Where Does the World Happen?

A Conversation with Artist & Researcher Rūta Žemčugovaitė

Rūta Žemčugovaitė is an artist and researcher living in Berlin. Her work is a study in mycelium for regenerative futures, infused with experiences in trauma healing, systems thinking, and regenerative practices. We had a conversation about mushrooms, post-human systems design, extractive capitalism and what lays beyond.

If you are in Berlin, you can participate in Rūta’s December world-Building workshop with Niels Devisscher, aimed at moving from “designing for humans to designing with all living beings.” You can also read her Regenerative Transmissions on Substack.

We started off by talking about Worlding: Sympoietic Mycology, an album made by extending the communication network of an oyster mushroom into an analog synthesizer. From there we moved quickly to the idea of recursion: how individual pieces of a system, placed together, form relationships, which form systems, which form new relationships, which form new systems, etc., with regression being a way to think about those relationships and what they produce.

This conversation was held over Zoom and has been edited for length and clarity.

Where the Worlding Happens

Rūta: I was looking at your post on mushrooms and mycelium recordings, and talking about layers of regression that we can go back into by asking: “What is the essence, what is the essence, what is the essence?” We could define that as post-apocalyptic. We could define it as a completely new reality that is emerging from wherever we want to put our reference point: a recursion into the essence of relationality.

Redefining relationships to the rest of existence is at the center of survival and going forward. There is no other way around. The time ticker for the narcissistic bubble of humanity is ticking. It’s being induced by all these events that are happening right now, and it’s disintegrating. It’s almost like a birth. You can’t do anything to prevent it. It’s happening and you have to just go with it, and you have to completely refocus your understanding of yourself and the relationship to everything else in the world.

Today we put out another event on worldbuilding in December in Berlin. We’re going to go deeper into pulling creative people, artists, writers, storytellers, anyone interested in that kind of change making. To not just imagine what this multi-species perception might look like but also take inspired and aligned action with it. This is where that is centered.

I’m curious, when you talk about Worlding and world-building, what is that for you? What does that look like? Because from a narrative, traditional story point of view, world building has very defined ways to create a world, from science fiction for example. What does it look like in this reality for you?

Eryk: Because I teach video game design, I think of world building kind of concretely. But I teach video game design through my background in cybernetics - a systems, relational approach. So I am always trying to bring this into video games, where there is typically an object and another object and a goal and usually a conflict, and play is what emerges from those relationships.

I think of worlding a little differently. Regression and recursion play a part, too. If I look at something this close or that far, my relationship with it is different. There are other things that become part of that wider or closer view. You can think about the mushroom, and you can think about the synthesizer, but you can also think about a mushroom connected to a synthesizer, and you can also think about the patch cords that connect them. If you think about the connections, you start seeing the actual world that is there. A world isn’t just the mushroom and the synthesizer and the headphones but is the stuff flowing through and between them. The electrification of relationships!

Which is not what it always is, but here, mycelial networks have these entanglements with plants and trees and water and even dead materials that they can break down to feed the trees or plants. It’s those relationships that I think of as the Worlding.

Rūta: So it’s almost like this emergent place-making within the space between things, between the subjects. The emergent quality of that.

Shifting Shape, Shifting Scale

Eryk: That’s where the Worlding happens. That’s where the world becomes built up. The mushroom and the synthesizer are discrete, they are their own systems, but through that entanglement they create a relationship, which creates a whole system of flows and movement that could be described as a world. And I am doing something with it, spraying it with mist, resting my hand on it. So, there are other aspects that come into the relationship. That world keeps growing larger the more we move out. To think through what I saw in your writing, the shapeshifting — I think about that as scale shifting, too... it seems to resonate.

Rūta: It absolutely resonates! The connection is establishing a new relationship, and from that relationship a world is born. It’s planting the possibility of things to happen there, in that space–time, reality, and you can keep expanding it by adding variables such as hand, light, temperature, mist. I want to ask though what do you mean by “scale?”

Eryk: I did a master’s in Applied Cybernetics, and they kept talking about scale. And honestly, I had come from San Francisco, and all scale ever meant there was, “you’ve got to bring your startup to scale.” Scale meant it’s got to grow, grow until it pops. That understanding set me back because it never occurred to me that there are so many other forms of scale. What we were talking about was more like zooming in and out with a camera, or slowing down or speeding up time with a tape recorder, or placing ourselves in some new position with relationship to what we were looking at. There are emotional scales. Our closeness or distance to something is limiting what we can see, but it’s also changing the relationship to what we see. And understanding that can be useful.

You can get very close to the mushroom, right into the mycelial network. You can go into the fibers and the electricity flowing through them. You could zoom out more and see that electricity flowing through the patch cord. You can go into the patch cord and see, ok, what’s happening here? And the synthesizer structure, and now you have a bigger system, and you can go into the synthesizer. Or you can see the system as a thing, and think about its relationships with other things, other systems. And you can reveal or discover so many different things by thinking about it in a closer capacity. Have you read Tyson Yunkaporta?

Rūta: Yeah I was in a Kinship learning journey with him.

Eryk: Oh wow! The way he writes about scale in Sand Talk, there’s this yarn about the hands and how each finger represents a kind of lens. So the ant view looks up at a daisy, but you can combine this with scales of time, so that you can look through the lens of kinship, for example. And you can connect these fingers, so that you connect the scale of time and relationships to the ant view. And these are different combinations of scale to look through. It had never occurred to me that this is what scale could mean, because I’d spent too much time in Silicon Valley, I got startup poisoned. But now it’s how I think about it…

Rūta: Scale of perception. Moving through embodiments of different perspectives: zooming in and out. These sayings like ‘the bird’s eye view,’ we know that we have to zoom out…

Eryk: Right, and that’s scale, but you use this phrase, shape shifting, which connects…

Rūta: With shape shifting, you are trying to move as close as possible into the perspective of the other being, of the other species, so you can try to grasp what it means to be that other being. Suddenly you realize, “I just reduced this other being to this mushroom, or this ant,” but once I’m submerging myself willingly, consciously into the experience, even through my imagination, I realize there is a whole community I belong to, a whole ecosystem I belong to. There is past and present. How do I carry memory as this being in this landscape? What we were thinking, also, to do in the workshop is really present this moment, or future, as just a collection of experiences of beings that are experiencing that future. What if we took this very zoomed in experience of all these living beings and we mapped out a future of these experiences? And find connections through there, rather than saying ‘this is the future we need to build, this is what we’re going to do.’ It’s a bit of reverse engineering: ‘what will be the best experiences?’

Of course, it’s very challenging. We’re listening to Andreas Weber, mentioning that we’re falling into this trap of trying not to anthropomorphize anything. It’s like a cancel culture: ‘You anthropomorphize everything!’ But it’s in a way impossible because we are human and we are incarnating as a human being. You cannot fully detach from this lens. Nor would you want to fully detach from this experience. Because that’s where you are. That’s the body you can experience this world through.

It’s the same way with myths. There are so many beings and plants and animals that are talking through human voices. We could say they’re anthropomorphized but it’s also the human psyche trying to make sense of the world. Maybe it’s externalizing the psyche and projecting it fully onto the world. It’s saying, ‘the horse is saying this, the seal is saying this, the mountain is talking.’ But maybe at the same time we can hear those beings. It’s just that, the filter is the human consciousness. We’re receiving everything. The world is always talking to you, the world is always trying to communicate, I believe. It just depends how wide our perception is.

So I think shapeshifting, especially in this modernized way of doing it, can be a way of shifting that relationality.

Synthesizers and Extraction Capitalism

Rūta: What Tyson Yunkaporta was saying, and maybe it’s a different context, but even now with the way capitalism works, it also finds every single opportunity to extract... even a campaign of regeneration, or interbeing. Capitalism, it flips it over and says ‘ok this is where the interest is going, we’re going to infiltrate this thing that seems still quite light and new and prosperous, and we’re going to turn it into something that can be extracted’. So I am also interested — and maybe it’s a quick transition — to the extractive nature of economy, the extractive consciousness that we are operating in. So how can we move from extractive consciousness into this interbeing? I think it’s through that switch of relating and relationships.

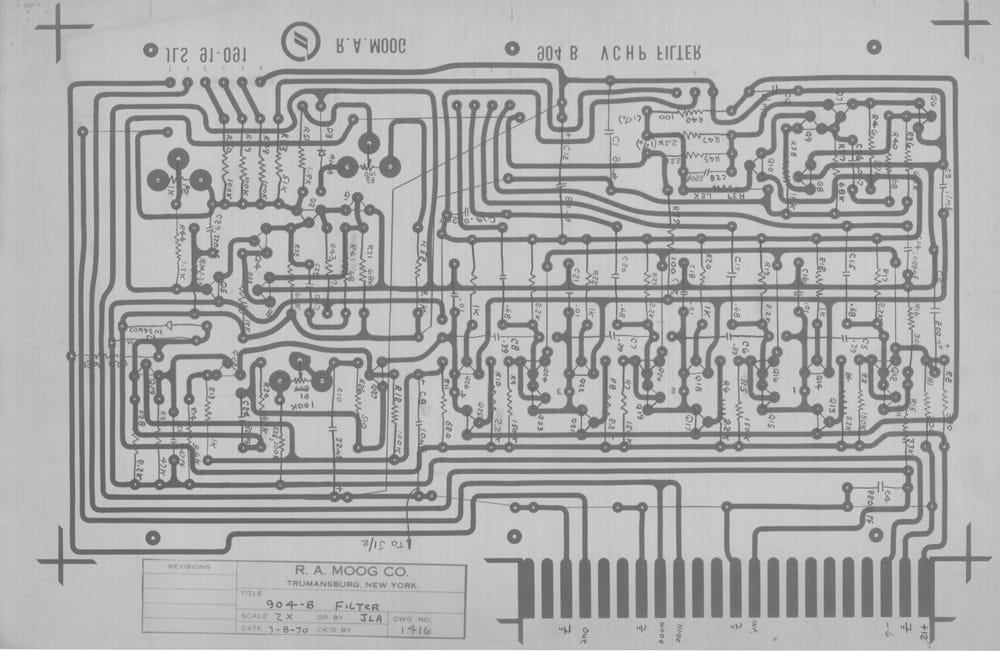

Eryk: Thinking about this connection between relationships and extraction, I am thinking about the synthesizer as a stand-in for computational logic, information processing logic. The synthesizer is a machine, an analog computer in some sense, taking electrical information and processing it. I wonder if this relationship and shape shifting extends to the synthesizer? This is a big dilemma for me.

Rūta: My friend Bridget Walsh would have a lot of things to say about it. She’s been working with synthesizers for quite a while and studying acupuncture. Really looking through that perspective — and I think about it quite often, the question of technology, it’s almost like an extension of human consciousness made into something else. With synthesizers, especially the analog, you’re working with all these circuits and redirecting them. Personally, I feel the sound of an analog synthesizer on my nervous system differently than a digital one. It feels deeply grounding. I don’t know why. But you can almost feel the current going, and the way our bodies work, you can say from the Eastern tradition, our meridians are going and you’re unlocking knobs within your body through acupuncture or movement or any other body work that can allow those movements and different circuits to unlock. So I see it from that perspective. What do you think?

Eryk: I made music on laptops for years, and only for this project did I move to an analog synthesizer. It was important to me because the concept is this electric flow. And what I have learned from analog synthesizers is that we claim to control them, but they are very — finicky. They’re particular. You touch a knob quickly with a light touch and the sound transforms, because the electrical flow has been radically altered. The way they work through the storage and stretching on the electrical level, what you’re doing is so strange and uncontrollable even in highly sophisticated components. Circuitry produces a worlding of its own, maybe without sentience, you know, it doesn’t have the same kind of perception as a mushroom. But it’s the flow of electricity, and the electricity is also the organizing flow of the mycelial network. So there’s a relationship.

But the flip side of that question is that, as a technology, the extraction is still happening. It’s taking a mushroom’s internal communication flow, and moving it into a human built system to create something that we can hear or enjoy. And this is a tension for me. It’s a matter of scale, too: I’m putting music out there as a product. People can buy it. And look, I don’t have real moral qualms about that. But the philosophical experiment raises questions for me. Is the synthesizer, as a metaphor for other technological instruments, essentially extractive? Or is the synthesizer in a real exchange? Is it something that depends on the position and reference point toward that system and what is emerging from them? That was a bit of a ramble!

Rūta: Not a ramble! I think this is where the majority of work lies, in understanding that. Because the world is by its own core nature, its core essence, deeply interactive. There’s no way you can stop interactivity with the world. From particles, on the smallest scale of waveform vibrations, to huge bodies colliding and affecting each other in gravity. We cannot prevent that interactivity. But we can also create points of interactivity, like putting a synthesizer onto a mushroom and trying to understand ... ‘What does it do? I’m curious.’ And you’re led by this curiosity. Your motive is not to take the genius of the mushroom and make so much money and destroy all species of mushroom to keep one strain that produces the best electric channels! So you’re going at it from a very different perspective.

People who are very concerned with ethics of relating... we still need an ability to see that interactivity and not be afraid of it. Sometimes it’s like you can’t even walk on the grass because you might squish something there! It’s kind of inevitable. Myself, growing mycelium in the lab, I’m so far away from it that it doesn’t feel right to me. Even if it’s a studio lab run by a community, and we’re all building together. So I brought the mycelium home temporarily. Now I can just observe how it’s growing, and it gives me so much joy to see that it's growing every few days, getting bigger. And looking at experiments with hemp, trying to scale it and realizing it’s really hard to scale these kinds of things. So that’s another challenge for me too.

I’m building a sculpture to talk about extractivism and this new wave of capitalism coming in, that’s going to be harder and harder to decipher and see for what it is...

Eryk: Which capitalism? What strand?

Rūta: It’s shape-shifting all the time. I’m seeing all these mycelium, mycofabrication companies rising and there’s so much support and excitement. And I’m also excited for them! I had a chance to talk to Merlin Sheldrake, who wrote The Entangled Life, about this new branch of mycology and fabrication. Are we just transferring the same extractive consciousness onto something so sacred? Or is there still room for reverence and respect, a chance to change our relationality before it’s too late. Before we’ve given it over to the inertia of capitalism. He said there’s definitely space for redefining that relationship. I think it’s a matter of talking about it, and maybe doing that Worlding that we’re doing now in our conversation about it can create a new perspective. We don’t want mycelium or mushrooms or fungi to “save” the Earth. We can’t just place it on one being to do all of this work.

Part of my work comes from my background in psychology and trauma healing, too. So I still want to involve that in art somehow. It always comes back to looking at the part of ourselves and the part of our psyche that are marginalized in some way. Part of it is looking at the refusal to heal, and when we look at our current society and economic system, there’s this whole notion of fixing yourself, and productivity, and self-help and healing. I want to look at the parts of ourselves that will not heal into a society that will not change its extractive nature. It masks maladaptation as a healing. Mycelium in this project is this alienated body, an alienated part of the human psyche that pulls a brake that says: I will not adapt into the current game.

The Underconscious

Rūta: If you understand the human psyche, the preliminary conscious / subconscious mind, many of the things we feel cannot exist in this society are the parts of ourselves that are not productive, not social-izable. That is not fitting into the confines of the system that there is. Seeing it as a manifestation within the body, as chronic illness, as neurological development–a being or a nervous system that you cannot socialize into this common dream we’re dreaming as a society. So, looking at the parts of ourselves that do not fit into this spectrum of a society, we kind of have to push them away, bury it underground into our subconscious.

If we look at the ground as a subconscious mind, mycelium is underground. I’m looking at it as a parable — if we externalize mycelium into a 3D shape that we can see and interact with, we can say: OK, I’ve externalized a piece of the human subconscious, an alienated piece that I can look at, and acquaint myself with it in the light, the daylight of consciousness. It’s working with that idea, addressing the refusal to fully come into this society. If I fully heal, if I fully reveal myself, I will be extracted from again. I’ll be in the same cycles of this economy, or this consciousness that operates not through relationality, but through extraction.

That part of ourselves or our collective unconscious really holds a lot of truth about what we can learn from. Maybe the healing happens when we make the change in the surroundings, and don’t blame that part of ourselves anymore. Maybe the rest needs to shapeshift around it.

Thank you for reading! If you enjoyed it I hope you’ll consider sharing this post (on social media or by email). Likewise, if someone shared it with you, you can subscribe or follow Cybernetic Forests in all kinds of / too many ways!