Radicalized by the Game Genie

Machinima, AI Art and Frenzied Euphoria of Broken Code

The earliest influence on my approach to artmaking was probably an off-brand accessory for the Nintendo Entertainment System: Galoob’s Game Genie. As a child of the ‘80s, discovering the mysteries of the world, I made sense of its rules and structures through the images on television screens. I entered into a game world, with limits and boundaries to what I could do: a safe space to play along on stage with a game designer’s imagination, referencing it with the world outside.

The Game Genie was a daycare jail break. It was anarchism. It was 8-bit LSD.

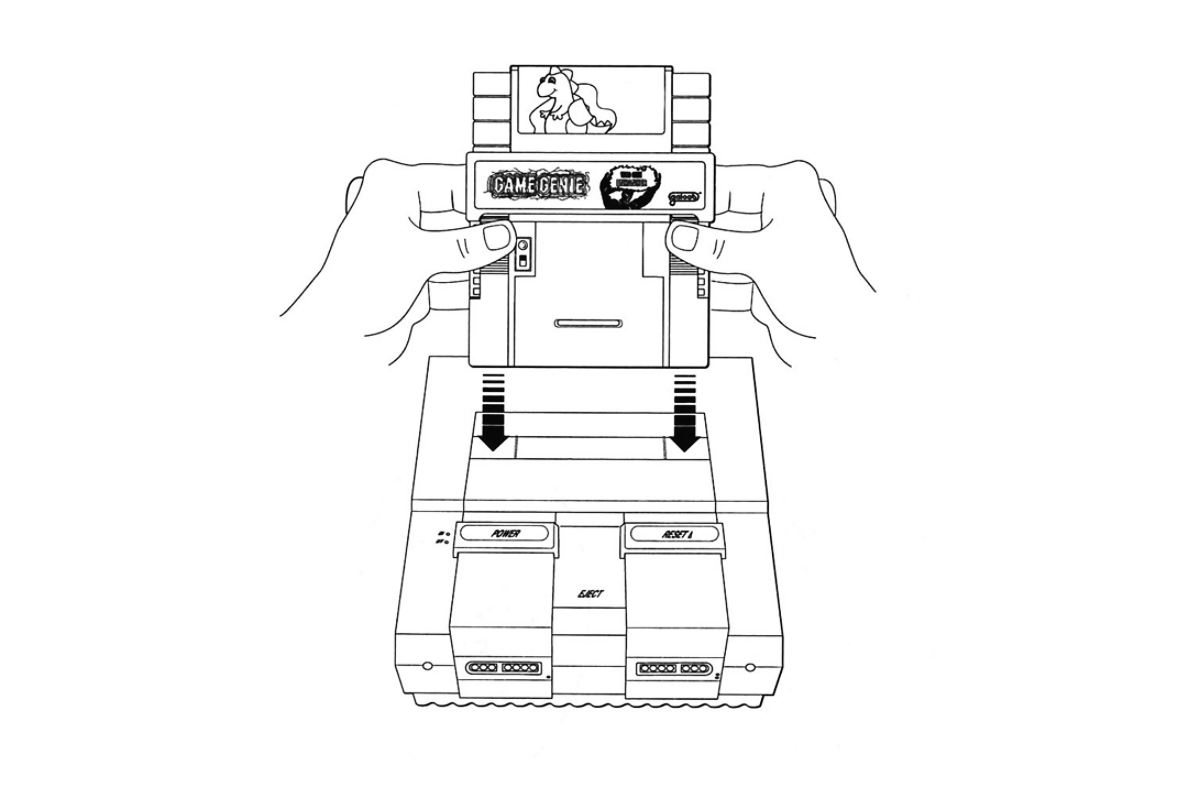

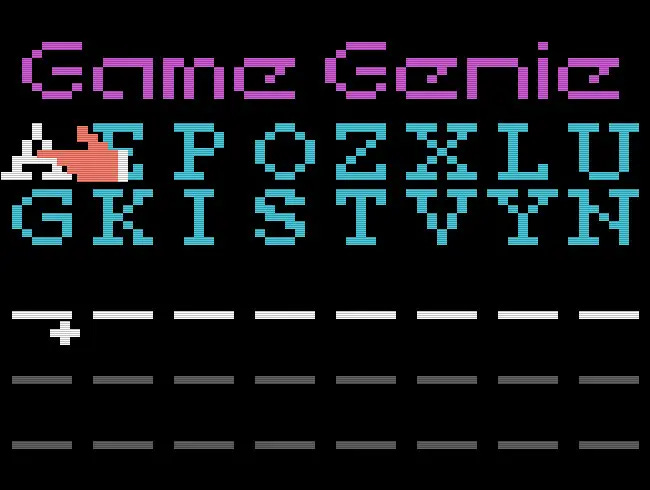

The Game Genie was a plastic intermediary between your game cartridge and the Nintendo console. The Genie inserted code into your games and transformed the rules. You entered codes into a prompt on the loading screen, and your game was played through whatever you just injected into the code. Some of these effects were unnoticeable, others made games unusable. The best ones came in code books; the rest, you tested on your own.

The Game Genie injected some of that code straight into my psyche. To this day, when I dream of flying, I fly the way the Game Genie told me I could fly. Super Mario jumps, then jumps on top of that jump, upward forever, never landing. The Game Genie could hack the code of gravity.

Game Genie suggested that the invisible codes that ran software and society were malleable. It introduced me to hacking: not only computer terminals but social codes, contributing to a period of juvenile delinquency full of art crimes. It undermined algorithmic authority early. Alongside it, authority writ large was writ smaller.

I have been teaching, reading, writing, and playing video games for a master’s level course on Disco Elysium, storytelling and game design at Bradley University and teaching introductory game development / interactive media classes for undergraduates at RIT. I like games. I like thinking about games. I think about games as systems: stories co-created through relationships with machines and our complicated, permeable, and trusting imaginations.

Games tell, and reflect, stories. They move people. They allow for immersive, imaginative reprieves, a cinema with agency. But people design games, just as they design software. In one of the essays I read with students, Greg Costikyan unpacks his definition of what a game is.

Games have interaction, he writes. That’s obvious. But games have interaction for a purpose: the goal. The player reaches goals through the gaming system's rules, called mechanics. Developers create these mechanics to set the stage for play. They often introduce some element of struggle.

Costikyan’s most interesting piece of the definition is a quote from Eric Zimmerman: "games are structures of desire." The rules assembled into a game provide us with our goals and tell us how we’ll achieve those goals. We enter into and accept that structure. Then, we have a bounded space in which to play.

[G]ames have goals, and players mutually agree to behave as if the goal is important to them when they play – the game creates a desire to achieve the game’s own goals. By structure, [Zimmerman] means that the interaction of the game’s rules, components, software, etc. create a structure within which people play. … Game structure has to do with the means by which a game shapes player behavior. But a game shapes player behavior; it does not determine it. Indeed, a good game provides considerable freedom for the player to experiment with alternate strategies and approaches; a game structure is multi-dimensional, because it allows players to take many possible paths through the “game space.”

I’ve been applying different lenses to AI art lately: AI art as visual poetry. AI art as chance art and performance event scores, AI art as photography, AI art as craft, AI art as improv comedy. So let’s add one more: AI art as video game.

Art Games

SimCity 4 is an interactive and dynamic canvas that we can use to build personally expressive cities. Photoshop was a space that offered an interactive and dynamic canvas, too. Intuitively, we might see someone’s work in Photoshop as more creative than the cities they make in SimCity 4.

There are some good reasons for this. SimCity 4 limits you to certain tools and structures. But then, so does Photoshop: your landscape is the canvas, the structures are the pen tips and brushes. SimCity 4 activates your images in specific ways: once drawn, they begin to interact with other elements. That’s missing from Photoshop.

SimCity has mechanics that transform its underlying structures in ways that can be steered, but not directly controlled, by the player. These mechanics are based on an early experiment in artificial intelligence: cellular automata.

The cities we build within SimCity 4’s structure are constrained by those structures. To be a truly expressive medium, we would need to use it in ways that tell our own stories: to structure our own desires. This is where we see boundaries between SimCity and Photoshop: in one, structures are imposed more heavily than the other.

What if DALLE2 is not strictly an art-making tool like Photoshop, but an art-making Sim, a game engine for art making? DALLE2 encourages creative expression within the rules and structures of its mechanics. This is how game narratives are co-created: imagination enters into a mutually created space, and players interact with that world which the code renders to reach some game-stated goal. In the art game, the goal is the creation of a suitable image, rather than slaying a dragon or building the city of our dreams.

Video games create systems that shape the way we play them. AI art interfaces create structures that allow us to play. These interfaces offer genuine delight and curiosity. But like video games, this delight and curiosity is bounded by invisible mechanics, which ultimately shape the desires that we bring into them. In video games, if we know we can ride a horse or pet a dog, we may endeavor to do that. If only certain creative goals are possible, we will cater our own creative goals to what the machine can accommodate.

DALLE2, rather than an AI image generation tool, might be better described as a creative-game engine. A creative-game is one where the player’s goal is to create. DALLE2 players are bounded by sets of rules. We have to engage with those rules in order to get our desired images out of its mechanics.

One of those rules is: enter a prompt, select one of four images. The game will take a prompt and turn it into four images. To continue the game, you choose one. Then you can use it to create another. That’s a game mechanic.

Which is not a bad thing.

In fact, play is my ideal philosophical framework for making art. It’s only the strange desire for AI artists to be met with traditional (i.e., very conservative) definitions of artistic merit that make this sound like I’m reducing the experience to making and admiring these outputs. But many AI artists, especially “promptists,” seem to be in a double bind. On the one hand, they claim AI art is a revolutionary new medium that more people should understand. On the other hand, for years now, this claim to revolutionary potential has been backed up by showing how well AI can reproduce landscapes or portraits from public domain archive collections.

You can’t prove a medium’s originality by showing how well it imitates past forms.

I say: embrace AI art as a new way of making art. Embrace it as gameplay. Embrace the delight of it. But also, let’s draw boundaries that protect us from image generation as spectacle. Let’s embrace these outputs as a source of further play, not the end point.

We could say that the tools set the rules for the art-games people play. But an artist gets to tell the system: Here’s a new game we’re playing. They get to invent new rules. They get to add new tools. The question becomes more interesting: how we do move our relationship, as artists using DALLE2, away from consuming its choices, and into producing work — to steer this relationship away from machine dominance and toward our own desires?

In other words: how do we begin to make our own games, rather than playing somebody else’s?

Super Mario Movie

One way artists answered the video-game-as-medium call, more than two decades ago, was through a new genre of storytelling, machinima, a portmanteau of “Machines” and “Cinema.”

Diary of a Camper (1996) is considered to be one of the earliest examples of this genre. It requires some significant orientation to Quake’s interface and mechanics to make sense of any of it. And, through the lens of today’s Twitch streams and endless game play videos, it looks like any other group of players hanging out.

But the video used the mechanics of Quake to create and act out a scripted performance. The skit is basically a meme, but it opened up creative possibilities for gaming to tell different forms of stories, using a new visual language. Those stories broke the rules of the game engine, appropriated visual and audio elements, remixed, rehashed, or broke the code altogether.

Here’s another example. In 2005, Cory Arcangel went into the code of a Super Mario Brothers cartridge and changed it, using the game’s assets to make a “film”. The entirety of what you see below is through hacking an actual game cartridge in strategic ways. Mario, trapped in a disintegrating Super Mario Brothers cartridge, is contemplating his fate.

Cory Arcangel’s work reminds me of the Game Genie for more than one reason.

First, it’s about taking control of the codes meant to create structures for how we engage with a piece of software. It bends that structure to do what we want it to do, and turns into a struggle between “players” — the code and the person bending it. Second, it takes the form given to us as players and repurposes it into something “new.”

Machinima was a way — like modding — to “restructure our desires.” Artists extracted meaning from the imposed structures of games and rearticulated them. There is always a navigation of the existing code, but new potentials resulted from the bending.

The most exciting possibilities for creating AI art are not in the nuance or fascinating minutiae of prompt engineering. The potential of AI art is yet to be realized. It will come about as artists learn to pull away from the call-and-response of the prompt window and its prizes.

When I make AI art on DALLE2, I feel more like the player of a game: making informed guesses, struggling to steer the machine to certain outcomes. The images that DALLE2 produces are the results of combining interesting, pre-existing semantic relationships in its vast dataset, by exploring the model’s latent space. But the model shapes our desires: it offers us options to choose from and build off of.

As the lines between productivity and creativity come closer together, we need to protect and exercise our agency over the tools that deliver content to us and call it personal expression. Not because we need to appease some academic, institutional definition of an artworld that is slow to adapt to new mediums. It’s critical because historically, technology hides its seduction in the blurred lines between generating and consuming content.

Social media lures us to create for the sake of social affirmation. In exchange, we consume those likes and comments. We do this within a “structure of desire” — not a game at all, in the case of social media, but a hijacking of social instincts. Our relationship to these technologies can be swayed if we — dare I say it — embody the spirit of the Game Genie. That means embracing art as a critical intervention between players and code — encouraging experimentation, rule-breaking, and even slight swings of the pendulum from passivity toward human agency and imaginative play.

Out of the Bottle

When we defend tools like DALLE2 as if the raw product is an artistic expression of the one who types the prompt, we sacrifice some of that criticality in negotiating the lines between personal expression and technologically mediated desire. The prompt is an idea, but the image — the expression of that idea — is left to the machine. When AI artists claim that other artists navigate these relationships, they’re correct. But the most innovative and radical art is made by artists questioning and interrogating that relationship.

When we make AI art from a prompt, we are searching for ideal recommendations from the structure. Suggestions, culled from data, of what our dreams might look like.

How you play the game of AI art is a decision you get to make. You can abide by its structure of desire, or you can follow your own. You can question and interrogate your relationship to your tools. You can bend the rules of the game you’re being asked to play.

Play, and art, are equally valid assessments of AI art-making, neither of which undermines its potential. But we should always be cautious of technologies that mediate and shape the possibility of our imagination into predetermined forms.

Cybernetic Forests is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.