalia

Where does the word ‘cynic’ come from?

According to Guy Davenport:

“[Diogenes] studied philosophy under Antisthenes, a crusty type who hated students, emphasized self-knowledge, discipline, and restraint, and held forth at a gymnasium named The Silver Hound in the old garden district outside the city. It was open to foreigners and the lower classes, and thus to Diogenes. Wits of the time made a joke of its name, calling its members stray dogs, hence cynic (doglike), a label that Diogenes made into literal fact, living with a pack of stray dogs, homeless except for a tub in which he slept. He was the Athenian Thoreau.”

The Kicker

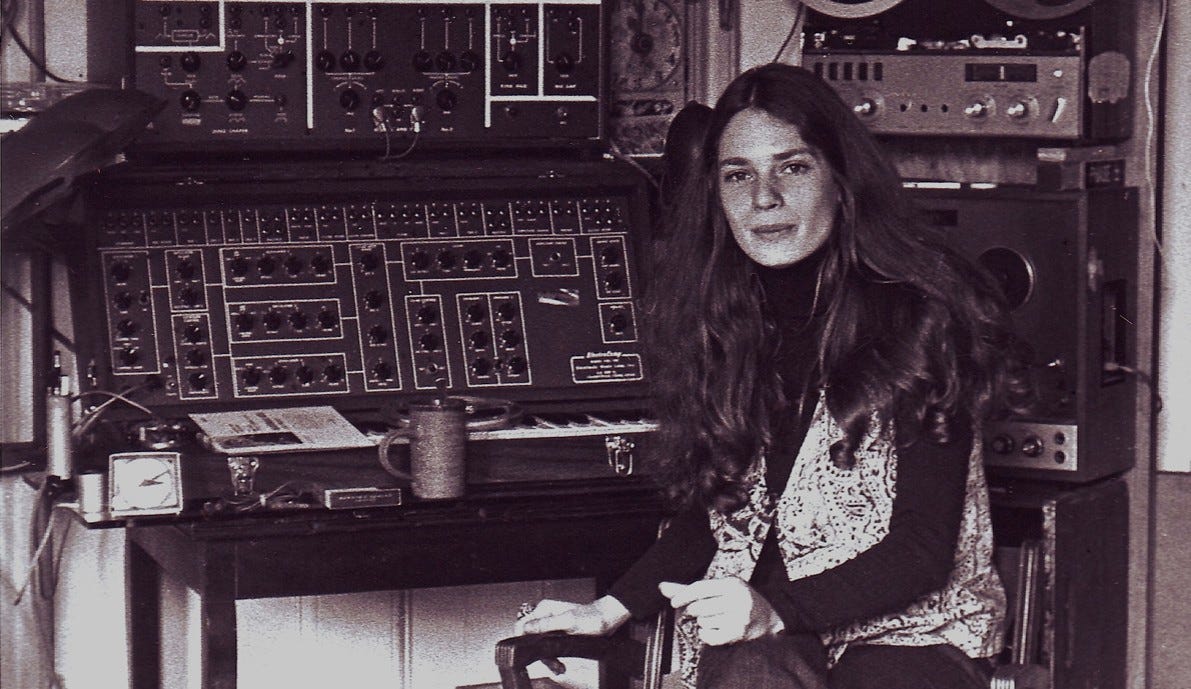

Go make music instantly using Tero Parviainen’s web-based version of electronic music pioneer Laurie Spiegel’s Music Mouse software. Created in 1986 for Atari and Amiga computers, it literally converts any movement you make into a listenable chord progression. It’s a lot of fun. (Just remember that you have to press “escape” to get your own mouse back). Read more about Spiegel’s career at Bell Labs.

Thanks, as always, for reading. Please share freely if you are so inclined.