What's Imagination For, Anyway?

Beautiful pictures of control

I had a really great time speaking at the Art Gallery of Guelph, care of the Musagetes foundation and Arts Everywhere, as part of the CAFKA festival up in Ontario this week. After a talk, I shared a retrospective of videos I’ve made for The Organizing Committee since 2020, including this one, for a new track called “Ars Electronica.”

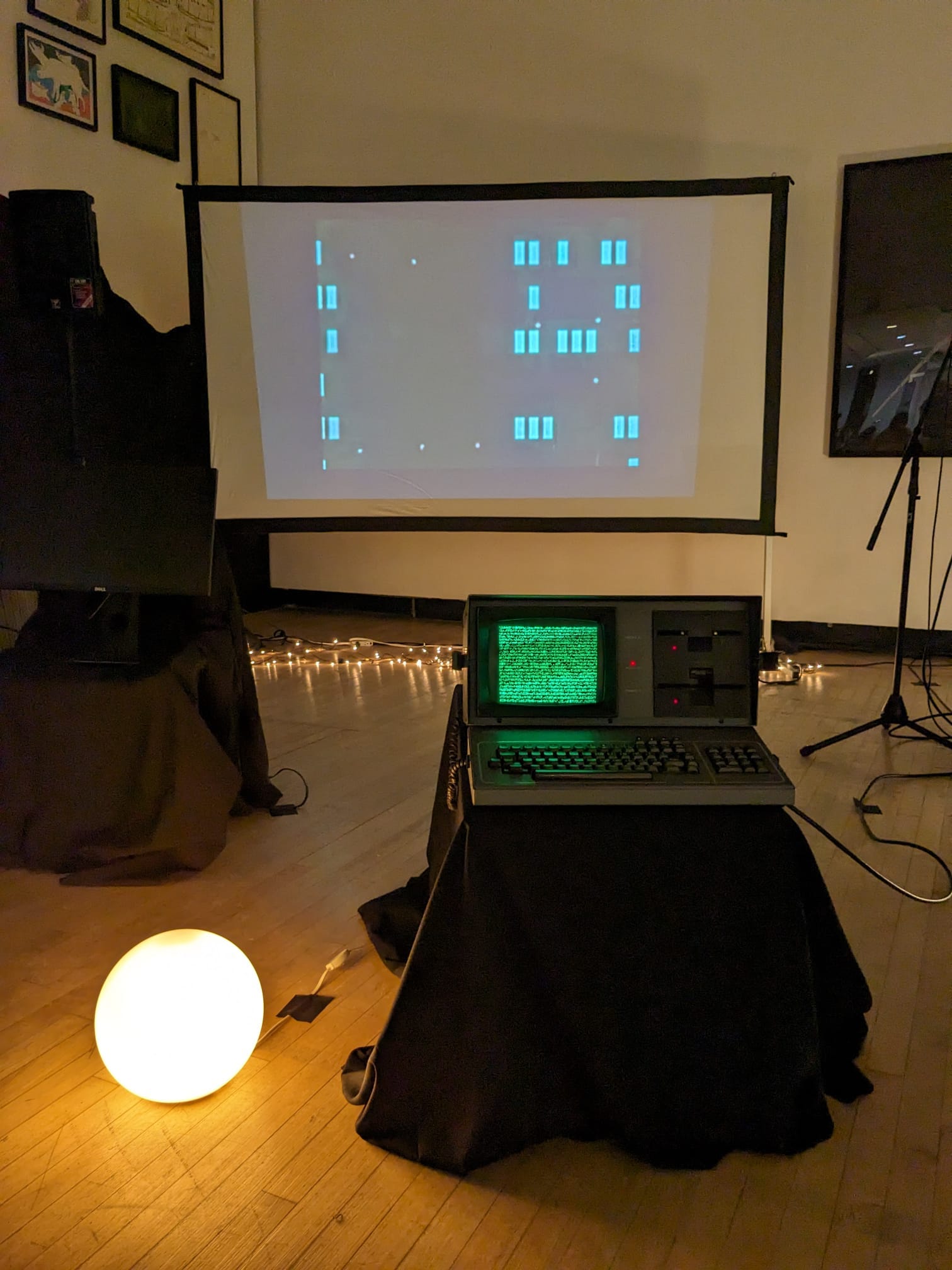

I’ll share the video of the talk when it’s available. Most notably, during the “performance” of The Organizing Committee, my Kaypro-4 — a 1981 “portable computer” that was on stage in lieu of any human performer — started smoking as soon as “The Day Computers Became Obsolete” came on.

Counter intuitively, it smelled floral and familiar, rather than the acrid scent of black smoke or the hot-radiator smell of a capacitor or burning dust.

It was the scent of incense I’d bought at Sanjūsangen-dō, the Kyoto temple known as “the hall of 1,000 Buddhas.” I keep a box of the incense and sometimes light it on a shelf next to the Kaypro, and at some point a fragment must have fallen into the computer’s rear vent. In the end, incense from a Buddhist temple getting reignited by the heat of a circuit board. It was a lovely bit of serendipity that I could not have planned for.

The new track - and video - came from thinking about artists, technology, and “the imagination.” It is the result of a mix of wake-up calls about the relationship between AI ethics and artists, and some subsequent hand-wringing.

The video is a deepfake-generated fusion of my face with the faces of Sam Altman, Mark Zuckerberg, Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates, mouthing along to lyrics (sung by a computer) about the sometimes cozy relationship between big art and big tech.

I figure these guys have taken plenty of data from us, so maybe I could take a bit of their data back for me. The tech titans got my haircut, sometimes my beard, and we all sing my lines while wearing my Stereolab t-shirt.

There are levels of complicity that we all negotiate as artists working with technology. Chief among them is that any practice involving a computer involves some company: I have a Microsoft desktop, an Apple laptop, I use Google’s Chrome browser, post on Meta’s Instagram, etc. Everything I do is happening in ways that are intertwined with the tools I use. With AI, it feels even more complicit: as critical as I am of these systems, I still rely on, and give money to, Midjourney and OpenAI and Runway to make the work.

But there’s a long entanglement of tech art and corporate tech, from Bell Labs to Google Labs and now OpenAI’s Artist in Residence. Most of the history of AI art will be written by whoever ends up in these labs. And the folks who end up in these labs are rarely surfacing meaningful critiques.

The reason to have an artist in a lab is to get that outsider perspective. But if you only bring in the folks approved by management — well, you’d better hope the managers are open to hearing new ideas, particularly new ideas that challenge the orthodoxy that runs the place. I think that’s possible. But it’s rare.

So you have a kind of corporatism in the tech art scene, which weeds out critical work.

Even outside of that space, you have the bias of who is excited enough about a technology to begin with. Too many artists working with these tools seem to have a deep emotional commitment to the companies that make them. I see lots of artists — online more than in person — react to criticisms of the technology by taking personally defensive positions.

I would counter that almost every tool has its problems. For me, art is a way of surfacing and discussing those problems. But I see a lot of people resist criticism, or their own impulse toward critique, when I think it could make their work richer. So there’s a kind of emotional entanglement with these systems that can block deep critical thinking about how they work — and who they work for.

Art can sell systems of power,

Art can support technocracy.

It would be wonderful to pretend AI was the world’s first pure technology, without any harms or effects aside from bountiful access to creativity and play, to see it as a “collaboration with an Other intelligence” that “unlocks the imagination.”

Imagination comes up a lot with AI, and I think this points to a historical perspective on AI. Older artists, often established artists, who found AI a potent site for imagination decades ago, had the benefit of AI being speculative. At that point, speculation was an imaginative philosophical exercise, rather than a political one.

AI is a marketing term for big data analytics, but it seems to have a real hold on a certain generation of artists who see it as a manifestation of some vague Silicon Valley promise from the late 1970s.

I have mentioned before how frustrating it can be when we are working with people on present-day harms of AI and get sidetracked into a discussion of “rogue AIs” and “terminators” and the like. I feel like AI art does a similar thing: focuses people on hypotheticals and philosophical abstractions when the real thing is already shaping our world.

That is to say, there’s a certain kind of AI art that is just never going to get me very excited, and that’s fine.

Lots of these are folks with educations and institutional backing that have a deeply researched philosophical position. In the song, I name drop one guy — an award-winning digital artist and writer who has produced art and books since the 1990s. He’s a professor of distinction at a major US university. I am sure many of you love the guy. I’m also sure he can handle some criticism.

When I asked that guy, on Twitter, whether we would be better suited to look at AI with a critical lens as a tool of corporate power rather than his frame — that AI was “collaborative kin designed to spur deep research into what it means to be creative across the human-nonhuman spectrum,” — he responded that my question was “a very predictable critical framework” that I “have been trained to output, one that appeals to humans, especially those seeking validation in the marketable media studies / AI ethics field.”

I think about this a lot. If critiquing AI’s corporate origins can be dismissed as lacking imagination, then I don’t know what imagination is meant to be doing. But it is true: I could never imagine treating Microsoft products as my children.

When work sidesteps meaningful critiques of data & surveillance capitalism in order to focus on statements about AI being “our children” or “our kin,” I can’t read it as a serious engagement with the technology. I think this is a fundamentally flawed frame for looking at exploitative technologies.

People can have those positions, of course. But I don’t see it as building any kind of solidarity. I’ve thought about it a lot after some digital artists unfollowed me when I stormed off of a livestream with a digital artist after he told me violence against trans people “wasn’t real violence.” It’s all very different events, obviously, and I don’t want to conflate them. Another net artist I long admired also started spouting absolutely batshit anti-trans conspiracy theories at me.

If I had any sense that technological art was inherently about care, or protecting vulnerable people from regimes of technological ordering and surveillance, it’s very clear to me that it isn’t.

It left me sort of bewildered at myself for ever believing that the goal of this kind of art was specifically to have effects on technology. In hindsight, I think art in this genre should primarily be seen as a tool for propping up technocratic power.

Which is why I am turning to my own complicity in this space as an artist. Because the only way out of it is not to make it at all. But I’m not going to stop working in this way, with these tools. And I am certainly not alone.

So how do I make sense of my own work? Or the work of anyone of the many good people working with tech who are challenging the ways tech thinks and makes sense of our world?

Beautiful pictures of control

Art alone changes nothing

We, alone, can change nothing.

At the start of the Ars Electronica video there’s a repurposed clip from a Boston Dynamics viral video, where the robots are dancing — originally, to “Do You Love Me?” It’s repurposed here. I came across that clip because of Sydney Skybetter, who has produced a brilliant analysis of his own role as the artist in residence at Boston Dynamics (he had nothing to do with that clip).

I don’t want to put words into anyone’s mouth, so you can go read the transcript of a podcast he’s done where he talks to Anna Watkins Fisher, or listen to it. Watkins Fisher is the author of “The Play in the System: The Art of Parasitical Resistance,” and much of the work cited in the book is that of artists working with and through technology in order to challenge frames, ideologies, and deployments of tech. A lot of it is internet art.

Artists, whether invited or univited guests into corporate tech spaces, have very little power. They are parasites in the sense of the original definition: “one who eats beside.” Artists are invited to these tables because they can see something different, propose a different way of looking at things.

I find it both accurate and humbling to think of AI not as my child or kin, but as a host. And then to think of myself as a parasite, getting underneath the skin of its data. This is also, I acknowledge, a very edgy use of language. But it’s not meant to be melodramatic, it’s meant to be a metaphor for a particular kind of strategy: to invade and divert resources from powerful systems that we are being embedded into whether we like it or not.

Whenever we work with and against technology, there’s a risk of accidentally building a platform for showing off how cool it is, how many tricks it can do. If we resist those tricks, the work is less compelling. So we might opt to leech off of them.

Notably, not everyone has the privilege of being parasitical to tech. My education, and the background that got me that education, plays a role in being able to sit at certain tables, and being able to discern the mechanisms through which these platforms order us.

Watkins Fisher starts the book with this, by Nathan Martin, from 2002, and I am struck by how much it speaks to the post-2020 media arts / AI art landscape:

“The tactics of appropriation have been co-opted. Illegal action has become advertisement. Protest has become cliche. Revolt has become passe. Having accepted these failures to some degree, we can now attempt to define a parasitic tactical response. We need to invent a practice that allows invisible subversion. We need to feed and grow inside existing communication systems while contributing nothing to their survival; we need to become parasites.”

The uneasy conclusion I’ve come through in reading this book is that it’s all uneasy conclusions. If you situate yourself in the heart of tensions, you are going to be tense. My tension as an artist is nothing compared to those whom this technology actively excludes and discriminates against. There is always going to be a lack of moral clarity.

This comes especially as I am in the midst of a community of folks aiming for AI justice, rigorous ethics, and a desire to minimize harm: folks who stand outside of the arts community. An art group I’d spoken to a few times announced, out of the blue, that it was “against AI ethics” on the same week that a venture capitalist published a “techno-optimist manifesto” that claimed AI ethics were responsible for any deaths that AI might have prevented if we weren’t slowing it down.

It seems like AI and art is making everyone go absolutely mad. I have far more respect for the folks who tell me I shouldn’t touch this stuff. My definition of “resistance” is likely greatly at odds with theirs, and I understand the skepticism toward “critical AI art” from, say, a human rights expert.

I’m more aligned with them than the folks who tell me that there’s really no problem at all. So if I do touch AI tools, I feel it’s important to touch them toward revealing their problems, rather than “expanding the imagination” in ways that erase their problems. I want to make work that surfaces these tensions, and if folks are upset with me for it then I suppose that’s just what tension does to people.

Because my goal isn’t only to make art. It’s to connect to other people and to figure out what we might do differently, together.

I think of art as a tool for investigation, rather than a consequence of productivity. It is not art alone that gets any of us where we need to be. That requires solidarity — not with other digital artists, but with people who are not in a position to engage with technology in the way that artists can.